Almost a year after being overthrown in a right-wing coup, the Movimiento al Socialismo (Movement Toward Socialism, or MAS) emerged victorious in Bolivia’s presidential elections, held across the country last month. Despite hundreds of troops and police patrolling the streets on election day—and a campaign of intimidation and persecution that attempted to jail MAS presidential candidate, Luis “Lucho” Arce, along with dozens of other leading party officials—MAS won 55 percent of the vote, securing a two-thirds majority in the Chamber of Deputies of the Plurinational Legislative Assembly (ALP). The centre-right candidate, Carlos Mesa, and his Comunidad Ciudadana (Civic Community, or CC) received 29 percent of the vote. The fascist candidate, Luis Fernando Camacho, and his newly formed Creemos (“We Believe”) coalition, won 14 percent.

The result is a humiliating defeat for the pro-coup coalition: sections of the urban middle classes, large-scale agribusiness, cattle-ranchers, loggers and extractive capitalists of Bolivia’s eastern lowland departments, the police, armed forces, judiciary, fascist paramilitary gangs and their political representatives in Jeanine Áñez’s “interim” regime installed last November. And the result is a clear rejection of the coup-bloc’s pro-business and racist agenda by the country’s working-class and Indigenous majority.

MAS won six out of Bolivia’s nine departments: a clean sweep of the high plateau regions of La Paz (68 percent), Oruro (63 percent) and Potosí (58 percent); two out of the three tropical valley regions, Cochabamba (66 percent) and Chuquisaca (49 percent); and the eastern lowland department of Pando (46 percent), a region traditionally associated with the Bolivian right.

“These election results demonstrate that the coup regime’s rule—with its disastrous mismanagement of COVID-19 that has resulted in more than 8,500 deaths, an economic collapse that has left millions out of work, harsh repression and the political persecution of the regime’s opponents, alongside the increased impoverishment of the Indigenous rural population—has played a huge role in pushing sections of the urban middle classes that had abandoned the previous MAS administration back into their camp, as well as cohering the traditional urban and rural working-class and Indigenous support base of the MAS in the western highlands and highland valleys”, Javo Ferreira, editor of socialist publication La Izquierda Diario Bolivia, says via email from La Paz.

“While the revulsion generated by the Áñez regime has played an important role in the coup-bloc’s electoral defeat, the country’s powerful social movements played a decisive role in securing the existence of these elections”, Javo says. “The coup regime postponed the elections three times, and they were preparing to postpone them again. It is clear that we would not have had elections if there had not been a mass movement that took to the streets [in August], occupied the roads and bridges, and forced these elections to take place.”

Divided by internal disputes, the pro-coup bloc has been unable to use its control over the state apparatus and tilt the balance of class forces in its favour. Despite Áñez withdrawing from the presidential race in September in an attempt to unite the pro-coup bloc, the right-wing vote was split between Mesa’s CC coalition and Camacho’s Creemos in a number of important municipalities and departments. (For example, the combined vote of the right would have delivered them victories over the MAS in both Chuquisaca and Pando.)

Despite these setbacks, the coup-bloc has made important gains in some areas. In the eastern lowland department of Beni (Áñez’s home state and a stronghold of the country’s powerful agribusiness and cattle-ranching interests), Mesa’s CC coalition won the region back from MAS. Likewise, in a significant realignment in the eastern lowland department of Santa Cruz—home to the most violent and reactionary sections of the Bolivian elite and their Christian fundamentalist traditions—“Macho” Camacho, who played a leading role in the violent street mobilisations in the lead-up to last November’s coup, has consolidated as the political face of the country’s growing fascist and paramilitary right.

The extreme right that Camacho represents—interlocking networks of small and big business owners united through “respectable” civic committees (local business councils), and the increasingly confident fascist gangs, militias and paramilitaries working in tandem with Bolivian security forces to carry out attacks on left-wing opponents—now has sixteen deputies and four senators in the ALP. (According to a report published by Harvard’s International Human Rights Clinic, the largest and most prominent of these fascist groups, the Resistencia Juvenil Cochala, based in Cochabamba, has grown from 150 at the time of last year’s election, to 5,000 members locally and as many as 20,000 or more nationally.) Camacho’s electoral gains provide the extreme right with an important base in Santa Cruz and in the halls of the ALP, from which their leaders can articulate a national political project that connects with the growing number of fascist “shock troops” that have emerged in the western and central valley departments.

“This new context has opened a unique political situation in which the mass movement that has been fighting the coup-bloc will now have the opportunity to complete this political experience—but now under a new MAS government in conditions completely different from those of the previous fourteen years of Evo Morales governments”, Javo says.

Unlike the previous Morales administration—which used Bolivia’s natural gas and hydrocarbon reserves to bankroll social spending programs for the poor—Arce inherits an economy that has been pulverised by COVID-19. According to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia, more than 700,000 people have lost their jobs during the pandemic, with the total number of unemployed in the country surpassing 2 million people (Bolivia has a total population of 11 million).

The new administration also inherits a series of international loan repayments established by the outgoing Áñez administration, including US$240 million owed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and US$324 million to the World Bank. Importantly, the fall in global commodity prices has hit the country’s state-run hydrocarbon and gas firms and their connected state-coffers particularly hard, the IMF predicting an 8 percent drop in Bolivia’s GDP this year—the worst slump in more than three decades.

