Various commentators, including Adam Schwab in Crikey, have proclaimed that it is a major contradiction for leftists, “who once championed human rights and freedoms” to back the state “adopting authoritarian methods of dealing with the virus”.

But the contradiction is largely in the heads of these commentators. The most basic human right for workers is the right not to die in their millions from a horrific disease caused by rapacious capitalist exploitation of the natural world. That is the basic right that the left needs to champion in the present pandemic. That is why the left should vigorously oppose the cry, constantly raised by business owners and right wing politicians, to open up and “learn to live with the virus”. We know full well that it will not be the rich that suffer the most if the virus is allowed to run rampant. It is workers, the poor and the oppressed.

Yes, working class people are suffering during the lockdowns. That makes fighting for much improved income support, job guarantees and better social services also vital.

There is a long history of the workers’ movement and the left stridently campaigning for state intervention to deal with issues of public health, education, and working conditions, through restricting the rights of business owners. Those working class campaigns were routinely denounced as an assault on “individual freedom”, both by right wingers and many small-l liberals.

Just over a hundred years ago, at the time of the last great pandemic (the so-called “Spanish” flu), waterfront workers and seafarers in Australia took industrial action demanding governments enforce much tighter quarantine restrictions on people arriving by boat. These actions saved untold lives.

Only a few years earlier, these same workers had taken strike action in support of the successful left-wing campaign against conscription of workers to die in the imperialist war. Indeed, there have been numerous left-wing, working class campaigns to defend the democratic right to politically organise, to protest, for the right to strike, against anti-abortion laws, against racist police and so on. Left-wing militant workers have been quite capable of championing genuine democratic rights, while at the same time demanding state intervention to clamp down on rampant exploitation and the reckless behaviour of bosses and small business owners.

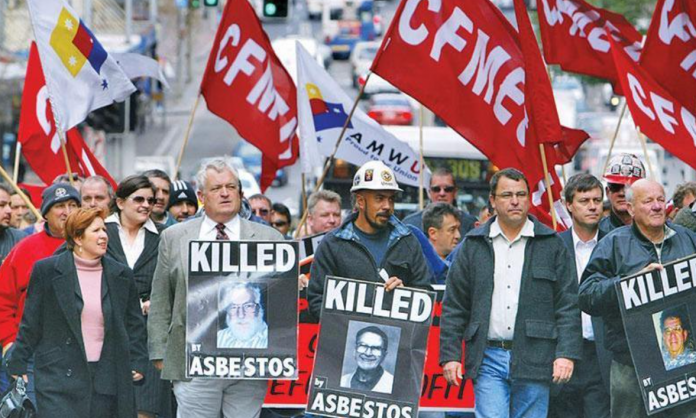

The working class movement long fought for the banning of children from working in mines and factories, for health inspectors to regulate the quality of food sold in shops and restaurants, for banning polluting factories from working class neighbourhoods, for compulsory school attendance, for banning asbestos, for compulsory tests for diseases such as tuberculosis and lead poisoning. That is but a small sampling of hundreds of years of heroic struggles around pretty much every area of working class life.

Capitalists, small business owners and middle class professionals repeatedly invoked libertarian arguments to oppose such struggles. In the post World War II period, working class demands for a National Health Service, which was eventually watered down to Medicare, were opposed by reactionary doctors’ associations, on the grounds that the reform would impinge on their “freedom” and the right of patients to choose their own doctor.

For decades a sacred cause of the far right and various libertarians was opposition to compulsory fluoridisation of the water supply—even though it massively improved the dental health of working class children, whose parents could not afford the sort of regular dental care available to the well off.

And it wasn’t just around health and safety issues that the working class movement and the left demanded “authoritarian” measures by the state to improve living conditions. Starting before World War I, there was a mass campaign centred primarily in NSW by shop assistants and their working class supporters to win early shop closing hours.

This was the pre-supermarket era, and shop assistants, who endured long, exhausting shifts of twelve to fourteen hours a day six days a week, were scattered across innumerable small shops. This meant that they were not in a strong position to win shorter hours by strike action store by store. Instead, they rallied to an eventually successful union-led political campaign demanding that state governments introduce compulsory early shop closing hours.

