Before mobile phones and social media became ubiquitous, it was virtually impossible for ordinary citizens to document police brutality, let alone share it with the rest of the world. Yet, more than 50 years ago, a small group of young Black activists from the San Francisco Bay Area in the US state of California succeeded in doing just that.

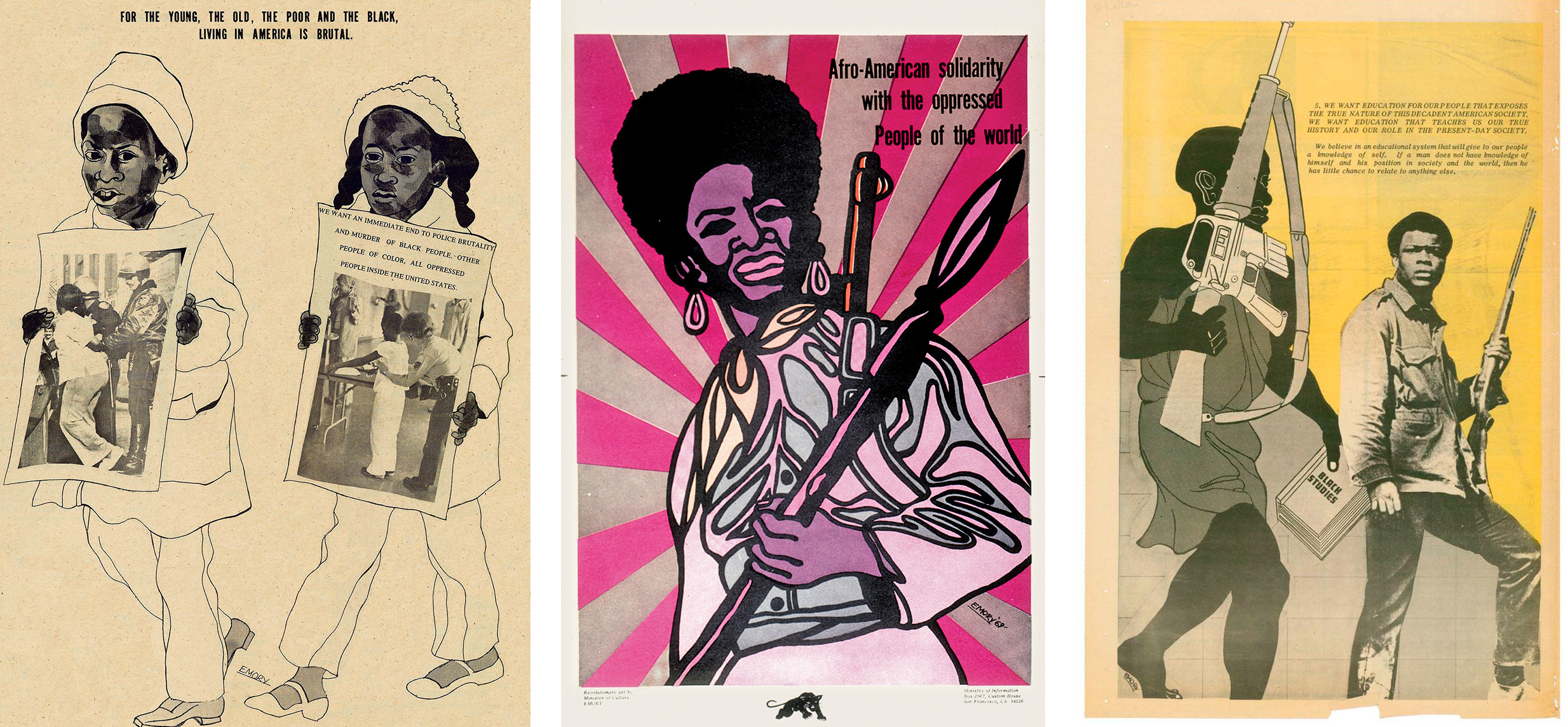

Only a few years after its formation in 1966, the Black Panther Party was distributing more than 250,000 copies of its newspaper every week. Aside from its fiery rhetoric, what made the Panther’s paper distinctive was its bold imagery. Unable to capture state violence on camera easily, party members had to be creative. The iconic woodblock-style images of Panther artist Emory Douglas became a key means to convey the Black experience of police repression.

The Black Panther Party was formed in the wake of the 1965 rebellion in the Los Angeles suburb of Watts. An altercation between police and a pregnant Black woman triggered an unprecedented outburst of pent-up anger among the city’s Black residents in August of that year, many of whom had “escaped” the Jim Crow south only to encounter a similarly racist system in the north.

As they watched events unfold, future Black Panther Party leaders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale observed community leaders in Watts “patrolling” police—witnessing their encounters and recording their badge numbers in order to prevent violence. Inspired by this initiative, the young activists decided to coordinate their own “Cop Watch”, but with one crucial difference—the Panthers’ patrols were packing heat.

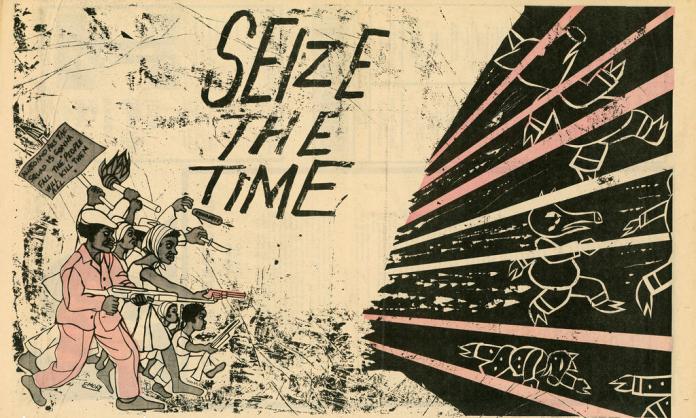

Soon after joining the party in 1967, Douglas began accompanying Newton and Seale on these neighbourhood patrols. Carrying a loaded shotgun in one hand and the US Bill of Rights in the other, the Panthers weren’t out merely to monitor the cops. By so flagrantly exercising their constitutional right to self-defence, the Panthers hoped to instil in Black people a sense of empowerment and inspire them to rise up.

Emory’s earliest party art celebrates this provocative militancy. It depicts ordinary people (unskilled workers, housewives, even children) proudly taking up arms against “pigs”—a popular epithet for police, politicians and landlords.

Douglas’ signature woodcut style was a gesture to aesthetics of national liberation struggles in Asia and Africa, with which the Panthers identified and from which they drew inspiration. Accompanying the images are revolutionary slogans, violent death threats and even declarations of civil war.

By the spring of 1971, severe state repression had put an end to the party’s militant phase. Members were forced to give up armed patrols in favour of community outreach. Throughout this period, the combative urgency of Emory’s earlier images gave way to celebrations of community solidarity.

Over time, the party splintered, some members going underground, others being coopted into mainstream politics. While its existence was short lived, the party’s revolutionary legacy lives on in Douglas’ powerful imagery. “If we wait for someone else to tell our story”, said Douglas of his art, “they’re going to paint a picture of us that doesn’t reflect our values, doesn’t reflect our agenda. So we have to lead the charge”. Douglas recognised that art, like everything else, becomes a battleground in times of intensified struggle.