When the Hungarian revolution was only four days old, Peter Fryer arrived in Hegyeshalom, a small town on Hungary’s border with Austria. Fryer had been a writer for the British Communist Party’s Daily Worker for eight years; he had reported approvingly on the Hungarian regime’s show trials in the late 1940s. Now, in 1956, he was being sent to report on what his Communist Party described as a counterrevolutionary putsch aiming to overthrow a socialist government. Fryer wrote that on his arrival in Hungary, he thought he was setting foot in “a country where ‘we’ were in power. A country where a new life was being built, where the workers were in command”. He expected to see ordinary workers enthusiastically defending the government against a fascist insurrection. What he witnessed was the opposite.

A working class revolution was attempting to free the country from the shackles of national oppression which the Russian regime was imposing upon it. The revolutionary process was developing through the construction of workers’ councils, modelled on the soviets of the Russian revolution of 1917. “I saw for myself that the uprising was neither organised nor controlled by fascists or reactionaries”, he wrote in Hungarian Tragedy, the book he published while the revolution was being crushed by Russian tanks, and which became a classic account of a modern workers’ revolution. In Hungary, Fryer witnessed "a people's revolution–a mass uprising against tyranny and poverty".

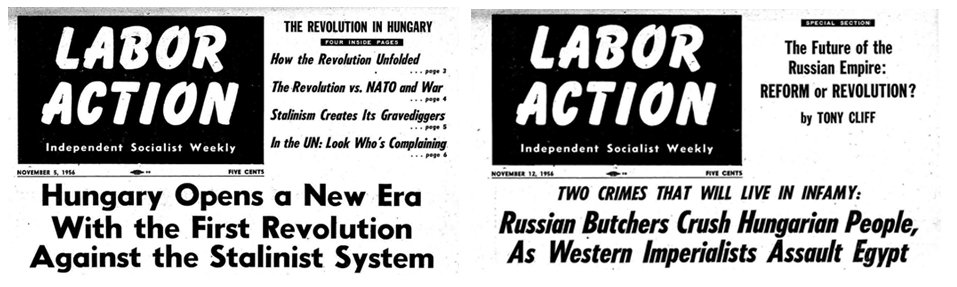

“Win or lose”, American Trotskyist Hal Draper would write in the revolutionary paper Labor Action, “the Hungarian revolution is the turning point of the postwar era”. In the depths of the Cold War, the Hungarian events proved that the working class still had the capacity to lead revolutions. It proved the “Communist” regime in Russia was counterrevolutionary. It forced the left to pick a side on the central concept of Marxism: working class self-emancipation. Do you support a working class attempting to destroy the bureaucratic and unequal society that oppresses it, or do you support the dictatorship attempting to crush it?

At the close of the second World War, Russian tanks had occupied Hungary, and with Western approval, a Russian-backed dictatorship was established.

By this time, workers’ power had been snuffed out in Russia. In 1917, revolutionary workers’ councils had taken power, hoping to be followed by workers elsewhere; within a few years, the revolution was isolated and the workers’ councils had been wiped out by famine and by a civil war. In the ashes of the revolution, Stalin and a bureaucracy around him rose to power. The goal of international revolution was abandoned, and socialism was redefined as the iron rule of bureaucratic Communist Parties. Stalin’s Russia abandoned support for self-determination by oppressed nations. Lenin had declared that “no nation can be free if it oppresses other nations”; Stalin’s Russia subjugated countries across Eastern Europe.

Russia dominated its Eastern European satellite states as if they were its colonial possessions. Whole factories were dismantled to be rebuilt within Russia itself. Russia’s satellites were forced to sell raw materials to Russia far below market rates and often below cost price. The cost was borne by the workers; in Hungary, real industrial wages fell by 18% between 1949 and 1952.

Censorship was the norm, and workers lived in fear of torture or imprisonment by the secret police, the AVH. The AHV conducted large scale purges within the Hungarian Communist Party, the broader working class and the intelligentsia to eliminate opposition to the rule of Russian-backed dictator Mátyás Rákosi. But they couldn’t eliminate the anger, bubbling below the surface, at the harsh living conditions and lack of political freedom.

