Sunday a week ago, Bolivia experienced a coup orchestrated by the most reactionary forces of the country’s ruling class. The workers of Bolivia will not accept the coup or the rule of those elites who want to reassert their direct, unrestrained dominance in the Bolivian state. What exact power arrangements emerge over the next weeks and months, and the degree to which the political ambitions of these elites can be suppressed, will depend on the ability of the workers’ and social movements to elaborate a political agenda not compromised by the corporatist, social democratic politics of the government that was just overthrown: that of Evo Morales and his political party, the Movement for Socialism, or MAS.

The reactionary violence of the last week bears witness to the words of the French revolutionary Saint Just: Those who make only a half revolution do no more than dig their own graves.

Morales and the MAS rose as a hegemonic national political force on the back of a five-year-long insurrectional wave of popular protest, dating back at least to the Cochabamba Water War of 1999-2000, when the privatisation of a municipal water company led to protests that became a localised uprising. The nationwide, prolonged, very combative struggles against the old neoliberal governments changed the balance of class forces. They drove the ruling class into retreat, drowning out its political voices and creating a political vacuum.

In 2003, the businessman-president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada was ousted after the bitter conflict known as the “gas wars”. Morales was a prominent figure then. By that time, MAS was already consolidated as an electoral option rather than a party of struggle: it channelled the demands of the movement toward a new redistribution of the national wealth rather than a new order. In 2005, Evo Morales was elected first Indigenous president of Bolivia, and MAS gained a majority in the lower house of parliament.

The program of the MAS did not fundamentally challenge capitalist relations. In fact, in many respects it was weak even compared to the sort of bourgeois-democratic reforms familiar to Latin America’s nationalist governments in the first half of the 20th century. The MAS government pursued “shallow” nationalisations basically imposed larger taxation on multinationals in exchange for stability for their investments, which in Bolivia is an especially rare commodity.

Unlike some of the forgotten nationalist reforms of pre-neoliberal times, Morales did not carry out an agrarian reform of any substance or fundamental reforms in areas like education, where resources and opportunity remained the preserve of the private schools for the elite, despite the construction of thousands of new educational centres. The MAS nationalised only some thirty or so companies, most of which had been state-owned before they were privatised by preceding governments.

But in the context of the prolonged neoliberal theft of all of the resources of Latin America, the MAS government’s reforms did provide a contrast. Instead of managing the surplus for the enrichment of the top 10% of the population and further lining imperialist pockets – like in Chile, where in a similar period 80% of annual growth went to this upper middle class – “Andino capitalism”, to use Vice-President Linera’s ideological characterisation, invested in productive sectors that generated income and jobs.

According to a report by the Latin American Strategic Center for Geopolitics, the first MAS administration’s reforms managed to redistribute back into the general Bolivian economy an estimated $74,000 million USD, roughly equivalent to twice the nation’s GDP. Over ten years, the MAS government gained $31.5 billion USD from state interests in mining, oil, energy and other companies, compared to $2.5 billion USD during the previous ten years of neoliberal governments. This surplus was then invested through manufacturing, agriculture, construction, tourism and in the services sector, creating some 670,000 jobs.

Over the first two MAS administrations not only did Bolivia’s growth rate outstrip its much larger neighbours such as Brazil: it also managed the highest international reserves in Latin America, low government debt and inflation, and an over 300% increase in average income.

When I visited Bolivia earlier this year, the transformation compared to our visit in the lead up to the fall of Lozada in the early 2000s was palpable. There are roads where before there were none. Public transport in La Paz is now better than in many much richer countries, and worker and pensioner incomes provide an embarrassing contrast to countries like Argentina and Chile, which previously towered over Bolivia as economic examples.

You could say that the MAS administration saved Bolivian capitalism from itself. But this is exactly the fallacy of social democratic thinking: the idea that capitalism can in any way be meaningfully tamed and brought under control. Contradictions can be suppressed or their consequences redirected but only to re-emerge in other ways and usually – especially in an era of long term decline – with more venom.

The redistribution of income expanded domestic demand and buttressed a middle class otherwise severely short on opportunity. Some 3 million people were lifted from the dire poverty typical of Bolivia throughout its history; extreme poverty went from 38.4% in 2005 to less than 15%, and what is referred to as “moderate” poverty decreased from 61% to 34%. Monthly average wages increased from $60 USD to $310 USD.

This redistribution – while undeniably improving the life of millions – recreated the country’s class contradictions along more modern neoliberal forms. In a way, under the MAS, Bolivia experienced a similar socio-economic “modernisation” as Chile, but in a compressed period of time. This was made possible by the social peace the MAS government achieved, restraining class struggle.

The MAS was always a profoundly rural and peasant-based party – moreso than organisations like Ecuador’s CONAEI, which were more built around an Indigenous identity. It effectively used its social weight, and its potent mix of anti-imperialist and Indigenous rhetoric, to smother and co-opt the voices of the urban (and rural) organisations that had previously been at the vanguard of the workers and campesino (peasant) movements.

