“The physicists have known sin”, J. Robert Oppenheimer told an audience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1947. It was the turning point between World War II and the Cold War: the life-or-death struggle against fascism apparently over, the age of nuclear terror just dawning. Oppenheimer’s “sin”, and that of his peers, had been to invent the nuclear bomb and deliver it into the hands of the US military. His colleague, physicist Kenneth Bainbridge, put it more prosaically while shaking Oppenheimer’s hand moments after the first successful nuclear test: “Now we’re all sons of bitches”.

Oppenheimer’s peculiar mix of scientific genius and spiritual angst has made him a powerful literary symbol for the middle part of the twentieth century, when capitalism’s industrial and technological development blended with its drive to war, creating two abominations—the death camp and the nuclear bomb—suggesting that a complete collapse of civilisation was near. His futile post-war campaign to limit or ban the very weapon he invented has a neatly novelistic structure, perfect for a morality tale: “seeking knowledge has consequences” is one available lesson, but so is “wartime heroism requires moral sacrifice”, so both mystics and war-hawks can get some enjoyment from the fairytale.

His eventual fate—hounded out of government work after a three-week secret hearing at the height of McCarthyism, under suspicion of communist sympathies—has come to represent, for American liberals, the political right’s hysterical inability to understand geniuses with a conscience and its pathological need to brand patriotic dissent as treason. In 2022, Oppenheimer’s biographers successfully achieved his official rehabilitation: 56 years after his death, the US Department of Energy reinstated his security clearance, affirming his “loyalty and love of country”. Now, wherever his spirit may dwell, he can once more keep up with the latest developments in secret weapons technology.

Oppenheimer worked with enthusiasm and brilliance on the massive project to create and deploy nuclear weaponry. It does not call into question his moral qualms, or diminish his post-war hostility to nuclear proliferation, to note that during the war he was rather less obviously conflicted than he later claimed to have been. In the 1960s, he infamously recounted that on witnessing the first nuclear mushroom cloud he recalled the words of the Bhagavad-gita—“now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds”. But his brother, Frank, standing next to him at the time, recalled him saying: “I guess it worked”.

Otherworldly reactions to the first detonation were unsurprisingly common, and not just among eccentric Sanskrit-reading physicists. Major General Thomas F. Farrell, one of the military witnesses, wrote a report for President Harry Truman: “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately”.

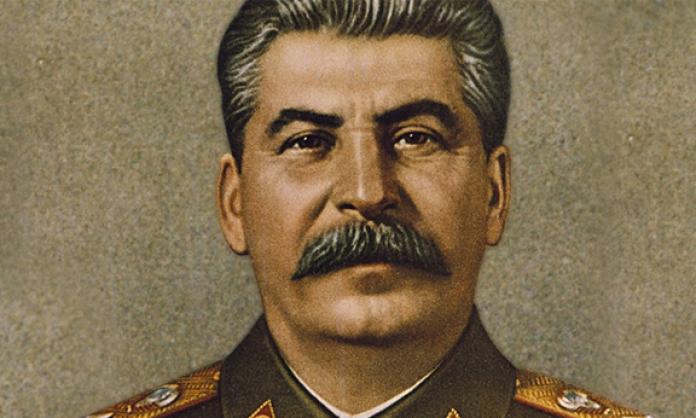

Truman himself, carving up Europe with Stalin and Churchill at the Potsdam Conference, wrote in his diary: “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world ... It may be the fire destruction prophesied in the Euphrates Valley era, after Noah and his fabulous ark”. But he also wrote: “Fini Jap”.

Likewise, after his apparently transcendental personal experience witnessing the first mushroom cloud, Oppenheimer set to work making sure it would be used in the intended manner: mass extermination. As one of the scientific representatives on the Interim Committee advising on the weapon’s application, Oppenheimer agreed that a harmless public demonstration of the weapon’s power away from human habitations would not be “sufficiently spectacular”. He signed off on the committee’s recommendation that the bomb be detonated over a factory “employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers’ homes”.

For weeks, Oppenheimer advised Farrell on how to deliver the bombs to Japanese cities—no bombing through clouds, no excessively high-altitude detonations (“or the target won’t get as much damage”). The night of the bombing of Hiroshima, he spoke to his employees in their auditorium, dramatically entering through the centre aisle past cheering crowds. Clasping his hands over his head “like a prize-fighter”, he told them that it was too early to tell the results—but “the Japanese didn’t like it”, and his one regret was that they hadn’t been able to bomb the Germans as well.