In 1953, Stalin died. His replacement, Nikita Khrushchev, executed and purged opponents, but to achieve long-term political stability he needed to broaden his support base. Stalinist repression was holding back Russia’s capacity to compete with other capitalist states. To increase productivity, Khrushchev needed more skilled workers and an element of consent to go with Stalinist coercion. So Khrushchev relaxed some of the more extreme forms of political repression of workers in Russia. In February of 1956 he made his famous “secret speech” confirming Stalin’s crimes to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Despite hopes that the speech may mark the beginning of a real shift in the country, Khrushchev did not fundamentally change the character of the Russian state. Even when it was “destalinising”, it remained a “Stalinist” state in its fundamental structures: one in which a bureaucratic ruling class operates a political dictatorship, using its state power to control the means of production and exploit the working class, while proclaiming that it is doing so on behalf of the workers themselves. But those workers, both under Stalin and Kruschev, were deprived of any real control over either production and politics.

But the speech exposed before the eyes of the world the dark reality of what had been happening in Russia: “the usage of the most cruel repression, violating all norms of revolutionary legality, against anyone who in any way disagreed with Stalin, against those who were only suspected of hostile intent, against those who had bad reputations.”

The battle at the top of the Russian regime threw the Eastern European satellite states that Russia controlled into crisis, creating confusion and rifts in the bureaucracies that controlled them. In Hungary, Imre Nagy was installed as leader in 1953 in order to lead reforms which could placate workers, but he was replaced with Rákosi again in 1955. Following the secret speech in 1956, Rákosi was replaced with Ernő Gerő. Nagy’s brief rule as a reformer inspired hope in Hungarian workers and intellectuals, and his ousting was remembered with outrage.

In Poland, a rebellious workers’ movement began in June 1956. Hungarian students, inspired by those resisting and being repressed, organised a demonstration “in solidarity with our Polish brothers” in October.

The government originally allowed the demonstration, but backflipped on the day and withdrew permission for it to take place. But the last-minute decision had no effect except to radicalise the demonstration. Over one hundred thousand students and workers came out into the streets, and they were now doing it in defiance of an order from a totalitarian government. A section of the demonstration marched to destroy the statue of Stalin that stood in Városliget, Budapest’s huge city park. “Once numb, now David took his stance and down fell the statue of Goliath”, wrote poet Lőrinc Szabó.

The official government response to the demonstration, broadcast nationally on radio, condemned those in the streets as enemies of the people who had “taken advantage of our democratic liberties to organize a nationalist demonstration”. The broadcast stoked the anger of the protesters.

Students tried to use portable radio equipment to broadcast their speeches, but it didn’t work. They began to march to the radio headquarters to force their message onto the air. When they got there, soldiers fired into the crowd. The demonstration became a pitched street battle. Soon afterwards, the police chief Sandor Kopacsi would receive the chilling news that rebellious Hungarian soldiers had begun providing arms to the demonstrators so they could defend themselves against the next attack.

The Russian regime was determined to protect its hold on the country. Overnight the Russians sent in 1,100 tanks and 30,000 troops. While the tanks were rolling in, workers were beginning to join the students.

Leslie B. Bain wrote in the New York Reporter that “it was 4am when the first Soviet tanks and armored cars arrived … Workers in the suburbs had held meetings and drawn up demands generally in line with those of the students. To these had been added several specific points about factory-management councils and general increases in wages. At dawn the workers began marching into the city”.

Over the following days, demonstrations in town after town were met with machine gun fire by the AVH. Now the fire of revolution burned across the country. Although the revolution had been sparked by a student demonstration, the Hungarian workers were providing it new strength. “We believe that today the most important thing is not military measures, but domination over the masses of workers”, Anastas Mikoyan and Mikhail Suslov reported to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s Central Committee Presidium on October 26.

A 28-year-old refugee told the Observer “the young workers were the power of the revolution”. No longer were they the dominated victims of a repressive regime. They were now grasping hold of history and shaping it themselves, like the Russian workers of the generation before them.

“Of course, as in every real revolution ‘from below’, there was ‘too much’ talking, arguing, bickering, coming and going, froth, excitement, agitation, ferment”, Peter Fryer would write. “That is one side of the picture. The other side is the emergence to leading positions of ordinary men, women and youths whom the AVH dominion had kept submerged. The revolution thrust them forward, aroused their civic pride and latent genius for organisation, set them to work to build democracy out of the ruins of bureaucracy. ‘You can see people developing from day to day,’ I was told.”

