Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities lived in Eastern Europe for hundreds of years among other populations which had not yet fully established modern nation states, creating a web of tensions and conflicts. Denied the legal right to own agricultural land until the 19th century, Jews concentrated in towns where exclusion from many economic fields led to a restricted range of occupations. The resulting competition laid the basis for hostility among ordinary people. At the top end of the class structure, Jews historically played particularly important roles in finance and trade and owned between 60 and 90 percent of Poland’s banks by the end of the 19th century.

With the urbanisation of the 19th and 20th centuries, the primarily religious Jewish communities of the Middle Ages were secularised and exposed to the phenomena associated with the rise of capitalism – the mass market and the rise of the industrial working class. They organised into trade unions very early compared to other workers in the region, beginning in the 1890s in the area of the Russian Empire to which they were restricted. An area of about 20 percent of the territory of European Russia known as the Pale of Settlement, this included much of present day Lithuania, Belarus, Poland and Ukraine, and ended only with the Russian Revolution in 1917. Beginning in the 19th century, Jews in these areas were regularly subjected to large-scale, targeted and repeated anti-Semitic riots known as pogroms.

In 1938, there were 98,000 members of Jewish trade unions in Poland. In the inter-war period, half the workforce in Poland was made up of self-employed craftsmen such as tailors and watchmakers. Jewish industrialists were reluctant to employ Jewish labour and put their class interests first, even amid the increasing anti-Semitism and high unemployment of the late 1930s.

Thus Jews in Eastern Europe were divided by class, but the divisions were distorted by historical restrictions and repression. The relatively large proportion of the Jewish bourgeoisie in finance and trade appeared to the popular imagination as a global conspiracy. The relatively strong socialist and trade union ideas among the working class provided grist to anti-Communist right wing nationalists.

In the 1920s, there were approximately 2.8 million Jews in Poland, 10.5 percent of the population. There were three main political currents. On the right was Agudas Yisrael, the party of traditional orthodoxy, supported by about one-third of the community. They supported any regime that did not interfere with their religious activities. Although there were Jews in the Communist Party and the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS), the main left wing Jewish party was the Jewish Labour Bund, numerically smaller than the Zionists until the mid-1930s, but dominant among the Jewish working class. The third political current, Zionism, was strong enough to send representatives to parliament in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. But its local base must be seen in the international context.

The Zionists have historically had a peculiar relationship with the imperialist powers. In the period before the Second World War, most countries fell into one of two camps. On the one side were the major imperial powers (the US, Britain and the Soviet Union) together with smaller imperialists and colonial settler states (Australia and South Africa). On the other side were countries which had been occupied as colonies, in which anti-imperialist nationalist struggles occurred. Zionism was a political project without a national base but with nationalist aspirations. However, unlike the colonial-based nationalist movements, and despite the position of Jews as an oppressed group, at no point did the Zionists side with the anti-imperialist camp. From the very beginning, their strategic orientation was geared to winning support for their project of establishing a state from the major imperialist powers.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries they targeted the German kaiser, the Russian tsar, the sultan of Turkey and the Austrian Habsburgs, despite their professed and active anti-Semitism. During the First World War, most Zionists were pro-German (due to the extreme anti-Semitism of the tsarist regime), but established an alliance with British imperialism in the form of the Balfour Declaration in 1917. Britain’s nominal support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine was purely propaganda; it had no power to act. But the Zionists were encouraged in their orientation to imperialist powers. Notoriously, Zionists offered themselves to the British as imperialist agents in the Middle East, where they sought to form, in the words of Zionist leader Theodore Herzl, “an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism”.

The Zionists soon found that support was offered only insofar as it suited the interests of imperialism. The period after Hitler came to power in 1933 was marked by increasingly virulent attacks on Jews. In 1938, US president Franklin Roosevelt initiated a conference at Evian-les-Bains, France, supposedly to help Jewish refugees. At that time, about 450,000 Jews had left Germany out of a total of 950,000. But the conference did nothing. The US delegates offered no place to settle Jews fleeing Hitler and passed the buck to the South American states. One by one, the South Americans said no. The Australian representative announced: “[A]s we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one”. Genocide against Aborigines and the White Australia immigration policies went unremarked.

The outbreak of war did not change the attitude of the imperialist powers. When Jan Karski, a Polish resistance fighter, escaped to the West, he brought detailed information about the situation, including the Holocaust. Karski met political leaders including the UK foreign secretary Anthony Eden and president Roosevelt. None of the political leaders took him seriously. Roosevelt reportedly asked about the condition of horses in Poland but did not ask a single question about Jews. Karski concluded that the Jews “were abandoned by all world governments”.

Beginning around March 1943, there were calls for the Allies to bomb the rails leading to the Auschwitz death camp. US military chiefs refused, arguing that this would divert resources from the war effort and that rail lines were hard to hit. Undersecretary of war John J. McCloy fretted that such bombings might “provoke more vindictive actions by the Germans” – as if there was any worse fate than the death camps. According to historian Louise London, the tone of Allied refugee policy was set by the US, but Britain followed closely behind, “putting self-interest first”.

Western governments displayed a shocking indifference to the fate of the Jews. Historian Walter Laqueur concluded that, despite knowing about the “final solution” from an early date, the US, the UK and the Soviet Union showed no interest in the fate of the Jews; he argues that, not only was no action taken, but the information was actively suppressed. US intelligence, for example, took an interest in the movements of forced labour teams because they were a factor in the German war effort. But according to Richard Breitman in US Intelligence and the Nazis, the CIA’s predecessor organisation, the Office of Strategic Services “does not seem to have taken much detailed interest in German camps as they concerned the extermination of Jews”. Michael Neufeld, introducing a collection of essays on prospects for bombing Auschwitz, concludes: “The Holocaust simply was not an important issue on the public or military agenda of World War II”.

