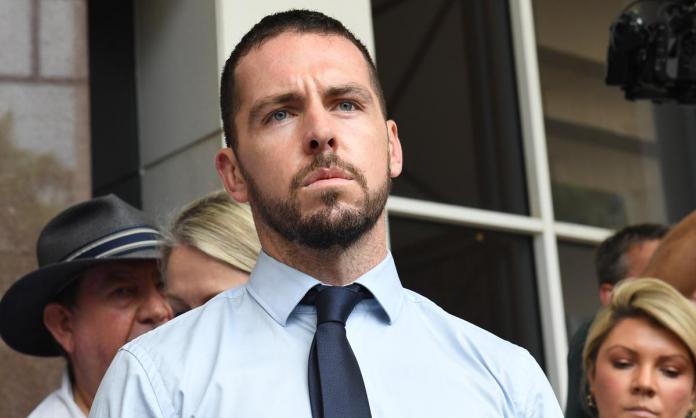

On 11 March, after a five-week trial, police constable Zachary Rolfe was found not guilty of all charges relating to the 2019 shooting death of 19-year-old Aboriginal man Kumanjayi Walker in the Northern Territory town of Yuendemu. Not guilty of murder, not guilty of manslaughter, not guilty of engaging in a violent act causing death. Not guilty of anything.

As Red Flag described at the time, Rolfe shot Walker three times during an attempted arrest and brought him to the Yuendumu police station where he and other officers “locked themselves inside with [Walker], turned out all the lights and shut off all communications with the crowd gathering outside. In front of the darkened station, Walker’s friends and relatives arrived...One of Walker’s cousins, Samara Fernandez Brown, told the ABC that she sat outside the police station for four hours. ‘We were just sitting there, and all we kept asking the constable was can you come out and let us know if he’s safe, if he’s alive’, she said. She wasn’t told until the next morning that her cousin had been killed.”

Walker’s death was not an isolated incident. As Rolfe’s trial was coming to an end in Darwin, 20 kilometres away in Palmerston another Aboriginal man was shot by police. Three months earlier, the national Aboriginal legal service had announced a grim toll: 500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had died in custody in the 30 years since the report of the royal commission into such deaths, which was supposed to make interactions between Aboriginal people and the state less lethal.

Despite their prevalence, it is extremely rare for police to be charged over the deaths of Aboriginal people. Not a single one has ever been convicted. The charging of Rolfe was supposed to achieve some measure of justice for Kumanjayi Walker and his family. Instead, it has compounded their suffering and given cover to the criminal injustice system that killed him. The lyrics of Bob Dylan’s 1964 song, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, come to mind:

In the courtroom of honor, the judge pounded his gavel

To show that all’s equal and that the courts are on the level…

And that the ladder of law has no top and no bottom.

Rolfe’s trial shows what a farce this “courtroom of honor” is. Before it had even begun, Judge John Burns, who later presided over the trial, issued 26 suppression orders, covering hundreds of pages of material. The material included text messages sent by Rolfe to friends in the army, describing Alice Springs as a “shit hole” but that “The good thing is it’s like the Wild West and fuck all the rules in the job really”, and saying that when he was deployed with the Immediate Response Team for “high risk jobs, it’s a sweet gig, just get to do cowboy stuff with no rules”.

Other suppressed material indicates that Rolfe was allegedly violent during the arrests of four Aboriginal men or boys in the two-year period before he fatally shot Walker. About eight months prior, Rolfe chased a 17-year-old Aboriginal boy in Alice Springs, who eventually gave up and lay on the ground, at which point Rolfe is alleged to have banged the boy’s head several times on a rock. He was also alleged to have falsified reports after three of these incidents, and on one occasion, after knocking out a man, was accused of asking a fellow officer to scratch him to make it appear as if he had been harmed during an arrest.

Even a local court’s 2019 judgement about a violent arrest of another Aboriginal man that Rolfe was involved in—where the judge found Rolfe had lied, that he “lacked credibility”, that parts of his evidence were “pure fabrication”—was withheld from the jury.

The prosecution argued that the material should be admitted because it indicated the tendency of Rolfe to use excessive force in arrests and then to lie in justification. But the judge decided the jury should not be made aware of this tendency.

And far from the ladder of law having “no top and no bottom”, Rolfe’s defence barrister was able to tell the jury that Walker “was dangerous, he was violent and, in many respects, he was the author of his own misfortune”. This wasn’t the only example of victim-blaming either. Murdoch’s Australian newspaper engaged in a contemptible vendetta which, as Whadjuk Noongar woman and 10 News First presenter Narelda Jacobs described, “portrayed him as an unwanted baby; as a criminal in every single thing that he did; they painted a picture of someone who deserved to be killed to justify the police actions on that day”. Yet none of this seemed to bother the judge.

Unlike Walker, Rolfe has wealthy, well-connected parents. How unlucky are those whose parents are not Canberra philanthropists, members of the Order of Australia and the kind of people who get photographed with the governor general. The infamous former SAS soldier Ben Roberts-Smith, who is facing allegations of war crimes including killing an unarmed disabled Afghan man, is also part of this charmed circle. He has been a “mentor” to Rolfe since they met in 2011. The relationship between the two was detailed in a June 2021 statement by Rolfe’s mother, Debbie, submitted to court as part of Roberts-Smith’s defamation case.

These are the people the state serves. No aspect of it is neutral—it defends the interests of those with money and power. The more you have, the more you enjoy the protection of the courts and police. And if you don’t matter, your death won’t be allowed to interfere with the career prospects of the well-connected.

In the aftermath of the case, the loudest calls are not for an overhaul of the injustice system, but for an inquiry into why Rolfe was charged in the first place. The police union in particular want to establish that the cops have the right to behave like “cowboys” and kill with impunity.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s response has been to praise the “justice system”, a system he was eager to emphasise he “respects” and “trusts” after the verdict. And rightly so: it was trusted by the likes of Morrison to ensure no-one was held responsible for the brutal death of a 19-year-old Aboriginal man. And it delivered. Just like it has so many times before.