Arce has proposed an economic recovery based on Bolivia’s vast lithium reserves—estimated to be worth approximately US$200 billion at current prices. According to Arce, the modernisation of Yacimientos de Litio Boliviano, the state-run lithium company, will allow the firm to both mine lithium and refine it into lithium hydroxide and other compounds used in rechargeable batteries and solar car manufacturing.

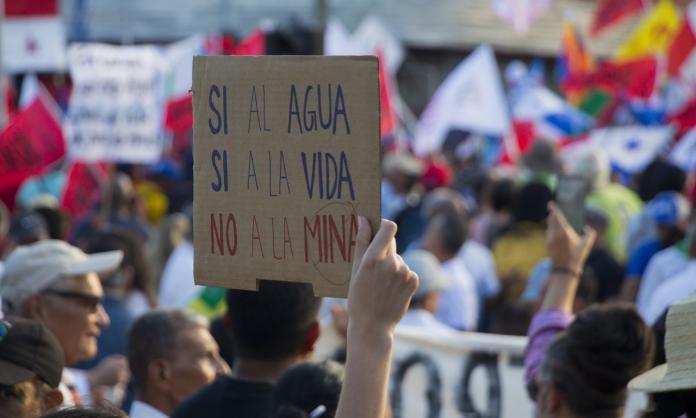

“It is difficult to see the immediate economic impact of this plan because lithium production, at the time of the coup last year, was in its infancy”, Javo says. “Moreover, the environmental destruction of such projects is well known—the poisoning of local water supplies, chemical leakages, soil and air pollution and so on. Environmental concerns have been a source of major grievances for many Indigenous communities over the years, and a point of fierce conflict with the previous MAS administration. It will likely be for this one as well.”

To contain potential resistance, MAS has brought together many of the country’s largest and most powerful trade union and peasant-Indigenous federations under the banner of a “Pact of Unity”. Like all agreements of this nature, the national unity pact is designed to co-opt trade union and peasant-Indigenous leaders into the project of rebuilding capitalist industry, policing their most militant members and ensuring independent struggles against the government do not take place.

Instead of acting as the “political instrument” of Bolivia’s social movements (which is how MAS self-identifies), MAS is acting as the political instrument of a bureaucratic clique that wants to collaborate with capital and the state. Instead of building socialism—which would entail building the confidence of Bolivia’s working-class and peasant-Indigenous peoples to take direct control over the productive apparatus of society—MAS will continue building a version of “Andean-Amazonian capitalism” (to use a well-known slogan of former vice-president Álvaro García Linera), in which a section of the union and social movement bureaucracies manages state-run companies.

This bureaucratic and conciliatory approach to politics explains why, despite its important electoral victory, MAS is unable to replicate the electoral triumphs it secured in the 2000s and the earlier years of this decade, when it regularly secured more than 60 percent of the vote nationally. (The precondition for those electoral victories was a series of insurrectionary struggles against the Bolivian state that MAS has worked tirelessly to channel into state and industry building.) This class-collaborationist approach to politics created conditions more favourable to the right, which was able to capitalise on growing discontent and cynicism and overthrow MAS in the November coup last year.

In his opening address to the Pact of Unity on 29 October, Juan Carlos Huarachi, executive secretary of the Central Obrera Boliviana (Bolivian Workers Centre, or COB), the country’s chief trade union federation, said: “All the popular movements that have taken part in the historic struggle for the recovery of our democracy are here to support our comrades Lucho [Arce] and David [Choquehuanca, the Indigenous leader and vice-president-elect]”. In a similar tone, representatives from the Confederation of Peasant Women (“Bartolina Sisa”)—who’s offices in La Paz, alongside those of the COB, were firebombed by fascists in August—spoke of the need for “reconciliation and “forgiveness” to avoid further polarisation when legal prosecutions against members of the coup-bloc for its crimes and human rights abuses begin in coming months.

Those who faced murderous repression under the coup regime over the past year—the victims of massacres in Ovejuyo, Senkata and Sacaba, the hundreds tortured in the police stations of El Alto in the days after the coup, and the hundreds of opponents of the regime, many of them MAS members, currently languishing in prisons across the country—might not feel so conciliatory, nor so forgiving. But neither will the coup-bloc, which will view any conciliatory attitude on the part of the MAS and the Pact of Unity as an opportunity to win political concessions as it works to destabilise the Arce administration and plot another coup.

The far right is already exploiting these signs of conciliation. In late October, Orlando Gutiérrez, executive secretary of the Union Federation of Bolivian Mine Workers—who was tipped to be the new mining minister in Arce’s government—was attacked by fascist paramilitaries in La Paz. He died several days later from the injuries inflicted. In the lead-up to Arce’s inauguration on 8 November, the Comitê Cívico de Santa Cruz (Pro-Santa Cruz Civic Committee) initiated road blockades in the eastern sector of Chiquitano, across the city of Santa Cruz and throughout the department, forcing businesses to close in protest against the election results. On 5 November, a stick of dynamite was pitched into a MAS campaign office in La Paz in a failed attempt on Arce’s life.

In response, Arce has offered an olive branch to those sections of the coup-bloc, such as Mesa and his CC coalition, that have refused to back the recent actions of the extreme right. “The threat posed by the far right will not be defeated through conciliatory measures aimed at stabilising the situation in Bolivia”, Javo says. “The coup-bloc will only truly be defeated by advancing those sections of workers and Indigenous peoples that forced them into the mistake of calling these elections, and mobilising them in confrontations that drive the far right from the streets for good.”