At nine o’clock one night in September 1920, three men were spotted prowling around one of the biggest auto factories in Turin, in Italy’s north. The factory had been occupied by workers, and three armed worker-guards approached the men. Giovanni Parodi, one of the leaders of the Italian workers’ movement, recalled the exchange that followed:

“What are you doing here?”

"Oh, we just wanted to see what work you were doing,” the intruders responded.

“Oh, you want to see what work we’re doing?” said the worker-guards. “Come along in!”

The three intruders protested, but they were carried inside and searched. Workers found the men to be festooned in revolvers and belts of ammunition like a combat squad. They were company spies, sent by employers desperate to wrest back control of their factories.

“Now then,” said their captors, “if you want to see what work we do, you’d better come and work with the workers.” The three spies were marched to the furnaces. They yelled that the metal was scorching. The workers replied: "For us, it burns all our lives. For you it’s burning only tonight, so get on with it.” On the face of the furnace someone had inscribed “Labour is Noble.”

The Biennio Rosso, or “Two Red Years” in Italy from 1919-1920, were a key link in the chain of world revolution after the First World War. A mass workers’ movement in the northern industrial centres attempted to launch a decisive struggle against the capitalist class. In the rural south, land occupations by peasants upended centuries-old social relations.

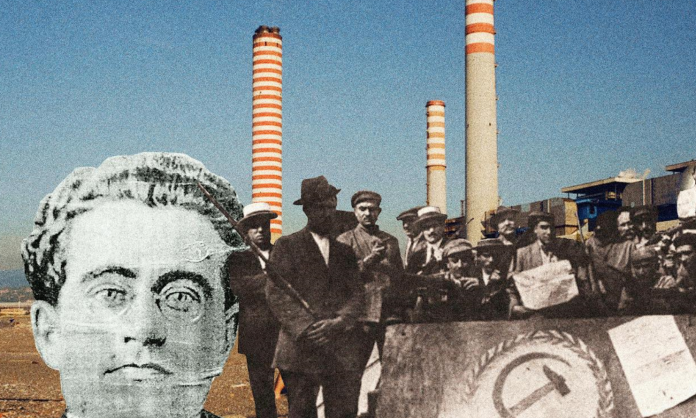

The radical conjuncture created by war and social upheaval gave Marxist activists an unprecedented opportunity to relate their theory to working class practice. Revolutionary workers attempted to assimilate the experience of the Russian Revolution by seizing control of their factories and building their own institutions of self-government. Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci played a unique role in this process, developing a theory of revolution side by side with workers fighting for their emancipation.

The revolutionary experiment in Italy was a beacon for the socialist movement internationally, but it tragically failed to deal capitalism its death blow. The movement’s failure would have severe consequences. Only three years after the height of revolutionary hope, the first fascist regime in history would come to power in Italy as revenge for a revolution half-made. For Gramsci, and socialists who studied these events from across the world, decisive lessons in revolutionary strategy were derived from the experience.

The life of Antonio Gramsci

Gramsci was born on the southern Italian island of Sardinia, one of the most economically underdeveloped areas in the country. His early politics were a combination of class hatred and southern nationalism. He later recalled:

What spared me from becoming a completely lifeless rag? The rebellious instinct I felt against the rich as a young boy… This instinct extended to all the rich who oppressed Sardinian peasants, and so then I thought it was necessary to fight for the national independence of the region: ‘Throw the continentals to the sea!’ How often I repeated those words.

Gramsci’s first serious introduction to socialist politics came when he received a scholarship to the University of Turin in 1911, where he studied alongside other future leaders of the Italian Communist Party. However, it was not the intellectual atmosphere of the university that had a transformative impact on Gramsci’s ideas, but the political climate of Turin. Located in the industrial north, Turin was the Italian Petrograd, the epitome of the proletarian city. The development of the auto industry in Turin turned it into a centre of militancy. Already, it had seen general strikes in 1902, 1904, 1907, and 1909.

