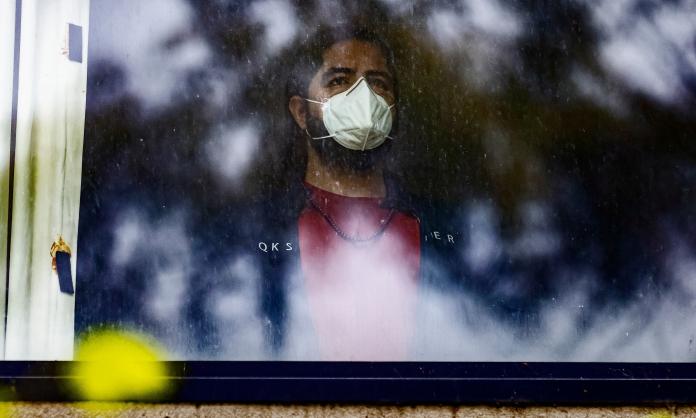

At least fifteen refugees imprisoned in Melbourne’s Park Hotel have tested positive to COVID. One has been taken to hospital. Forty-five men are held in cramped, unsafe conditions in the hotel, and no attempts have been made to evacuate or effectively quarantine any of them.

“We’re very scared here, very worried, we can’t sleep, we can’t eat”, Don Khan, 25 years old and currently imprisoned at the hotel, says over the phone. “We’re scared we’re going to die here; it’s a very bad situation for us.”

Don claims that some of the refugees are not fully vaccinated, and that they were offered a first dose only in August. The windows in the rooms were sealed shut before they arrived last December, and air is recirculated throughout the hotel. They were brought to Australia from offshore detention camps in 2019 under the Medevac health transfers—many already have underlying conditions.

Figures released to the Senate on 18 October show that vaccination rates for refugees held in detention are much lower than for the general population. As of 6 September, the date for which figures were released, 52 percent had received one dose of the vaccine, and just 17 percent were fully vaccinated. This compared to 63 percent and 39 percent for the nationwide eligible population.

Since the outbreak began, Don says, the situation has become even more difficult in the hotel prison. “We can’t go anywhere, we can’t move, can’t even get coffee.”

Conditions before the outbreak were already terrible. The men have been held in hotel prisons for two and a half years, and in offshore camps for years before that. Don was first detained on Christmas Island in 2013. He was 17 and had fled the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya in Myanmar. In 2015, he was taken to the prison camp on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island, before being transferred to Australia in 2019.

“They torture us here. But please, we are innocent people, not criminals. We are genuine refugees. But they hold us here, they torture us, what is our crime? We just want our freedom”, Don pleads over the phone.

The indefinite incarceration of refugees like Don, and the recklessness with which their health has been treated during this deadly pandemic, contradict the purported purpose of the reopening plans underway in Victoria and New South Wales. It is a cold irony that this outbreak in Park Hotel began in the week of Melbourne’s “Freedom Day”.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews grew emotional as he delivered the news that the state lockdown was ending. But he’s had nothing to say about the ongoing incarceration of these men in the middle of Melbourne and just a few kilometres from the parliament. The prime minister too never tires of talking about freedom. He has the power to grant Don his freedom, but he won’t budge.

Nor did the thousands of anti-vax demonstrators who cluttered the streets of inner Melbourne while chanting “freedom” for three days in September bother to make a pit stop outside Park Hotel. The freedoms of refugees matter little to them.

Aran Mylvaganam, founder of the Tamil Refugee Council, describes the current situation for refugees in Park Hotel as “heartbreaking”.

“They call this a hotel, but it is a prison. A private prison. People are making millions of dollars out of these men’s misery. It is a stain in the middle of our city. These men must be released.”

There are also now fears of a COVID outbreak at Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA) in Broadmeadows, a detention centre in which more than 200 refugees are imprisoned.

“We are very concerned about MITA. We’re hearing refugees there have tested positive to COVID, and everyone has been told to isolate. There are some cancer patients in that prison as well”, says Aran.

“We’re really worried about the lives of refugees in these detention centres. It’s not a safe place for them to be at this point.

“We need people to take this issue seriously, to turn out to rallies and to organise actions in their communities to get these people out. It’s desperate times.”

There are currently 1,427 refugees locked in Australian detention centres. All of their lives are at risk. Many of them have suffered years of abuse at the hands of the Australian government, Australian Border Force and various security companies. All of them should be released immediately into the community and given health care, housing and other social support.