We have been constantly told during the COVID-19 pandemic that we must follow the advice of the experts. As health experts are guided by what we believe to be objective data and science, many feel no need, or don’t feel confident to be critical of expert opinion. For the most part, this is a good thing. But what happens when different groups of experts have wildly divergent views?

Such is the case with expert advice on the best ways to deal with COVID-19 pandemic. In the early months of the pandemic, some health advisors—such as Sweden’s chief epidemiologist Anders Tegnell—championed herd immunity, while those in Australia and New Zealand advocated for widespread restrictions to suppress transmission. Individual health experts have, in addition, been inconsistent in their advice. Victoria’s Chief Health Officer, Brett Sutton, for example, has shifted his opinion around masks, the safety of schools and who should be tested on what sometimes feels like a weekly basis. Clearly, there is more to expert opinion than the objective truth, and we must consider the influence that capitalist ideology has in shaping the advice health experts are providing about COVID-19.

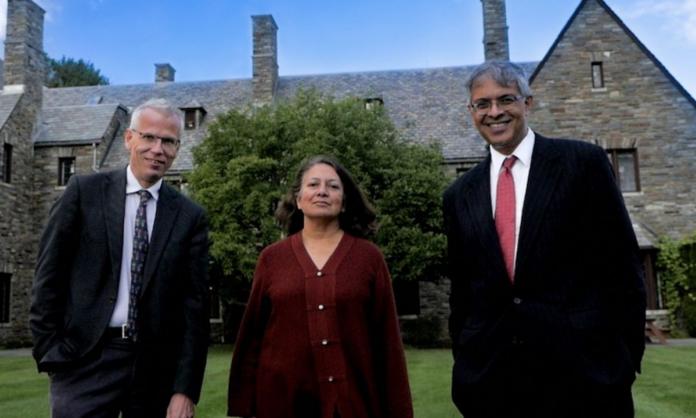

The Great Barrington Declaration is one of the most recent cases that has provoked major controversy among health experts. Authored by three professors in infectious disease and epidemiology from Harvard, Stanford and Oxford universities, the Declaration claims that lockdowns are devastating for public health and proposes an alternative “focused protection” strategy.

The strategy is based on evidence that the risk of dying from COVID-19 differs significantly by age, and therefore proposes that younger, less vulnerable people, should resume life as normal, while older, more vulnerable people continue to isolate. As younger people are infected with the virus, so the theory goes, the population will eventually develop herd immunity to protect more vulnerable elderly people.

The Declaration appears to have gained a reasonable amount of support since its publication on 5 October, reporting signatures from over 11,000 scientists, 31,000 medical practitioners and 569,000 “concerned citizens” globally. Even some sections of the left seem open to the strategy it outlines, with US publication Jacobin, for instance, running an interview with one of its authors, Dr Martin Kulldorff, where he was able to pitch his “radically different approach to the pandemic”.

Other health experts, however, have strongly disputed the Declaration’s claims. Shortly after the publication of the Declaration in October, 31 health experts published a response in the prestigious medical journal the Lancet. These authors voiced concern that the herd immunity strategy outlined in the Declaration represents “a dangerous fallacy unsupported by scientific evidence”. They argue that there is no evidence herd immunity is achievable through natural infection and that “uncontrolled transmission in younger people risks significant morbidity and mortality across the whole population”. Instead, they insist that governments should continue to implement measures that control community transmission of COVID-19 until we have effective vaccines and therapeutics.

The response highlights that there is nothing “radically different” about the strategy outlined in the Declaration. It proposes the controversial herd immunity approach, re-branded. We can look at the UK as a most recent example of how this strategy unfolds. The UK until recently implemented “shielding” for vulnerable populations, ordering them to isolate during periods of high virus transmission while the remainder of the population was less restricted. The UK is now recording over 20,000 COVID-19 cases per day, hundreds of daily fatalities, and is about to enter a second lockdown to slow transmission. This suggests the ability to both clearly identify and protect vulnerable people during periods of high virus transmission in the population is pure fantasy.

Some may still want to argue that a focused protection strategy could be more effectively implemented than what was attempted in the UK. However, the evidence that this will result in herd immunity doesn’t exist. The authors of the declaration admit they don’t know what percentage of the population needs to be infected with the virus to achieve herd immunity, so how can they insist that infection of young and healthy people will be sufficient to protect the population? Secondly, emerging data indicates that immunity from natural infection with COVID-19 can decrease over time, and there have been several cases of reinfection with the virus, bringing into question whether herd immunity can be achieved without a vaccine.

Finally, the Declaration ignores the health outcomes of survivors of COVID-19, which raises more concerns. The list of potential complications that can occur in patients (including young people) who have recovered from COVID-19 continues to grow, including chronic fatigue like-illness, heart problems and lung damage. And because this virus is quite new we won’t know for many years what the long term effects on health will be.

There appears to be a strong scientific case, then, against the proposals put forward in the Declaration. However, relying on the scientific evidence alone to pick a side has its limitations. You enter into what appears to be a perpetual debate. Just like many scientific debates, both sides continue to claim apparently “objective” evidence for their strategies, pick apart the other side’s arguments and identify holes in their evidence.

Both sides insist their strategy is in the best interests of public health. In the case of the authors of the Declaration, this centres on the consequences, for public health, of extended lockdowns. For the authors of the response in the Lancet, the argument is that a herd immunity strategy will have vastly greater public health consequences. And even if we believe the scientific evidence against the Declaration is stronger, this doesn’t address why the authors of the Declaration got their conclusions so wrong. To fully understand this, we need additional ways to judge the arguments being made.

It’s here that we must look at the role that capitalist ideology inevitably plays. Science doesn’t exist in an apolitical vacuum. Scientific data may be objective, but there is a lot of space for subjectivity in how the data is interpreted and presented. This use of science is shaped, just as much as any other aspect of human endeavour, by the ideological currents that dominate the capitalist society we live in.

You don’t have to scratch the surface too deeply to see that the Declaration was a politically motivated, right-wing manoeuvre. The location for writing it, and the resources required to publicise it, were provided by the American Institute of Economic Research, a right-wing libertarian think tank that has published constant propaganda about the negative effects of lockdowns on the economy. One of Declaration’s authors, Dr Jay Bhattacharya, is a close colleague of Dr Scott Atlas, the lunatic pandemic health advisor to US president Donald Trump. The Declaration has become a key feature of Dr Atlas’s Twitter frenzies labelled with hashtags #LockdownsKill and #TruthPrevails, and is being used to justify Trump’s criminal approach to the pandemic that has long prioritised opening up the economy over people’s lives.

This gets to the heart of what is wrong with the Declaration: its purpose is to disguise a health strategy for capitalism as a strategy for public health.

The fact that there are some health experts prepared to advocate a pandemic strategy that is being used to put capitalist profits above human lives shouldn’t surprise us. The world of science, just as much as any other part of society, is powerfully shaped by the interests of big business. The priorities of capitalism dictate what ideas are researched and funded, and which results and conclusions are publicised. This will inevitably result in the promotion of scientists and experts who are most accepting of the limitations of capitalism and develop ideas that align with those that the run the system.

In our assessment of expert opinion, we would do well to always keep this dynamic in mind. A rigorous assessment of expert advice and scientific claims must include a political assessment of how science is being used and who stands to benefit from it.