Petty capitalists were hysterical about this “authoritarian” restriction on their right to super-exploit their workers. In the 1960s, a few small business owners began to defy the law and illegally open up. They were hailed by the press as libertarian heroes defying the “nanny state”.

Militant workers saw things rather differently. An example I remember vividly from my childhood was the fight around weekend baking.

Baking was tough, incredibly exhausting work, especially during the summer heat. There was no air-conditioning in stiflingly hot bakeries.

After decades of campaigning, unionised bakers, like my father and his cousin, had won the legal right not to work weekends. Then, in the early 1960s, some small bakeries began to defy the law that banned weekend baking. The Victorian Liberal government turned a blind eye to these petty bourgeois law-breakers while happily arresting working class protesters. The media demanded the repeal of the law and for open slather for weekend baking, all in the name of “freedom of choice”.

But workers in the larger unionised bakeries refused to take this lying down. They rightly feared that if the small bakery owners got away with defying the law, then the large bakeries would follow suit and workers would be forced to work six nights a week or face the sack—which is exactly what eventually proved to be the case.

The bakers’ union responded by organising “flying pickets” to target the illegal bakeries. To be effective these could not be nice, friendly affairs where individual scabs were politely asked not to go in to work. They were brutal physical battles in the dark, early hours of the morning, with numerous scabs hospitalised.

My father, who had been a lightweight boxer, was in the thick of it. I well remember dad and a group of his workmates coming back home after a night of picketing on the streets of Richmond, recounting tales of chasing scabs down back alleys and dealing with them appropriately. It was a very enlightening introduction to the realities of the class struggle for an eleven year old. It led on to discussions about “compulsory unionism”, which was a hugely controversial issue in the sixties and seventies as the media championed notorious scabs, who in the name of “individual liberty” refused to join a union.

Workers in militant workplaces like the tramways had a rather different view of what liberty was. They responded to these sucks for the boss by “sending them to Coventry” (refusing any dealings with them) and demanding they be sacked. Workers also backed laws making union membership a legal requirement if you were to receive the wage increases the union won.

My father assured me that everyone in the bakery where he worked was in the union. It was axiomatic. You had to be.

Yes, but how was it enforced? What if someone did not want to join the union?

There was no problem, he kept responding. Why do you keep asking?

Until, increasingly frustrated by my repeated questioning he bluntly stated: “Well, Michael, if anyone didn’t join the union, we would beat the crap out of them in the car park after work.”

End of story. Lesson number two in the class struggle learned.

Prior to the neoliberal era, the reformist left and the broader labour movement were very much identified with demands for nationalisation of industry. Conservatives, big business interests and many small-l liberals naturally stridently campaigned against these “authoritarian” measures.

The privately owned banks mobilised a mass campaign against the Chifley Labor government’s bank nationalisation measures, claiming they would undermine consumers’ right to choose their own bank. In NSW, private trucking companies ran a campaign of defiance of the law, which guaranteed a monopoly of country freight to the state owned railways.

Arguments around freedom of choice and the ending of “authoritarian” state controls were also hauled out to justify the privatisation of electricity and gas, Telstra, the airlines, public transport, much of the health industry, and aged care, along with the running down of spending on public housing and the slashing of taxes on businesses and the rich. The success of these campaigns against “authoritarian” state controls of core public services, often disgracefully backed by Labor governments, has done nothing to advance working class interests.

Of course nationalisations and state regulation are nowhere near sufficient. They will not abolish capitalism, let alone bring about socialism. The struggle needs to go much further, and the revolutionary left has always demanded nationalisation under the democratic control of workers, not faceless bureaucrats.

Nonetheless, the demand for restrictive state measures remains a vital part of the defence of workers’ lives in the current health crisis. But we need to demand much more from governments than simply lockdowns and border closures.

For example, Schwab raised in his Crikey article the concern about border closures blocking refugees from entering Australia. To deal with this, we need to demand the building of dozens of Howard Springs-style quarantine facilities, which could safely manage the entry of many tens of thousands of refugees.

But we shouldn’t accept the claims pushed by the bosses and their lackeys that it is unacceptable “authoritarianism” to demand serious action be taken to prevent the pandemic exploding in Australia.