“The more Australians work together, the more we share the sacrifice and the burden, the more we do the right thing, the more lives and livelihoods we will save.” So Scott Morrison told the nation in late March. While he was speaking, tens of thousands of people were lining up outside Centrelink offices around the country, in Australia's first wave of mass unemployment since the Great Depression.

“So, we summon the spirit of the Anzacs, of our Great Depression generation, of those who built the Snowy. Of those who won the great peace of World War II and defended Australia. That is our legacy that we draw on at this time”, Morrison continued.

In times of crisis the entire nation – rich and poor, old and young – shares in sacrifice, so they can share in glory later. It’s a useful argument if you’re trying to convince millions to accept a pay cut.

But the history of Australia in times of crisis is a story of intense class struggle. Momentous battles between workers and rulers have determined who will pay for crises, whether in times of war or economic collapse.

Appeals to the “Anzac spirit” have flowed freely in the last few months. They conjure the image of heroic young soldiers hauling themselves across the beaches of Gallipoli, willingly sacrificing themselves for king and country. But the cynical nostalgia hides the reality of the Australian experience in World War I.

That war was fought to carve up the world between competing imperialist masters, using the world’s working class as military raw material. The initial patriotic gloss that swept Australia in 1914 soon dulled as the reality of bereavement and deprivation set in. Between 1916 and 1920, the class struggle was so intense that some of Melbourne’s ruling elite made plans to blow up the Yarra bridges should the working class northern suburbs rise in revolt.

Andrew Fisher, leader of the Labor government of the time, promised to fight to “our last man and last shilling”. His successor, Billy Hughes, made good on that pledge in 1916 when he tried to introduce conscription. Within two years, Hughes would suffer defeat in two referendums attempting to introduce conscription. Eventually, he was thrown out of his own party.

Despite the dictatorial powers to crush political dissent granted through the War Precautions Act, Hughes’ conscription campaign was confronted by a rowdy mass campaign of opposition. As the death toll from the western front mounted, so did workers’ desire to prevent youth being sent on suicide missions around the world.

Trade union branches were the locus of organised opposition. Melbourne Trades Hall convened a national meeting on conscription in May 1916, at which delegates from more than 200 unions voted almost unanimously to condemn conscription. In August, up to 100,000 trade unionists gathered in Sydney’s Domain in the first mass rally of the “no” campaign.

Pro-conscription meetings were hounded by workers. George Foster Pearce, a Labor senator and a leader of the “yes” campaign, tried to address a meeting at Collingwood Town Hall; he was silenced by a large crowd singing “We will keep the red flag flying”. A young man jumped on to his seat and put his coat on inside out, to show the crowd Pearce was a “turncoat” – a traitor to the workers’ movement.

When the vote was held on 28 October, the attempt to introduce conscription was defeated. Unwilling to admit defeat, Hughes pushed for a second referendum in December the following year. Mass opposition from the workers movement only increased, and hundreds of thousands rallied against conscription; the “no” vote increased the second time round.

Class struggle during the war peaked with the “great strike” of 1917, which drew thousands of workers into pitched battle against their bosses and the government. The spark was lit by metalworkers in the Randwick and Eveleigh railway workshops on 2 August 1917, who revolted against the introduction of a card system to closely monitor and speed up their work.

This first rebellion rode rising anger against the generalised assault on workers. The strike quickly spread along the railways, then exploded into other industries. The strike was not organised bureaucratically from above, but built from impromptu walk-offs by the rank and file.

The moaning of the manager of Central Station’s refreshment rooms in the Sydney Morning Herald in mid-August gives us a taste of the exuberant mood:

“For the past few days the girls had been rather out of hand. They were inclined to laugh and jeer at those over them, and discipline was being seriously affected. Acting under instruction, I called them all together this morning. I explained to them that they were there in the public interest, to serve anyone who should come along [they had refused to serve scabs]. I then asked those who were willing to abide by that course to stand to one side, and those that were prepared to leave to do so. Thereupon they all put on their hats and coast and marched off, amidst laughter and cheers.”

Thousands more caught the strike bug as workers across New South Wales, then Victoria and parts of Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania walked out of their workplaces and into mass demonstrations held in city centres. The next month was a long, bitter struggle. The ruling class launched a wave of repression and mobilised an army of scab labour to break the back of the strike.

Despite enormous potential, the strike would ultimately go down to defeat as union officials struck a dirty deal with the government. But there were some pockets of lasting resistance, mass rallies opposed the deal, and the seafarers and miners stayed out for another month.

Once the strike was over, bosses sought their revenge by sacking leading militants who were then denied re-employment in other workplaces, and the government deregistered several unions. It was hardly a time of national unity amid shared sacrifice.

Similar dynamics were at play when the next global mass slaughter rolled around in 1939. As the radical historian Rowan Cahill has noted:

“During World War 2 industrial disturbances increased in Australia to the point of reaching an extent greater than at any time since 1929. Some 2,210,000 man-days were lost during the period 1942-1945.”

Coal miners,working in a crucial wartime industry, were particularly combative during the war, striking against deadly new measures introduced to increase coal production. Despite the anti-strike attitudes of the ALP and the Communist Party – both of which supported the war – workers managed to slow down production, probably saving many lives.