Over the last decade and a half, the MAS has channelled popular demands and leaders into parliament and used all sorts of privileges, corrupting policies and intimidation to tame and effectively demobilise organisations such as the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB), the Single Trade Union Confederation of Peasant Workers of Bolivia (CSUTCB), the National Confederation of Indigenous Peasant Women (CNMCIOB), the Indigenous Central of the Bolivian East (CIDOB), the Trade Union Confederation of Intercultural Communities (CSCIB), the National Council of Ayllus and Markas del Qollasuyo (CONAMAQ), as well as many other local and grassroots organisations.

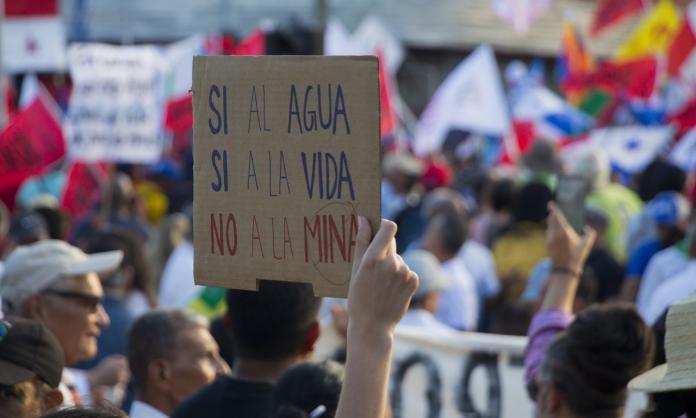

The MAS government was not able to suppress all social protest, coming into conflict over several issues. Land, indigenous and ecological issues have flared up: for example, when Morales attempted to build a resource highway through the forests of the protected native community land of TIPNIS. There have been student protests and demands over education, and dissent over the new coca laws by the cocaleros (coca leaf growers); and the handing over of the Chiquitania (tropical savanna) to Brazilian agro-industrial capital.

The Morales/Linares MAS might have taken some decisions away from the old “Golf Club”, but only at the cost of a corporatism that sought to tame the trade union and other mass organisations, and exclude any social movements and groups that would not bow to its political project, such as some of the miners’ organisations, the “ponchos rojos” and the cocaleros of Los Yungas.

In this way, the MAS government dug its own grave. It raised the economic and socio-cultural expectations of the working and middle classes (urban and rural), tied to the uncertain fortunes of “Andino capitalism”. The middle classes, who benefitted from MAS reforms, have increasingly sensed a decline in these fortunes; fearing such, they have been progressively turning on the MAS, as reflected in election results, where the MAS have dropped support by 20% since the high of the 2009 vote. The most recent elections demonstrate the changing balance of forces: Morales 47%, Mesa 36.5% and Chi Hyun Chung 8.78%. A combined majority for the right and a boost to the most reactionary populist forces, as represented by the religious right, Luis Camacho and the cruceña elite.

Most tragically, the politics of the MAS have undermined the effective political power of the organised Bolivian working class: demobilising, demoralising and depoliticising workers and handing a new influence to the mass media and the right wing (religious and racist) populism they promote.

The timid, misguided and ultimately reactionary response of the COB union federation - who in the face of the right wing claims of electoral fraud called for Morales’ resignation in order to bring “peace” – demonstrates the results of the MAS’s domesticization of the workers movement.

Morales and the MAS, pursuing the same political perspective that got them into this situation, assumed that they could save themselves by leaning on those powers who had granted them some previous license, the Organization of American States and those sections of the national bourgeoisie more motivated by their basic economic interests than their political ambitions. But after a relatively tight election result and seeing the opportunity, the cruceña oligarchy seized the initiative.

The Army’s military command took the cue, calling on Morales to resign: “Given the escalation of conflict that the country is going through and ... after analyzing the conflictive situation, we ask that the president resigns”.

It’s a sign of the political bankruptcy of the MAS, that even with an overwhelming majority of parliament’s both houses, it found itself totally isolated at the critical moment, as the forces of reaction rallied to stage the coup.

The vanguard forces of this coup are made up of the most savage, racist and reactionary elements of the Bolivian ruling class and their vengeful response is already being felt by the indigenous people as a whole and all the frontline campesinos and workers opposing the coup.

While the police and military roll into El Alto, the heartbeat of working class resistance in the outskirts of La Paz, and confrontations lead to deaths in Cochabamba, the MAS is responding with attempts to organise a roundtable dialogue with the opposition, to “bring peace” and call for new elections. “We do not want confrontation, we want peace," said the deputy of the MAS, Betty Yañiquez.

While at the same time the self-appointed new president, Jeanine Añez, has already named a new director of the National Hydrocarbons Agency (ANH), Luis Fernando Valverde; with the specific instructions of restoring fuel supplies in regions and areas where worker and campesino blockades have stopped their flow.

At this stage it looks likely that the MAS will continue down the same road that led it here, effectively amplifying the power and influence of the opposition forces and debilitating the forces organising against the coup on the ground.

The workers, campesino and indigenous organisations of Bolivia have long and deep traditions of independent, combative struggle. They will not be left out of the equation in any attempted negotiations and arrangements. Their continuing resistance to the coup and the advance of the reactionary forces will be a determining factor in the days to come. We will not have to wait long for Bolivia’s workers to rise again, and stamp their power on the future of the country.

Also on Red Flag: Excuse-makers for the Bolivian coup are enemies of democracy