From the outbreak of the revolution, workers began to establish new democratic organs to coordinate the movement. The councils were made up of workers elected after debates in each workplace. They were directly accountable to their workmates, and instantly recallable. Often students, soldiers and intellectuals joined the councils or had their own institutions, but the revolution was led by workers. Workers were not only its power base; they were the ideological leaders of the revolution, setting the political terrain of the revolt through the debates in their councils. The inspiration for these councils came from those established by Russian workers in 1917, known as “soviets”.

The Stalinist construction of a bureaucratic state had so warped the meaning of the word that by 1956, Mikhail Suslov, one of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's key leaders dealing with the Hungarian uprising, could report to a presidium meeting with not a whit of irony that “councils are being formed (spontaneously) at enterprises (around various cities). There is an anti-Soviet trend to the demonstrations.”

The councils debated demands to place on the government. The most prominent demand across the councils was for national liberation: the end of Hungary’s subordination to Russia. The revolutionaries flew the Hungarian flag with the Russian emblem torn out from its middle. Many of the councils took up the demand for workers’ control of production.

Also prominent was the demand for the reinstatement of Stalinist reformer Imre Nagy as president. Some began to settle on a program of socialism. The Miskolc Workers’ Council and Student Parliament proclaimed “we workers, students and armed forces under the leadership of the Miskolc Workers’ Council and Student Parliament demand a new provisional government, truly democratic, sovereign and independent, which will fight for a free and socialist country”.

Capitalism–its Stalinist form included–deprives workers of control over society. No parliamentary reform can change that dynamic. But the councils gave workers a means through which to directly take control of the world around them. Through their own revolutionary power, workers could collectively make decisions about not only the economy–what to produce, how to produce it, where to distribute it, and for what purpose–but also about politics.

For the first time in decades, the spectre of true communism had returned to Europe.

On 1 November, the Russians sent in a new round of tanks. Imre Nagy, a figure of reform in the eyes of many Hungarians, had been appointed to lead a new government early on in the revolution, hoping to stabilise the country. Now he was dismissed, and Russia sent 200,000 troops and 3,000 tanks to occupy the country.

The revolutionaries resisted heroically. They fought in desperation, not only to save themselves but to defend the glimpse they’d had of a new world. It was workers who led the battle. Hospital statistics indicate that they made up 80% to 90% of those injured. Peter Fryer left a heartfelt account of the invasion:

In public buildings and private homes, in hotels and ruined shops, the people fought the invaders street by street, step by step, inch by inch. The blazing energy of those eleven days of liberty burned itself out in one last glorious flame. Hungry, sleepless, hopeless, the Freedom Fighters battled with pitifully feeble equipment against a crushingly superior weight of Soviet arms. From windows and from the open streets, they fought with rifles, home-made grenades and Molotov cocktails against T54 tanks. The people ripped up the streets to build barricades, and at night they fought by the light of fires that swept unchecked through block after block. In the hospitals crammed with wounded, operations were performed without anaesthetics while shells screamed and machine guns sputtered. I was heart-sick to see the army of a Socialist State make war on a proud and indomitable people.

Workers continued to resist for six weeks. The councils launched a general strike which cut industrial production by 80 percent for over a month. But the new regime took advantage of the lack of international support for the revolution.

The new government used a combination of different tactics to fully defeat the uprising. On the one hand, repression: arrests, sackings, persecution of leading activists. On the other hand, co-optation: incorporating neutered versions of workers’ councils into the factory management process, granting some concessions to workers. Once things stabilised, Kadar met new strikes and demonstrations with heavy repression. In December, the regime rounded up 200 council leaders. Workers who protested against the arrests were shot down in the streets.

In the end, the defeat of the revolution came down to its isolation. The working class across Eastern Europe sympathised with the revolution, but the communist parties in each country worked hard to diffuse any solidarity and ensure that a mass movement of the working classes of the satellite states could not be built.

In Romania, for example, the political committee of the ruling Workers’ Party came to the conclusion that while it was necessary to hold meetings in the factories and barracks to give workers the party line on the Hungarian uprising, “care should be taken not to organize too many meetings at the same time, so that control [over these meetings] and the participation of members from regional, county, and city party committees can be ensured”. The committee put considerable effort into deciding on an explanation for the uprising that would avert a sympathetic uprising in Romania. They weren’t entirely successful: clandestine student committees formed and organised significant student demonstrations. But the actions of the party in curtailing the movement, and the absence of any truly revolutionary mass party which could organise against it, meant that the protests were limited. Similar dynamics were seen throughout Eastern Europe.