--------

Morrison’s invocation of the “Great Depression generation” is particularly galling. The Depression was a long decade of poverty and hardship as the cost of failing capitalism was heaped on workers and the poor. Yet alongside unemployment, breadlines and homelessness, there arose mass resistance and some of the mightiest movements in Australian working class history.

A bosses’ offensive in the mines and the timber yards and on the waterfront ushered in the Depression in 1929. Workers fought back in all three battles. Though they eventually went down to defeat, their resistance set the tone for years to come.

Tens of thousands joined the Unemployed Workers Movement (UWM), organising militant blockades to stop rent evictions and street demonstrations to protest dire living conditions. When “work for the dole” schemes started in the early 1930s (public works projects paying well below award wages), UWM members organised strikes for better pay and safer conditions and against sackings.

M. Wheatly, writing in the Australian Left Review, described one such struggle:

“Seventy Bellambi relief workers went on strike for three and a half days over unhealthy job conditions and the ‘speeding-up’ tactics of the Public Works Department; when some minor concessions were made they returned to work. When they were not allowed to make up the time lost, and the ganger was sacked for refusing to speed up the work, all but one worker went on strike again. By this time the morale and determination of the men was high, and the strikers were well organised and militant. The rank and file job committee was enlarged to include relief, propaganda and entertainment committees, and public support was won at mass meetings. Strikers’ representatives spoke at meetings throughout the South Coast area ... after three weeks their demands were granted.”

This spirit of resistance would re-emerge in Australia’s next major economic crisis. The Australian trade union movement soared to new heights in the early 1970s, represented by the visionary struggles of the Builders Labourers Federation.

When Jack Mundey, the leader of the BLF’s NSW branch during the height of its radicalism, passed away recently, he was fondly remembered by militants young and old. But tributes also flowed in from the likes of Bill Shorten and Australia Council of Trade Unions secretary Sally McManus, representatives of the very same trade union bureaucracy that crushed the BLF and the militant struggle it embodied.

Industrial Relations Minister Christian Porter called McManus his new “BFF” in March, impressed by their daily conversations to manage the current crisis collaboratively. Mundey’s approach was to mobilise workers to fight tooth and nail against bosses – and, when necessary, union officials.

Builders labourers first fought to overhaul conditions in their dangerous and poorly paid industry. Years of victorious struggles over bread and butter issues inspired them to aim even higher. A culture of rank-and-file militancy, winning results by disobeying bosses and wielding strike action, led to the BLF lending workers’ power to other struggles. The first of what would become the famous “green bans” was announced in 1971 when the BLF refused to destroy Kelly’s Bush, a rare piece of bushland in Sydney’s inner north. From then on, public housing, heritage buildings and more green spaces would be saved by the militancy of the BLF.

Mundey summed up the ethos of the union when addressing a crowd of thousands assembled at the Rocks, one of their key Sydney battlegrounds:

“As long as unions exist, of course, their primary role is to struggle against the capitalist to get higher wages and better conditions. But then again, as I’ve said before, it’s not much good winning a 35 hour week if we’re going to choke to death in planless and polluted cities, where rents are too high, where ordinary people can’t live ... No longer are workers going to be driven out of Sydney.”

Despite Shorten and McManus praising Mundey now, the militancy of the builders labourers was not welcomed by the labour bureaucracy of the time. In 1974, as economic crisis again reverberated around the globe, the federal leadership of the BLF moved against the NSW branch.

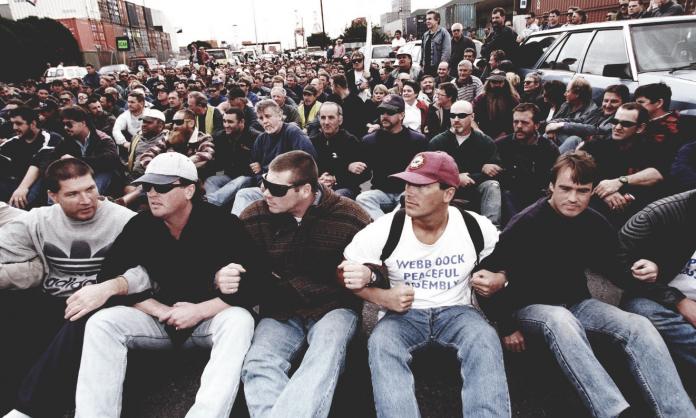

Struggle continued into the early 1980s, ebbing and flowing, as bosses moved to protect their dwindling profits by freezing or cutting wages. Miners, wharfies, metalworkers and power workers were all part of a wave of struggle from 1979 to 1981 involving 4 million workers and more than 11 million strike days.

But the era of working class militancy was finally brought to heel in 1983 when the Hawke Labor government, in alliance with the ACTU and industry heads, introduced the first Prices and Incomes Accord: in effect a guarantee to stop strikes and impose wage restraint. Some unions fought back, notably the BLF, which had signed the Accord but continued to fight for wage rises. Pilots, plumbers in NSW and Victorian nurses fought too. But rebel unions faced harsh discipline; in 1986 the BLF was deregistered nationally by the ALP. The Accord has come to represent Australia’s national tradition of class collaboration, but it reflected a hard-fought defeat for the Australian working class. It was imposed to smother their traditions of struggle and repress workers’ militancy. The result has been stagnant wages for workers. “National unity” and “compromise” were forced on workers to benefit bosses.

This is the real history of crises in Australia: not national unity, shared sacrifice or an “Anzac spirit”, but attacks from above and struggle from below.