Images of winding dole queues are commonly associated with the 1930s Great Depression, or the plight of workers in other countries. They are not scenes that most people in Australia today are directly familiar with. Until now.

The COVID-19 crisis has brought much of the economy to a grinding halt. Official predictions are that over the next few weeks, between 1 and 2 million people will be laid off in Australia. Qantas has already fired 20,000 workers, just days after receiving a $715 million government bailout.

There is a reason that winding dole queues are a more emotive symbol of economic collapse than, for example, pictures of panicked traders and falling numbers on the stock exchange. Mass lay-offs represent crippling hardship for working class people, and highlight the precarity of working class existence.

During times of high or full employment (at least according to official figures), this aspect of working class life is hidden. Workers might feel insecure individually, but as a whole society appears stable. Large scale economic ruptures expose just how vulnerable the majority are. It becomes obvious that despite living in a world of abundant wealth and resources, our day to day livelihoods depend upon one flimsy arrangement – employment by a boss.

When this arrangement breaks down, life is turned upside down. Often immediately. Millions of workers in Australia do not have savings to fall back upon – 40 percent of the population have no more than three weeks worth of income in their bank accounts, 10 percent have $90 or less. Around 25 percent of workers are in casual contracts with no sick leave.

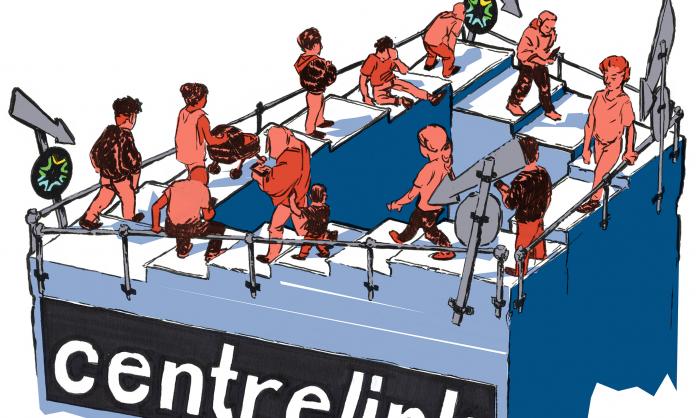

It is people in these situation that are populating the lines streaming out of Centrelink offices across Australia. Red Flag reporters talked to some of them, people visibly distressed, especially in poorer suburbs, and at a loss about how to feed their families in the coming weeks. Most were in shock, reeling from the sudden turn of events.

Ben, a 44-year-old chef from Adelaide, told a typical story: “I never expected to be back in the dole queue. I’ve been happily working for the last 10 years, earning quite good money. …I was [finishing my] shift on Sunday night, and I was clocking off, I was still on the roster for this week. Then at 9:30 there’s the announcement on the news, and the owners just came into the hotel and started packing everything up. That’s how I found out.”

Most were also frustrated. Unlike big businesses – already being showered with no strings hand-outs – ordinary people have to spend hours and days wading through the thick slow moving sludge that is the Centrelink bureaucracy just to get a pittance.

Since the lay-offs began the website has crashed countless times. Yet authorities have warned people off going into Centrelink offices. Lana from Brisbane explained her experience with this Kafka-esque dilemma outside a Brisbane Centrelink office:

“I ended up waiting for 4.5 hours. Once I was inside I waited another half hour just to be told that somehow all of my documents had already been uploaded to their system and that I need to go home and go online despite their website and their app being down, to make my booking for my appointment. So basically I stood in line and waited five hours to be told to go home and do it online. I don’t see why they couldn't have just made my appointment booking there themselves. I said how am I supposed to go online and do this when your website’s fucked and they just said good luck and keep trying.”

This is not just a case of the system being burdened with a sudden massive influx. It is a system designed to fail people.Decades of neoliberalism have seen enormous cutbacks, both in relation to staff and the amount of income support available to people. The most vulnerable are deliberately left waiting months without income while their claims are assessed.Newstart payments condemn people to live well below the poverty line – $35 dollars a day for a single adult with no dependents – and successive governments have stubbornly refused to raise the rate depite significant pressure. It is the lowest rate for any country in the OECD.

Meanwhile, the government is happy to sink money into compliance, including the illegal, immoral “robodebt” scheme that until recently hounded, humiliated and criminalised welfare recipients causing much unnecessary distress.

But for Liberals like Morrison, who last year declared the “the best kind of welfare is a job” in response to criticisms about the current rate of Newstart, the onset of an acute social crisis has changed some of the rules. Payments have been temporarily doubled, and the jobless on welfare are no longer cast as the lazy refuse of society.

Nonetheless old habits die hard: the government was caught out by the media for keeping people in the dark about the suspension of their mutual obligations. By law, these obligations can be suspended when there is no capacity to fulfil them, such as, say, during an historically unprecedented economic shut down. The mainstream media reported the government’s failure to inform current and incoming recipients of the suspension as a communication bungle.