The Western capitalist powers, too, left the Hungarian revolutionaries for dead. France, Britain and Israel were in the process of their own invasion of Egypt, and so opposed any measures in the United Nations which would set a precedent condemning invasions. The Suez Canal had been nationalised by President Gamel Abdel Nasser just months before the revolution, and the Western powers sought to regain control over it.

France and Britain resisted the Hungarian question being debated at the UN Security Council. When it finally was to be discussed at the Security Council, the French foreign minister insisted that “it is essential that the draft resolution which will be put to the Security Council on the Hungarian question should not contain any disposition which may disturb our action in Algeria and our relationship with Morocco and Tunisia. We are particularly against the formation of a committee of inquiry”.

The crisis in Egypt helped to distract the world from the butchery being meted out in Hungary. The Hungarian Revolution was crushed, and governments the world over–whether aligned to Russia or the West–allowed it to happen.

Hungary’s workers proved Marx’s contention that working class struggle can lay the basis for revolutionary socialist democracy. They proved that this project requires the destruction of Stalinist states and politics, just as it requires the destruction of Western-style capitalist states.

But this distortion of Marxism was ground down in the face of reality. Some Communist Parties ruptured and suffered splits. While there had been upsets causing splits among the Stalinist parties in the past, notably the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939, the Hungarian revolution fractured some of the key parties in a more serious way, and proportionately more of those who left were radicalised to the left rather than drifting into liberalism.

In Britain, over 10,000 left the Communist Party in the months after the revolution. The Italian party suffered a serious split, and the French leadership fractured. The membership of the American party dropped from 50,000 in the immediate postwar period to 3000 after 1956. Soon Stalinism would enter decades of prolonged crisis, as the ultra-Stalinist Chinese government split from the Russians, denouncing them as “fascists” too, and accelerating the ideological death spiral of the organisations that sought inspiration in totalitarian “Communist” powers.

Among the British Communists, rank-and-file workers were particularly affected. Norman Harding, a factory worker, recalled in his memoirs: “The worker comrades in the CP were horrified. When strikes took place in Britain the media always worked on the lines that the strikers had been worked up by communist agitators. We all know that workers will not simply strike because they are told to. There have to be conditions prevailing to get the workers angry to respond to leadership. These criteria also applied to the workers’ uprising in Hungary.”

The party intellectuals, too, were affected. The young EP Thompson, soon to leave the Communist Party, wrote: “Where is my party in Hungary? Was it in the broadcasting station or on the barricades? And what is it? Is it a cluster of security officials and discredited bureaucrats?”

But just as the revolution demoralised and split the communist parties, it gave “new life and new substance to the socialist struggle against capitalism”, Hal Draper argued at the time. It strengthened the resolve of the revolutionary organisations from the tradition that embraced socialism but rejected Stalinism, particularly in the Trotskyist movement. It provided a vision of a modern workers’ revolution that created the embryo of a democratic workers’ state in its revolutionary councils.

While researching this article, I had the opportunity to speak to Ervin Janek. Janek was 17 years old and a political prisoner of the Hungarian regime when the revolution began. He was freed by the revolutionaries and handed a gun, he joined the revolution before he could fully understand what was happening. When we spoke on the phone, Ervin’s partner explained that communists had rolled in tanks to suppress the revolution. Ervin protested. “They were not communists.”

If the Hungarian revolution is to teach us anything, it should be this: communism is not dictatorship over workers. Communism is a classless society created by working class revolution, and the seeds of communism lay in all struggles of workers and the oppressed against injustice and tyranny. Today, that lesson matters on the left. It determines whether you support the workers and students of Hong Kong in resisting encroaching dictatorship; whether you support the workers in Belarus struggling against a dictatorial regime.

In the preface to his History of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky wrote:

The most indubitable feature of a revolution is the direct interference of the masses in historical events. In ordinary times the state, be it monarchical or democratic, elevates itself above the nation, and history is made by specialists in that line of business–kings, ministers, bureaucrats, parliamentarians, journalists. But at those crucial moments when the old order becomes no longer endurable to the masses, they break over the barriers excluding them from the political arena, sweep aside their traditional representatives, and create by their own interference the initial groundwork for a new régime.

This is what the Hungarian workers accomplished. A future communist society will follow in their revolutionary footsteps, not in the tradition of the bureaucratic dictatorship that crushed their uprising.