A newspaper reports that trade unionism in Sydney is “virtually dead”. An “Old Unionist” writes to the Sydney Morning Herald, remarking that “trades unionism at the present time is almost a thing of the past, caused principally by the introduction of machinery”.

The story is no better in other parts of the country. A correspondent from Tasmania writes: “[T]here seems to be a total absence of organisation and little or no unionism”.

Our movement is a fraction of its former size. Plenty of people are writing us off. The year is 1899. Things had been so different just a decade earlier. In 1890, unions covered 21.5 percent of the workforce in New South Wales – the highest union density in the world at that time.

This rising power was intolerable to Australia’s rulers. From 1890, key unions were smashed in a series of colossal industrial battles. The waterfront and seafarers’ unions, metal miners at Broken Hill, coalminers and shearers – all went down to defeat. A devastating economic depression and drought further weakened the power of unions, especially in the key commodity and transport sectors.

In 1891, the Sydney Trades and Labor Council had 81 affiliated unions with more than 41,000 members. By 1899, this had shrunk to eight affiliates with just 401 financial members – a decline of 99 percent. Some unions, like the stonemasons, previously a key pacesetting union but under threat from technological change, were crushed and never recovered their former strength.

The 1900s

The union movement as a whole, however, did recover – spectacularly. By 1913, New South Wales again had the highest union density in the world, with around 50 percent of workers in unions. As with any important event, there’s controversy about which factors were crucial in this revival.

One widely told version gives a central role to Australia’s arbitration system. The working class, it is argued, was defeated in industrial battle in the 1890s and therefore wisely turned to political action instead. The new Labor Party, along with progressive liberal politicians, passed the NSW Conciliation and Arbitration Act of 1901, followed by a similar federal law in 1904. Unions formed (or reformed) to take advantage of these new legal opportunities. Arbitration courts made awards that granted union preference in hiring, and the Australian union movement was reborn.

This reading of history gives much support to those in our movement who, like Sally McManus, see bolstering the powers of the Fair Work Commission as the crucial task for unionists today. But it’s a dishonest account of the role of arbitration, and doesn’t explain the union revival of this era.

For starters, the arbitration mechanism was not fit for purpose. Coalminers, unlike many workers, were initially strong supporters of arbitration. But employer legal challenges reduced the powers of the NSW arbitration court to almost zero by 1906. Even worse: awards of the court applied only to union members, giving employers a powerful incentive to sack unionists.

Even when these legal obstacles were overcome, historians Rae Cooper and Ray Markey point out that arbitration very often only ratified what had already been won through organising and industrial action. Former union official Michael Crosby draws on these studies in his book Power at Work to argue that the surge in unionism in the early 1900s “had little to do with arbitration and far more to do with the strategies and tactics used by the workers themselves to get collective power”.

These writers focus on the activities of the Organising Committee of the NSW Labor Council. This body played a role in organising important unions in the years before the great confrontations of the early 1890s, and was crucial in the union revival.

Between 1902 and 1907, the Organising Committee assisted 54 groups of workers to organise – helping with registration and negotiations, the production of handbills, resources for organising drives and other essentials. In 1905 it convened a conference to discuss unionism among women workers, helping to organise women workers in box manufacturing, clubs and restaurants, laundries and bookbinding.

These writings are an advance on the “rising tide of arbitration” school of history. They recover one basic, crucial fact: there is nothing inevitable about a union revival, even when (supposedly) aided by a relatively favourable legal regime. Unionism does not simply rise and fall like the tides: unions are revived by people who set out deliberately to revive them by organising workers.

However, these histories downplay some vital ingredients in any union revival.

For one, strikes. It wasn’t just organising for the sake of organising that brought results – it was organising for industrial action. Michael Crosby’s account of this union revival is strangely lacking references to industrial action.

It has no mention of the first strike on the Victorian railways in 1903, or the 70-week coal lockout in Victoria from January 1903, or the four-month strike in Broken Hill (followed by an extended lockout for some workers) and the 18-week strike in the NSW coal industry in 1909, or the Brisbane general strike of 1912.

