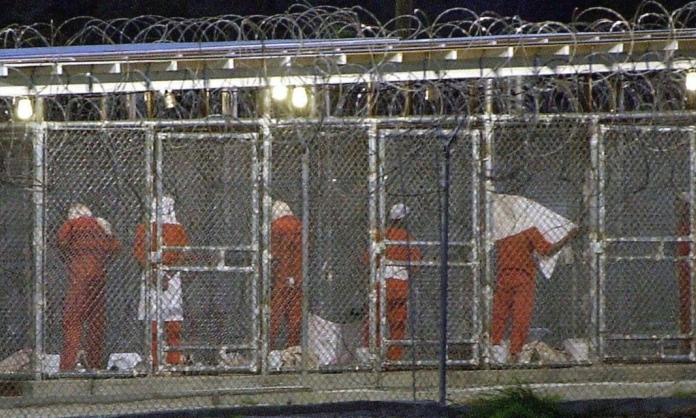

Twenty years ago this month, twenty men were unloaded off a C-141 military transport plane at the US Navy base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. They stumbled off the plane in shackles, having been chained and hooded for the duration of the twenty-hour trip from Kandahar, Afghanistan. These were the first of the roughly 800 individuals who have been held in the various prison camps of Guantánamo.

Established by the criminal Bush administration, “Gitmo” is one of the most visible edifices of the War on Terror that still is being perpetrated around the globe. Existing outside of the law, and hiding behind the manufactured category of “enemy combatant”, it has allowed the US to indefinitely imprison without trial, and to torture with impunity, anyone that it deems associated with the amorphous category of “terrorist”.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, 86 percent of all individuals were turned over to the US in Afghanistan on the promise of bounty for “turning in terrorists”. Hundreds of Afghans, Pakistanis, Arabs and Muslims were rounded up and endured years of torture that has rendered many physically, mentally, emotionally scarred, and severely traumatised.

Most of them had no, or only very tenuous connections with the organisations categorised as terrorist by the US government. Of course, a verified connection to such an organisation still doesn’t justify extrajudicial internment and torture. But the innocence of most of those who have been brutalised at Guantánamo Bay only underscores the monstrousness of the War on Terror. Even by the US government’s own metrics, it is a brutal failure: of the 800 individuals imprisoned, only eight have been “convicted” by its illegitimate military courts.

Countless books have been written about the crimes the US government committed at Guantánamo Bay. And Guantánamo is just one facility in a web of dozens of other military prisons (Bagram, Abu Ghraib, etc.) and CIA black sites in which the same unspeakable violence was inflicted on countless others.

But there is one story that has always haunted me that depicts the barbarity of the United States. In June 2006, it was reported that three men imprisoned at Gitmo had committed suicide by hanging themselves in a “suicide pact”. In an abominable display of callousness, the initial press statement by Navy Rear Admiral Harry Harris stated that not only was it a suicide but “an act of asymmetrical warfare committed on us” by individuals who “have no regard for human life”.

The military twisted three individuals taking their own lives in a six by eight foot cell, half a world away from home, into an act of warfare committed against those who were responsible for these conditions. Harris, then commander at Guantánamo, was later promoted by President Obama to command the Navy’s Pacific Fleet and then made ambassador to South Korea by Trump. He currently sits on the board of L3Harris, a military contractor.

However, in 2010, a joint Harpers/NBC news investigation uncovered that the three men had not committed suicide: they had been murdered, probably through torture, and their murder had been covered up. It appears that they were likely asphyxiated through a technique called “dry boarding” by the US military—stuffing rags in their throats while strapped in a chair. When their bodies were repatriated, it was found that the US military had removed the parts of their throats that were needed to determine the cause of death. The US took all correspondence from the three deceased men. It would later come to light that two of them were scheduled to be released.

Their names were Ali Abdullah Ahmed (also known as Salah Ahmed al-Salami), Talal al-Zahrani, and Mani Shaman al-Utaybi. Ahmed was Yemeni and al-Zahrani and al-Utaybi were Saudi. Talal al-Zahrani was captured by the US when he was sixteen years old and killed when he was 21, meaning that the period of life that his peers would spend in college he spent being tortured in extrajudicial indefinite imprisonment before he was killed and his throat torn out of his body.

Al-Utaybi was 26 when he arrived in Afghanistan—not a child like al-Zahrani, but still a young man. According to his family, he went to Afghanistan for missionary work when he was turned over to the US for a bounty. Like most Gitmo inmates, he was denied legal representation partially because he was not included on lists of “detainees” because the US kept misspelling his name.

Ali Abdullah Ahmed was 22 when he was brought to Gitmo and participated in many hunger strikes. According to the Washington Post acquisition of declassified government documents, the US military’s Criminal Investigation Task Force decided years before Ahmed’s death that he could never be prosecuted because “there was no credible information” linking Ahmed to a terrorist organisation. One can only speculate that he remained imprisoned because of his role in hunger strikes and his advocacy for the rights of his fellow inmates.

This story is but one grotesque episode in the litany of horrors of Guantánamo and sites like it around the globe. While Bush initiated the war, Obama professionalised and legalised it. Obama made a campaign promise to close the camp and in eight years did no such thing. Obama also refused to re-investigate the killing of Ahmed, al-Utaybi and al-Zahrani after the Harpers/NBC report came out. In fact, Obama released fewer individuals from Guantánamo than Bush did. Trump, of course, was Trump. Like Obama, Biden has promised to close the camp, which still holds 40 individuals, and to do so by the end of his term; but so far, he has made no movement in that direction.

Of course, shuttering Guantánamo Bay would not even begin to address the crimes that have been committed there by the US government. It would be a beginning to acknowledge those crimes, to offer an official apology and, most importantly, to pay reparations to the victims and their families. But a full reckoning would require much more, like an end to the War on Terror and US imperialism.

Today, as this dark anniversary today passes, the crimes of the War on Terror are still being committed while the wrongs remain unacknowledged, reparations unpaid.

First published at Rampantmag.com. Brian Bean is a member of the Rampant magazine editorial collective in Chicago and an editor and contributor to the book Palestine: A Socialist Introduction from Haymarket Books.