Gramsci joined the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) in 1914. True to the tradition of parties of the Second International, it was a broad socialist organisation. It incorporated both reformists, who looked to the state to lead a legal transition to socialism, and Marxist revolutionaries who wanted to overthrow it.

The openly reformist wing was led by Filippo Turati. Numerically they were a minority in the party, but strongly implanted in a series of key bureaucratic institutions: the PSI’s parliamentary grouping, which by 1913 had 52 elected deputies in the parliament; the town councils; and the trade unions. This gave the reformists a political influence disproportionate to their numerical strength in the party.

The "Maximalists”, led by Giacinto Menotti Serrati, dominated the party leadership. Serrati’s group criticised the reformists from an apparently radical Marxist position. In practice, however, they failed to distinguish themselves from the reformists, focusing on agitation for democratic reforms and pouring endless energy into election campaigns.

Lastly, the revolutionary wing was centred around Amadeo Bordiga, a young radical from Naples. Bordiga’s hostility to the reformists in the party and his opposition to Italian imperialism gave him credibility with radicals and youth. He would become notorious for his argument that revolutionaries should abstain from bourgeois elections as a question of principle, earning his faction the nickname "Abstentionists”. But Bordiga was much better at denouncing the right within the PSI than at building revolutionary leadership out of existing struggles.

The PSI stood virtually alone among the major parties of the Second International in its refusal to back the First World War. The party played a crucial role in establishing the Zimmerwald conference of antiwar socialists. Serrati personally risked jail by defying the censors and publishing Zimmerwald’s manifesto in Avanti!, the party’s daily paper.

But the principled rhetoric of the party served to obscure its fundamentally passive attitude to the war in practice, summed up by their slogan “neither support nor sabotage.” The PSI would not actively mobilise the working class for the war effort, but neither would they pledge to disrupt it through strikes, protest, or revolution.

As one article put it in Avanti!: “Study, yes, for today we can collect the materials necessary for action tomorrow. But action today, on concrete and immediate questions? No, no, no!”

Italy would not enter the war until 1915, and so a major confrontation between revolutionary and reformist forces within the party was forestalled. A position of calculated ambiguity could prevail, holding these forces together. It was not long, however, before the war arrived and changed everything.

War and revolution

The First World War was profoundly unpopular in Italy. At the front, at least 615,000 Italians were killed, half a million disabled and a million wounded. Forced to risk their lives for scraps of territory they’d never heard of, peasant conscript soldiers returned to Italy radicalised. The police shot three anti-militarist demonstrators in June of 1914, sparking an insurrection in Ancona. Factory workers chafed against the establishment of martial law in the factories. The working class expanded rapidly as the drive to increase war production proceeded. When the hothouse atmosphere created by the war was combined with news of the outbreak of revolution in Russia, tensions within the socialist movement reached new heights.

The reformist wing of the PSI hailed US President Woodrow Wilson’s diplomatic efforts for a resolution of military conflict, rather than looking to mass working-class action. As nationalist fervour raised its head, the reformist Turati came out openly in support of the war effort.

Meanwhile, the reality of revolution encouraged the radicals. The Russian Revolution was greeted with more enthusiasm in Italy than anywhere else in the world. In August 1917, an official delegation of Russian reformist socialists was sent to Italy to secure international support for the ruling Provisional Government. To their dismay, wherever they went, they were received by enthusiastic mass audiences chanting “Viva Lenin!”. Serrati rushed to affiliate the PSI to the Communist International, the new centre of world revolution established by the Russian Bolsheviks. The PSI was the first mass party to join.