But a public servant told Red Flag that it was a deliberate decision aimed at appeasing the job seeker providers. These “providers” do not provide at the best of times – 93 percent of their “clients” find jobs on their own – but in a time of mass lay-offs and economic shut down, their stock in trade has become farcical. The government has nevertheless offered them six months of advanced payments on their contracts.

This shows the real priorities of the government during this time of crisis. Instead of bailing out workers with welfare equivalent to the minimum wage, forcibly closing non-essential industries and forcing bosses to retain staff, they will continue to look out for private business and work to save profits wherever they can. At the moment, that involves some stop-gap measures that benefit some workers. But this will not last. We are entering an economic recession, and possibly a depression, that will see the ruling class unleash vicious attacks.

Many understandably hope that this crisis will be just a blip, and that once the worst of the pandemic passes things will go back to normal and the economy will pick up where it left off. The events of the last few weeks have been surreal, it is hard to believe that they could represent a new normal.

Yet there is no going back to how things were. It is true that many businesses and industries have been shut down by government policy and community pressure rather than because of their own economic inviability. That makes the early phase of this downturn very different to other recessions.

But the capitalist economy cannot be turned off and on at the flick of a switch. Investments that have been made in the past cannot be unmade, and the smaller and weaker companies will not survive months of hibernation as debts get called in. Individual companies as well as the economy as a whole will be radically restructured in the process, leading to many workers losing hard-won wages and conditions or their jobs.

Compounding this is the pre-existing economic malaise that the current crisis has accelerated. Growth has been weak and slow throughout the world economy since the global financial crash of 2008, and there continue to be high levels of corporate debt. The COVID-19 shut down is likely to trigger a flurry of corporate defaults and contraction in some of the world’s largest economies, which could in turn lead to crises in other economies. Regardless of exactly how profound such crises turn out to be, unemployment is likely to become a much more prominent feature of societies everywhere in the foreseeable future, including in Australia.

Australia was relatively inoculated from the effects of the 2008 crisis, which is one of the reasons that the prospect of a sustained and deep economic recession is hard to imagine. Countries that did face the brunt of the last crisis were fundamentally transformed by it, economically and politically.

In Southern Europe unemployment skyrocketed. In Spain and Greece, youth unemployment climbed to almost 60 percent. This was a key factor in sparking struggles and reshaping politics.

Young people led a massive street movement in Spain, referring to themselves as the Indignados. Their indignation powered enormous, prolonged occupations of public squares and a rejection of all of the political parties of the neoliberal establishment.

In Greece, a radical youth movement combined with an insurgent working class led to the rapid rise of a new left party that – falsely as it turned out – promised to stand up to the bosses and the bankers. Support for the traditional social democratic party collapsed.

In the Middle East, unemployment rose to similar levels and the anger of young university graduates no longer guaranteed a job was one of the factors that drove the revolutions collectively referred to as the Arab Spring.

As similar conditions set in here, the government’s mantra,“we’re all in it together” will start to lose credibility. Class tensions will become sharper and society will become increasingly polarised, opening up the possibility for shifts in mass consciousness as well as serious and radical resistance.

Even in the short-term, we are already seeing the class contradictions of the current period coming to the surface. The ruling classes’ insistence on keeping schools and various other non-essential industries running cuts against the instincts of millions of workers who want them shut in order to protect people from the virus. Unlike Morrison and the big capitalists, the majority of people do not think that “all work is essential” in the midst of a pandemic.

Meanwhile, this crisis is demonstrating that certain jobs definitely are essential, including many that are low-paid and generally not considered of much value. These workers too are demanding their right to work in safe conditions. Some are even prepared to walk off the job to insist on this, as demonstrated by the courageous walk-out by Coles warehouse workers who refuse to accept unhygienic conditions

But the dilemma facing workers everywhere is that work has always been essential for our survival – our existence is dependent upon being exploited by bosses. Even in normal times, this economic compulsion forces many to risk their health to maintain their income. So many in this time of crisis are torn between whether they are more endangered by the virus or by unemployment.

This is not a choice that should have to exist. Socialists call on workers to resist mass lay-offs, and refuse to sacrifice conditions or pay to keep capitalism afloat. But facing a long term crisis, we also have to move to a situation where workers are not dependent on the vagaries of the market. The government should guarantee our living standards while society is in lockdown, and offer opportunities for safe redeployment into industries important to fighting the virus.

But more importantly, we need to argue for a society in which the working class have real control over society and the economy. A society geared towards profit cannot respond to a pandemic in a humane and rational way. Socialist democracy would mean industries could be rapidly repurposed and reorganised without regard for the cost. Workers could be usefully and safely redeployed to perform necessary tasks, without having to worry about being thrown into poverty. People would not be forcibly coerced into dangerous employment because of economic desperation. Decisions about essential and non-essential work would be made by workers collectively and in the interests of the vast majority.

This vision of socialism requires more than centralised planning. It demands that working class people collectively and democratically take control of their lives, the economy and society.