Oppenheimer was a leading figure in some of the worst atrocities of US imperialism. How could he be a secret subversive? As the FBI and McCarthy began to circle him in the late 1940s, Oppenheimer admitted that perhaps, like many, he had blundered into and out of communist-influenced milieus in the 1930s but suggested that this was an understandable mistake for a young visionary whose interests went beyond the day-to-day business of humanity. He told a credulous Time magazine that he had been “certainly one of the most unpolitical people in the world”, and in his 1954 hearings he gave evidence that until the mid-1930s, “I never read a newspaper or a current magazine like Time or Harper’s; I had no radio, no telephone ... I was interested in man and his experience; I was deeply interested in my science; but I had no understanding of the relations of man to his society.”

In the late 1930s, Oppenheimer said that a “smouldering fury about the treatment of Jews in Germany” led him briefly to engage with left-wing causes and make a few communist friends. He had liked the “new sense of companionship”, but drifted away from his new pals as he became more aware of the intellectual repression that prevailed in Stalin’s Russia. Versions of this defence were not uncommon in the terroristic atmosphere of the Red Scare: “I Was a Sucker for the Communists” was the pithy title given to the pamphlet version of blues singer Josh White’s testimony before McCarthy’s committee.

Oppenheimer’s liberal advocates have been keen to endorse the narrative that his conflicted stance on nuclear weapons represented nothing more than an individual spiritual awakening. But his friend and close colleague Robert Serber recalled that Oppenheimer’s self-mythologising as “an unworldly, withdrawn unesthetic person who didn’t know what was going on” was “exactly the opposite of what he was really like”. It is hard to determine if Oppenheimer was ever a member of the Communist Party, but he was deeply embedded in its intellectual milieus—his wife, Kitty, and his brother, Frank, were members, as were many of his mentors and protégés. He enthusiastically participated in so many communist-led campaign groups that he jokingly agreed during a 1943 security hearing that he had “probably belonged to every front organisation on the coast”. Moreover, his bloodthirsty wartime conduct was the policy line of American Stalinism.

From the mid-1930s, worldwide socialist revolution was off the agenda for Western communists. The order of the day was war. Stalin’s government directed Western communists to downplay class struggle and unite with their local capitalists in national pro-war coalitions. In the workers’ movement, once militant communist-led unions became strike-breaking patriots, pushing their members to produce maximum amounts of weaponry on minimum wages. Intellectuals like Oppenheimer, attracted to communism for its opposition to fascism, racism and inequality, were encouraged to retain their loyalty to US imperialism and to view the growing military power of the United States as a substitute for a workers’ revolution.

Robert R. Wilson, a colleague of Oppenheimer’s on the atom bomb development project, recalled: “Oppie would get a faraway look in his eyes and tell me that this war was different from any war ever fought before ... He was convinced that the war effort was a mass effort to overthrow the Nazis and upset Fascism and he talked of a people’s army and a people’s war”. Oppenheimer’s “people’s war” would end with the “sufficiently spectacular” targeted nuclear destruction of a “large number of workers” in Japan. The communist parties of the 1940s, claiming to be the inheritors of Lenin’s revolutionary anti-imperialism, celebrated this terrorism with unalloyed glee: “Jappy Ending” was how Australia’s Communist Party publication described the destruction of Hiroshima.

The invention of nuclear bombs was conducted in absolute secrecy. As the world’s greatest scientists tested the boundaries of physics, humanity’s access to knowledge was restricted and distorted so that the ruling classes would be better able to destroy the world. Stalin’s scientists deduced that a nuclear bomb was being developed when they noticed that new research on radioactive materials had suddenly disappeared from Western scientific journals. At one Tennessee laboratory, thousands of women worked monitoring and adjusting dials labelled with mysterious single letters, only to discover after the war that they had been enriching uranium for the bomb.

Oppenheimer hoped that, after the war, the US would be transparent about its nuclear technology, that open discussion would lead to international cooperation, that the bomb could be restrained or banned, and that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be one-offs. His bureaucratic rivals, particularly the hawks of the US Air Force, pushed for the development of new fusion bombs that could kill tens of millions, and their deployment on long-range bombers. This dispute is probably what put a target on Oppenheimer’s back and led to his persecution.

American liberals look back on McCarthyism as a national shame. But it did the job: the war machine prevailed, secrecy and nuclear proliferation defined the ensuing decades, and now none of us knows how many nuclear weapons exist in the world, who controls them, how powerful they are or where they are targeted. At this very moment, some modern-day Interim Committee may be determining that our homes are “sufficiently spectacular” targets for their latest invention.

Oppenheimer, like many other Stalinists and fellow travellers, used the language of socialism and anti-fascism to justify some of the worst crimes of the US empire. “He wanted to be on good terms with the Washington generals”, his colleague Freeman Dyson observed, “and to be a savior of humanity at the same time”. For a few years, American “communism” taught its followers that it was possible to do both: that peace, freedom and human development could be served by the accumulation of military might in the hands of our rulers. We live in the shadow of that lie to this day.