The polarisation paralysed the PSI. This was no more evident than in the monumental riots of August 1917. Workers walked out on strike when bakeries failed to open due to supply shortages. One account recalls workers marching out on strike proclaiming “We can’t work, we want bread.” The manager of the firm replied "Of course, how can anyone work without eating!”, and announced he was telephoning military supplies to bring a truck full of food. The workers collectively paused, looked one another in the eyes, as if gauging each person’s opinion, and then cried out in unison “We couldn’t care a damn about bread! We want peace! Down with the profiteers! Down with the war!”

The August events were a consciously anti-war insurrectionary movement. Some participants likened it to the February revolution in Russia. Women and youth played a central role in leading demonstrations and agitating for troops not to fire on their brothers and sisters. The PSI blinked, and abdicated leadership of the movement. Without any direction, it was tragically contained in Turin, and suppressed with brute force. Over 50 were killed, 1,500 arrested, and 1,000 of the most militant workers conscripted to fight at the front.

For all their differences, all wings of the PSI were passive. The reformist Turati justified incorporation into the state and collaboration with employers. Every new electoral gain, every new contract signed with employers heralded another step toward socialism. The ostensibly more radical Serrati asserted “Marxists do not make history, we interpret it”: revolutionary rhetoric could be combined with passivity in practice.

Bordiga tended to recreate the same logic. He argued that the most important task was for revolutionaries to maintain a ‘“pure” political line, avoid involvement in day-to-day struggles, and hold faith that the future revolution would sweep revolutionaries like himself into the leadership of the workers’ movement. He had no interest in winning over workers who hadn’t broken completely with a reformist strategy.

By 1919, Italy was caught in a “strike frenzy”. Protests against price hikes in La Spezia escalated into an insurrectionary uprising in June. Local government collapsed and power temporarily passed into the hands of workers’ committees. In a country marked by periods of intense militancy, there was no organised revolutionary tendency that could grasp the link between existing struggles and the objective of working class revolution.

Workers’ democracy

Antonio Gramsci had come to prominence in the Turinese labour movement in traumatic circumstances. The repression of the August bread riots saw virtually the entire local leadership of the PSI jailed, and Gramsci was made editor and sole journalist of the party’s local paper. His first piece, written in August of 1917, hailed the still-unfolding Russian revolution as a proletarian act that opened up the historical possibility of socialism.

Gramsci’s politics in this period contained a streak of voluntarism, the belief that revolution could be made as an act of will. In 1917 he wrote: “The Bolshevik revolution is based more on ideology than actual events... The Bolsheviks renounce Karl Marx and they assert, through their clear statement of action, through what they have achieved, that the laws of historical materialism are not as set in stone, as one may think, or one may have thought previously.”

Whilst somewhat crude, Gramsci’s formulation was a reaction against the stifling determinism that infected so much of the PSI. Gramsci’s burning imperative was to find a means to translate the revolutionary energy of Russia into a roadmap for international revolution through proletarian self-activity.

In the pages of his journal, L’Ordine Nuovo, Gramsci began to sketch the outlines of a strategy for workers’ power. In the article “Workers’ Democracy”, published during the strike wave of June 1919, Gramsci asked: "How to harness the immense social forces unleashed by the war? How to discipline them, give them a political form capable of growing and developing continuously into the skeleton of a socialist state which will incarnate the dictatorship of the proletariat?”

This was the beginning of Gramsci’s agitation for the creation of soviets, the novel form of democracy invented by the Russian working class. The formation of soviets was a popular slogan amongst revolutionaries in Turin. Gramsci’s originality lay in his strategy for building these institutions out of existing struggles.

Gramsci was not an aloof academic philosopher: his theory of social change was not plucked from thin air. It was an attempt to synthesise the experience not only of Russian soviets, but also the British shop stewards' movement, and the Hungarian and German Revolutions.

