Jack Mundey was one of the most prominent leaders of that great era of working class militancy and assertiveness: the 1960s and ’70s.

After arriving as a young worker in Sydney from north Queensland, Mundey worked as an ironworker and labourer. He eventually became active with a group of rank and file militants and communists fighting to transform the Builders Labourers Federation (BLF). The NSW BLF was then run by gangsters in the pocket of the building bosses. Labourers were at the very bottom of the pile in the industry. Their wages were crap and their working conditions even more appalling. Accidents and deaths on the job were rife. Amenities, such as eating sheds and toilets, were worse than non-existent.

It took years of concerted effort to build rank and file organisation on the job to give workers the confidence to fight back. The dedicated militants in the BLF Rank and File movement had to withstand victimisation by the bosses and bashings by the hired thugs of the BLF officials.

But things were beginning to change with the building boom of the 1950s and 1960s. A plethora of inner city high-rise construction projects led to a rapidly expanding workforce with greater skills on larger sites, and consequently greater potential industrial power for labourers. Militants began to organise together after work in the pubs around Sydney’s Circular Quay.

The corrupt right-wing leaders were defeated in the 1961 union elections by a coalition of the Rank and File committee and more moderate forces. Jack Mundey, who was playing an increasingly central role, was elected temporary city organiser in 1962 and state secretary in 1968.

The mood in the broader working class was also changing. A radicalisation was under way, notably around opposition to the Vietnam War. The late ’60s brought a surge in strike action. One of the high points was the victorious nationwide strikes in 1969 that freed the gaoled Tramways union official Clarrie O’Shea and turned the anti-union laws of the day into a dead letter.

Militant strikes by Builders Labourers – “BLs” – in the early 1970s won path-breaking wage increases and much improved conditions.

The heightened confidence BLs gained from these industrial victories, combined with the political arguments made by socialists in the union, led builders labourers to play a prominent role in fighting around a series of political issues – Aboriginal rights, the Vietnam War, opposition to apartheid in South Africa, women’s liberation (they championed getting women jobs in a previously all-male industry) and gay rights.

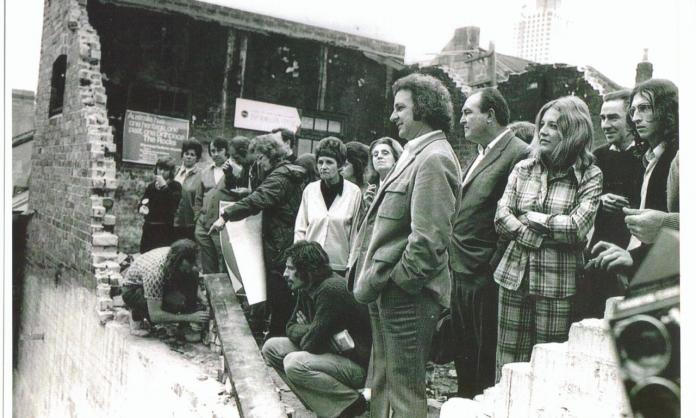

The green bans to save working class housing, heritage buildings and parkland, for which the BLF under Mundey’s leadership are most famous, did not come from nowhere. They flowed from growing industrial confidence and an assertion that workers are not robots toiling at the whim of profit-driven developers but that they should have a clear say over what they build, in the interests of the broader working class.

The BLF called for more schools, hospitals, kindergartens and homes for workers to be built, not more and more office towers. They sought to tame the concrete jungle. As one of their songs put it:

Under concrete and glass, Sydney’s disappearing fast,

It’s all gone for profit and for plunder.

Though we really want to stay they keep driving us away

Now across the Western Suburbs we must wander.

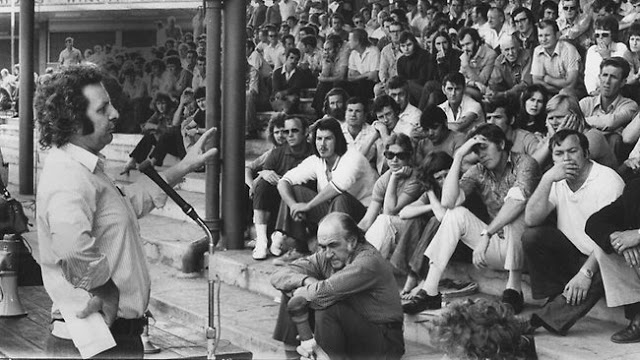

Another key factor fuelling radicalism was the highly democratic nature of the union. Key policies were thoroughly debated and decided at mass members’ meetings, not imposed by officials. The BLF militants took measures to limit the development of an entrenched union bureaucracy. Organisers regularly returned to work on the job, and Mundey himself stood down as secretary.

The BLF used a whole range of militant tactics – crane occupations, the breaking of concrete pours, flying pickets and the use of organised vigilante squads – to physically destroy work done by scab labour.

Other union officials were threatened by this militancy and the democratic aura of the BLF. And it was not just right-wing officials who condemned them.

Many entrenched Communist Party union bureaucrats, such as Pat Clancy, head of the Building Workers Industrial Union, which covered carpenters, decried the BLF’s approach as “adventurism”. It was one of the issues in the right-wing pro-Moscow split from the Communist Party to form the Socialist Party of Australia, in which Clancy played a prominent role.

Even union officials who remained in the CPA, such as Laurie Carmichael of the Metalworkers, were far from enamoured with the BLF’s militancy. Significantly, hardly any of the CPA union leaders took solidarity action in 1974 when BLF federal secretary Norm Gallagher moved to smash the NSW BLF.

The building bosses, outraged by the ongoing militancy of the NSW BLF, funded Gallagher, a member of the Maoist Communist Party (Marxist Leninist), who sent a team of gun thugs to Sydney to destroy his militant rival.

For a brief period, the CPA leadership around Laurie Aarons moved to the left in the late ’60s, away from its traditional hardline Stalinist approach, and briefly championed the radicalism of the NSW BLF. However, this shift was always thinly based, and by the mid-’70s the CPA leadership were moving relentlessly in an explicitly reformist direction, becoming some of the key architects of the wage-cutting Prices and Incomes Accord of the 1980s.

The aggressive militancy of Mundey and the NSW BLF became an embarrassment. Mundey himself, though no Stalinist, would nonetheless remain loyal to the CPA.

The fighting spirit of the BLF in Jack Mundey’s heyday is something desperately needed in today’s economic crisis, as the bosses go for the jugular to destroy wages and conditions. Decades of union bureaucrats falling over backwards to compromise with the bosses and suck up to the ALP have got us nowhere. We need to organise to turn the tide.