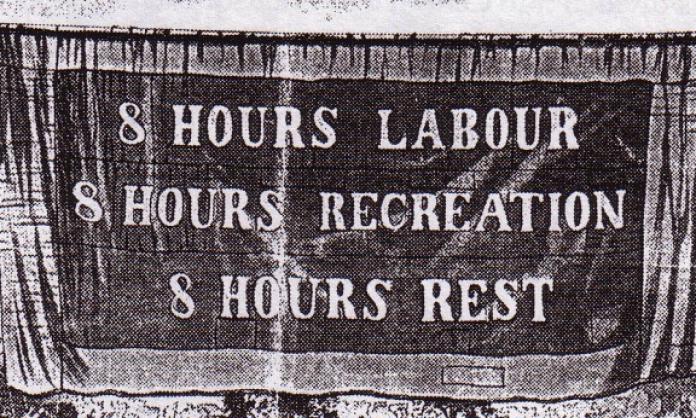

Many strikes ended in defeat, but were crucial to the union movement’s subsequent advance. The 1909 NSW coal strike went down to defeat, the miners isolated and their militant leader, Peter Bowling, jailed. But straight after the strike, the miners were awarded the eight-hour day for the first time. It was militant action outside the arbitration system that forced some concessions from this system.

For the workers involved, strikes also provided a practical education in what was needed to win. Broken Hill miners only fought BHP to a draw in the brutal dispute of 1909. But this laid the basis for their spectacular, hard-fought victories that pioneered the 44-hour week during World War One, and the 18-month “big strike” following the war that won the 35-hour week.

The other factor downplayed in these histories is radical politics. In 1908 the most important union – the coalminers, whose labour powered the entire industrial economy – adopted the preamble of the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World as their own: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common … Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organise as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth”.

Not every leader of the union revival was a revolutionary; Labor politician Billy Hughes, for instance, played a key role in reforming the Waterside Workers Federation in Sydney at the end of the 1890s. But socialists and militants of various descriptions played a disproportionate role in the union revival of this period – especially the syndicalists, revolutionary industrial unionists.

The attitude of these militants to arbitration was summed up by the great syndicalist agitator Tom Mann: “The Labour Parties pinned their faith to Arbitration Acts … After being for a time favourably disposed towards them, I have been compelled to definitely declare that such measures are a most serious impediment to working-class solidarity; a powerful agency for hypnotising the workers into somnolence, that makes them strangers to the CLASS WAR … that gives the capitalist judiciary complete control of the men in the workshops, mines, mills, and factories ... and hands the workers over – handcuffed and ankle-chained – to the capitalist bosses, so that verily their last state is worse than the first”.

Views like this were widespread enough, especially in key strategic sections of the working class, to pose a serious challenge to the strategy of voting Labor and waiting for arbitration. Activists with a clear class analysis, confidence that their fellow workers could make history and a healthy contempt for capitalist law were crucial in pushing the class struggle past the limits accepted by existing labour movement leaderships.

The 1930s

The three elements crucial to union revival in the 1900s – a methodical approach to organising workers, a focus on serious industrial action and activists informed by revolutionary politics – were also crucial in the union revival of the middle and late 1930s.

Unions were overwhelmed by the Great Depression. As Australia tipped into depression in 1928-29, 20,000 timber workers went down to defeat in a five-month strike in Victoria and NSW; waterside workers fought and lost a desperate rearguard action against wage cutting; and on the northern NSW coalfields, 10,000 coalminers and their families endured a 16-month lockout, only to be defeated when the new Labor government refused to enforce the law against the coal owners’ lockout.

The revival came first in coal. Communist activists in the Victorian mining town of Wonthaggi spent months preparing for a strike in 1934. There were 140 members of the Militant Minority committee in the town, a Communist-backed organisation that promoted union militancy and connections across the class.

Under the slogan of “make every member an activist”, committees were organised for everything from food, entertainment and propaganda, through to barbering and shoe repair. A well-organised women’s auxiliary cut against the isolation and hardships of a long strike. The strike as a whole was coordinated by a “broad committee” involving dozens of rank and file leaders as well as the union executive.

This high level of rank and file organisation underpinned a solid five-month strike by 1,300 miners, which slowly developed into a cause célèbre in the union movement. Eventually, faced with the prospect of solidarity strikes, the Victorian government headed by Robert Menzies caved in, awarding union recognition and reinstatement of victimised miners.

This victory turned the tide. Within two years, miners inspired by this win (many of them associated with the Communist Party) had won leading positions in the coalminers’ union. Using the same approach involving careful preparation and mass participation, the union launched a six-week national coal strike in 1939.