Gramsci argued that the socialist state “already exists potentially in the institutions of social life characteristic of the exploited working class… The internal commissions are organs of workers’ democracy which must be freed from the limitations imposed on them by management, and infused with new life and energy.” The internal commissions in the factories were analogous to shop stewards’ committees, with rank-and-file workers representing themselves against the bosses. Gramsci now said they had to extend beyond their traditional role of mediating industrial disputes and assert workers’ control over production. Mirroring the arguments in Lenin’s State and Revolution, Gramsci envisioned this network of workers’ councils as a “magnificent school of political and administrative experience”, a means for workers to prepare themselves to build a new society.

Gramsci’s proposals had an electrifying impact. In August, the workers’ representatives at FIAT-Centro, the largest factory in the country, dissolved the internal commission and called for the election of a council. Workers at FIAT-Brevetti developed the models: only union members could stand for election, but all workers were given a vote. The councils were independent of official union structures, and aspired to embrace the entirety of the working class. By October 26, more than 50,000 were organised in councils across Turin, by the end of the year more than 150,000. In a speech to council leaders in September, Gramsci explained why L’Ordine Nuovo’s proposals had such resonance:

We know that our journal has contributed not little to this movement… We also know, however, that our work has had a value only insofar as it satisfied a need, helped to make concrete an aspiration that was latent in the consciousness of the labouring masses.

The internal commissions, which laid the basis for factory councils, were a space long contested between the rank-and-file and conservative trade union officials. The majority of officials had sided with the state and were attempting to assist in imposing military discipline in the factories. Gramsci’s intervention gave a programme and strategy to a rank-and-file fighting for greater control in the context of war and economic crisis.

The council delegates drew up a programme bearing the mark of Gramsci and L’Ordine Nuovo’s influence. The programme declared itself “an exposition of the concepts which underpin the rise of a new form of proletarian power… Its purpose... Is to set in train in Italy a practical experiment in the achievement of communist society.”

A proletarian state?

While the programme of the councils expressed the highest aspirations, they never reached the level of asserting an alternative political authority to the capitalist state. They remained largely restricted to the task of asserting control over production on the factory floor.

At times, the intervention of the L’Ordine Nuovo group could reinforce the illusion, widespread amongst council participants, that controlling production was enough to challenge the capitalist class for power. They wrote: “The council is an historical product of Italian society, defined by the necessity to dominate the productive apparatus, born of the conquest of self-consciousness by the producers.”

The Italian working class had made historic strides towards controlling their own destiny. But while private property prevailed and political power remained in the hands of the capitalist state, it was impossible for workers to liberate themselves completely. The council had to be extended, like the soviets in Russia, to encompass political as well as industrial organisation.

Attempting to assert control of production could exert contradictory pressures on the working class. One the one hand, it could advance the struggle by impressing upon them the need to take control of the broader administration of society and fight for political power. On the other hand, it could lead workers down the dead-end of advising management on how to improve production.

This danger was evident when the bosses at FIAT demanded productivity be increased to compete with American output levels. The rank-and-file reflexively rejected this proposal and a series of mass meetings angrily denounced them. But they were calmed by Boero and Garino, two leaders of the council movement. Boero and Garino argued that the power of the working class grew from their mastery of production, and so they couldn’t refuse attempts to increase output. But, even with councils running the factory floor, these increases in productivity would still flow to the bosses in the form of profits. Boero and Garino couldn’t grasp these implications. Their response was based on a romantic conception of a future socialist society where workers controlled the fruits of their labour. As things stood, the council leaders were unwittingly holding back an incipient strike movement against capitalist profiteering.

By March of 1920, Gramsci was developing a programme to overcome the limitations of industrial organising. In Avanti! he outlined the immediate tasks of the councils as: "1) solving the problem of arming the proletariat 2) arousing through the province a powerful class movement of poor peasants and small-holders in solidarity with the industrial movement."

It became increasingly clear to Gramsci that this task could not be accomplished by a journal like L’Ordine Nuovo. To build the councils into institutions capable of contesting for power, a cohered national organisation of militants was needed, a revolutionary party committed to leading the struggle to its conclusion.

Read part two of this series.