Executed folk singer Victor Jara’s song “El derecho de vivir en paz” (the right to live in peace) has become the anthem for the rebellion unfolding in Chile. Written in 1971 as a tribute to the struggle of the Vietnamese people, it became a popular song of the Chilean workers’ movement, which at the time had high expectations and aspirations to build a new country under workers’ control after the election of the socialist government of Salvador Allende in 1970.

I was born in Chile the year Allende came to office, and my family fled the country in 1975, two years after the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet took power in a coup. While I have no memories of those years, my entire life has been shaped by those events. During my childhood and early adulthood, my parents would go through in detail not only what they experienced but also what thousands of others experience during those times.

Mum and Dad spent countless hours telling me and my brothers and sister the history of Chile and the struggle that had taken place. They spoke of their aspirations – and those of millions of others – to build a socialist society and their willingness to fight for it. They spoke of the struggle under Pinochet, of the disappearances, torture and repression that so many faced. Many of my family were forced to flee the country to all the corners of the world (Australia, Cuba, France, Sweden). My story is not unique; it happened to millions of others. The brutal dictatorship that overthrew Allende not only got rid of a government and a dream of a new Chile but also repressed and destroyed an entire generation.

Now, Chile is finally shaking off that legacy. The slogan of the new movement – Chile despertó (Chile has awoken) – indicates that the people are aware of the history but will no longer be silent. The movement, sparked by high school students campaigning against a metro fare rise, has spread across all generations and is once again demanding what was hoped for and dreamt of in the late 1960s.

It is no coincidence that many of the songs from the late ’60s and the Allende period are again sung at every mobilisation. This movement is not about reform but about taking back what was brutally repressed in 1973. The protests have re-inspired an entire population to begin the process of building a country run by the people, not the billionaires and international capital. The hope of a new Chile, crushed by Pinochet’s dictatorship, is blossoming once again.

The explosiveness of the mobilisations has startled and unnerved many liberal commentators. It is for this reason that very little has been said about Chile in the mainstream press. The unfolding struggle is not only the most significant to hit Chile in several generations; it is also significant for the rest of Latin America – and the world. “The fact that protests are roiling one of Latin America’s most prosperous nations suggest a similar situation could easily happen elsewhere”, Bloomberg senior editor John Authers wrote on 22 October:

“Outside the country, Chile has been seen as the living embodiment of the economic policies installed under Pinochet by the ‘Chicago Boys’ – a group of economists, many of whom had been trained in free-market ideas at the University of Chicago. Chile’s pension reform, in which everyone must pay into private pension plans overseen by the state, was used as a template by countries around the region, and has allowed a steady buildup of patient local capital. Meanwhile, globalization allowed Chile to benefit from its huge supplies of copper. In relative terms, its success is undeniable. In 1975, just after Pinochet had taken over power, Chilean gross domestic product per capita lagged Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and even its neighbor Peru. Now, it has more wealth per capita than any of them. It has avoided the crises that bedevilled the rest of the region.”

The liberals and the right have for decades held up Chile as Latin America’s success story, using it as an example of what nations could do to drag themselves from poverty. It has been used to highlight the “benefits” of privatisation and the opening of national markets to international capital. What is always ignored is that the “Chilean Oasis” is built on 17 years of military dictatorship, brutal repression and an economic and social system that excludes the majority from gaining any benefits. Chile is one of Latin America’s wealthiest countries, but also one of its most unequal.

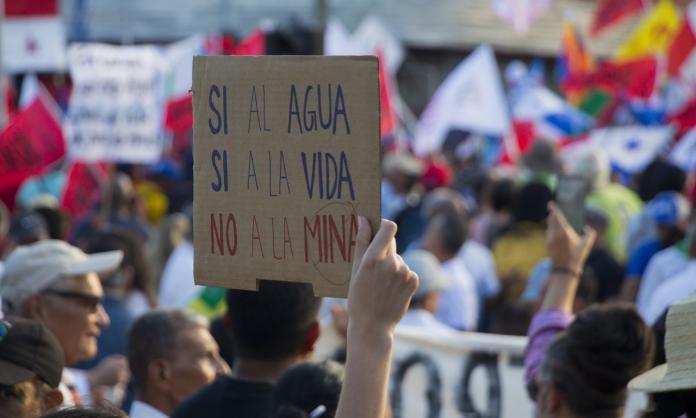

But things have begun to change dramatically. A popular slogan is “No son 30 pesos, son 30 años” (it is not about 30 pesos but about 30 years), referring to the period since the collapse of Pinochet and the country’s long experience of neoliberal policies. This is clearly not just about reforms but a fundamental change in the political, social and economic system. It is an unfolding revolution. Reflecting the cross-generational dynamic of the current uprising, among thousands of placards that have appeared, one read: “Bourgeoisie, shake in fear, as the children of the workers have come out on the streets”. Another read: “We will not return to normality as normality was the problem” – highlighting that what was considered Chilean democracy was in fact an extremely unequal society carefully guarded by a military force that brutally quelled all social resistance.

Chile is no stranger to mass protest. Throughout the dictatorship, people resisted. After the fall of Pinochet in 1990, Chile experienced a variety of protests by various sectors. More recently, high school and university students have been at the forefront of mobilisations for free education, among other things. But this new movement has radicalised quickly. From initially opposing a metro fare increase (the 30 pesos), it has progressed to the demand for a constituent assembly to rewrite the Chilean constitution, which was drafted under Pinochet in 1980. It is clear that the political, economic and social system based on that constitution has no legitimacy.

Billionaire president Sebastián Piñera continues to say that he is listening to the people and is willing to make changes, but there can be no illusions that the system can be changed from within. The entire structure has been built on repression and privatisation of all services and resources. Much was achieved during the Allende government that helped transform Chile into a much more equal society. However, the limitations of trying to work within the system were also evident. Not only did Allende and thousands of other Chileans pay for it with their lives, but millions also had to endure 17 years of brutal military dictatorship.

Unfortunately, the Communist Party of Chile and the forces within the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) have learnt nothing from those experiences. “The Frente Amplio and the Communist Party are posing as the left at the same time they are agreeing to participate in negotiations with Piñera”, Dauno Tótoro of the Revolutionary Workers Party argued recently in an interview with the website Left Voice. “And they’re also calling for a ‘constitutional accusation’ (a type of impeachment) against Piñera. In other words, they’re trying to subvert the rebellion by channelling it toward a constitutional solution. They want to make the people believe it’s possible to remove Piñera through a parliamentary vote.”

The problem is that such an approach could take steam out of the mass movement. And even if Piñera could be removed, the system that he presides over would remain under whoever were to replace him.