The strike was a huge breakthrough, winning a 40-hour week, 10 days’ annual leave, measures for the suppression of coal dust and increased wages. Though the fruits of the victory took three years to flow through, historian Robin Gollan argues that “in total the changes were the greatest ever made to the advantage of the workers in the mining or any other industry”.

By this time a broad union revival was well under way. Militants steeled in the struggles of unemployed workers in the early 1930s pushed their unions on a militant course as the economy slowly revived.

Jim Munro was a veteran of this movement. Recruited to the Communist Party in 1931, he spent the early depression years organising unemployed workers to fight off police and bailiffs in battles against eviction, to demonstrate to win dole payments and to strike for better pay on relief projects. Years later, he told an interviewer how political contacts became involved in industrial work:

“It all came from work down on the job, among the rank and file … When you sold a paper to a person a few times, when they became a regular customer, you were friendly with them. You found out their address, their name, where they worked, if they were in a union or anything, and we used to turn their name into the centre.

“And then they used to be approached by people in their own industry. So you were working in a timber factory and all of a sudden a bloke turns up one night to see you. He says ‘I heard a little bit about you, you’re a good chap where you work. I work in the timber industry, we’re trying to get a bit of a committee together to shake the officials up about so and so.’

“And they’d have a meeting. And before you knew where you were, you’d have a group, you’d have a minority movement in that particular union …

“When things started to pick up a little bit, and a few jobs started to appear, these people who had been educated in the unemployed [movement] started to go back into industry. Straight away, there was a change inside the trade union movement.”

There were enormous problems with the Communist Party at this time. The growing Stalinism of the world Communist movement swung parties from rigid sectarianism in the early 1930s to enforcing class peace by the 1940s.

Nevertheless, these militants got enough right to play an important role in rebuilding the union movement from a catastrophic situation.

The 1960s

An explosion of militancy followed the Second World War. But by 1950, unions were on the back foot again. The deepening Cold War led to the isolation of an ossified Communist leadership in many unions.

There were also the “penal powers”, introduced by the Chifley Labor government in 1948 and massively expanded by the Menzies Liberal government following their 1949 election win. These imposed massive fines for industrial action, with the aim of forcing the unions themselves to discipline workers. They were effective: the postwar rate of strikes fell by more than 80 percent by the early 1960s.

The recovery came in fits and starts. For the first time, significant strikes among production workers hit the car plants in 1962, 1963 and 1964. An eight-month strike at the giant Mount Isa mine was defeated in 1964, but industrial struggle was on the map again.

Finally the rolling, nationwide, week-long general strike of May 1969 that freed jailed union leader Clarrie O’Shea smashed the penal powers: employers were now too terrified to use them. A colossal strike wave resulted, winning average real wage increases of 30 percent between 1970 and 1975. Conditions like four weeks’ annual leave, workers’ compensation and the principle of equal pay for women were won in this period.

Once again, this industrial revival was intertwined with a widespread political radicalisation. The movement against Australia’s war in Vietnam was radicalising many thousands of young people and pulling the whole of society to the left. The newspapers in the lead-up to the O’Shea strike reported students being sent to prison for handing out anti-conscription leaflets in the streets of Melbourne. Defiance was in the air.

Socialist historian Tom Bramble, in his book Trade Unionism in Australia: a History from Flood to Ebb Tide, quotes Brisbane boilermaker Jim Craig from this period: “The sooner the trade union movement takes a leaf from the students and youth in their actions for civil liberties and anti-draft actions, the better – if it’s a bad law, defy it; and the sooner we start publicly burning [anti-strike] court orders, as the kids burn their draft cards, the better”.

Radicalised students also had a big impact on unions when they joined the workforce, transforming formerly staid white collar unions such as teachers and insurance workers into combative industrial unions for the first time.

A fourth union revival?

History moves in waves, not just long flat lines. We have no way of telling when the next wave will break: when the hard slog of building union strength wherever we are will suddenly shift, like US teachers’ struggles this year, into a wave of strikes. We don’t know when a wave of struggles, intertwined with a political radicalisation, will fundamentally remake the terrain of working class struggle like the three union revivals we’ve seen since 1900.

But history tells us that every advance we make for radical political forces, as well as for union forces serious about systematic organisation and industrial action, will have a crucial role in the struggles to come.