There was never a real prospect that the imperialist powers before the war, or the Allies and the official war effort, would help Jews. Throughout the whole period, however, Zionism never swerved from its orientation to imperialism. The organisationally independent right wing of the Zionist movement, known as the Revisionists, had such active relations with the Italian Fascists in the 1930s that Mussolini praised them: “For Zionism to succeed you need to have a Jewish state, with a Jewish flag and a Jewish language. The person who really understands that is your fascist, Jabotinsky”.

The German Zionists actively collaborated with the Nazis in the 1930s, breaking the international boycott on German goods and transferring capital to Palestine in a deal known as the Ha’avera (Transfer) Agreement. Some 60 percent of all capital invested in Palestine between 1933 and 1939 was channelled this way.

Their fundamental orientation to imperialism critically weakened the Zionists once they were confronted with the Holocaust. They were used to accommodating local and international powers. They were accustomed to relying on others and on wheeling and dealing. They were experts at behind the scenes manoeuvres and manipulations. And they were practised at turning a blind eye to the anti-Semitic beliefs and actions of those with whom they were negotiating.

The focus for all Zionist factions was always the promotion of emigration to Palestine, not action to resist growing anti-Semitism. Consequently, support for Zionism among Polish Jews declined during the 1930s. As the slogan of the right wingers and anti-Semites was “Kikes to Palestine”, Zionists who made the same argument (although with more refined language) had some difficulty distinguishing their politics. Zionist politics was hamstrung.

‘IT’S BURNING, BROTHERS, IT’S BURNING!’

In May 1926, marshal Joseph Pilsudski took power in Poland through a military coup. Although a reactionary right winger, Pilsudski was neither a fascist nor an anti-Semite. Huge unemployment and increased social tensions brought anti-Semitism, but while Pilsudski was in power the police generally suppressed pogroms. After he died in 1935, conditions for Jews deteriorated considerably. There were boycotts of Jewish stores and street assaults, and a form of segregated seating known as “ghetto benches” was introduced at universities.

A major wave of pogroms included one in March 1936 at Przytyk, a small town in central Poland, whose population was 90 percent Jewish. When fascists attacked Jewish stalls, a Jewish self-defence group intervened. Two Jews and a Pole were killed, property was destroyed and more than 20 people were severely beaten.

This event inspired the Jewish folk poet and songwriter Mordecai Gebirtig to write “S’brennt” (It’s burning). Using flames as a metaphor for the threat of fascist violence, the song was intended as a call to action. Widely known in Poland before the war, it was later sung in many ghettos and camps and inspired young people to take up arms against the Nazis.

It’s burning, brothers, it’s burning!

Oy, our poor shtetl is burning,

Raging winds are fanning the wild flames

And furiously tearing,

Destroying and scattering everything.

All around, all is burning

The Jewish working class movement fought back using all the means it had. Although many groups and individuals participated, the main leadership was provided by the Jewish Labour Bund. Its goals were quite different to that of the Zionists: “Today as always our slogan is still true: right here [in Poland] and not elsewhere – in a relentless fight for freedom, arm in arm with the working masses of Poland – lies our salvation”.

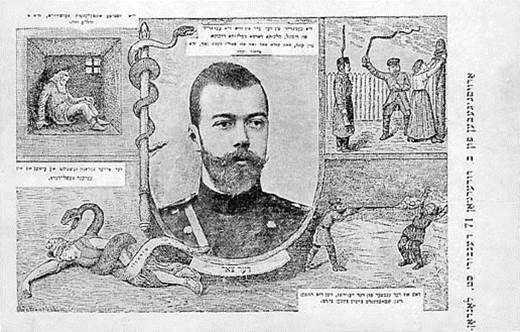

The Bund self-defence groups consisted of militias and 24-hour flying squads. Originally set up for the defence of the Bund, during the 1930s they broadened to the general defence of Jews: “their livelihood, dignity, honour and often their very lives”. One group was based on the Bund youth organisation Tsukunft (Future). The adult group (the Ordenergruppe) included Bundists and Jewish unionists and was allied with a PPS militia. A Bund leader declared their defiance at a 1937 rally:

“Today, the Jewish working class is saying to the fascist and anti-Semitic hoodlums: the time has passed when Jews could be subject to pogroms with impunity. There exist a mass of workers raised in the Bund tradition of struggle and self-defence … Pogroms [will not] remain unpunished.”

The squads broke up anti-Semitic pickets at Jewish stores, patrolled areas at risk and responded to fascist assaults in the universities. Sometimes, they arrived early in sufficient force to prevent an attack. At other times, they carried out organised retaliations. Perhaps the most important battle occurred in the Saxonian Garden, a Warsaw park, in 1938. Bernard Goldstein, a leader of one of the Bund self-defence groups, described what happened:

“We organised a large group of resistance fighters which we concentrated around the large square near the Iron Gate. Our plan was to entice the hooligans to that square, which was closed off on three sides, and to block the fourth exit, and thus have them in a trap where we could give battle and teach them an appropriate lesson … When we had a fair number of Nara [fascist] hooligans in the square … we suddenly emerged from our hiding places, surrounding them from all sides … ambulances had to be called.”

Important as self-defence groups were, only relatively small numbers of committed and trained individuals could participate. The other critical component of the fight back was street mobilisations. Throughout the late 1930s, there were numerous small demonstrations in the streets, many almost spontaneous. Frequently, these were broken up by police. There were also large, organised protests. In March 1936, a half-day general strike, originally called by the Bund to protest against the Przytyk pogrom, turned into a mass protest against anti-Semitic violence. The action was supported by the PPS, and some Polish workers – mostly socialists – joined in; much of Poland was shut down.

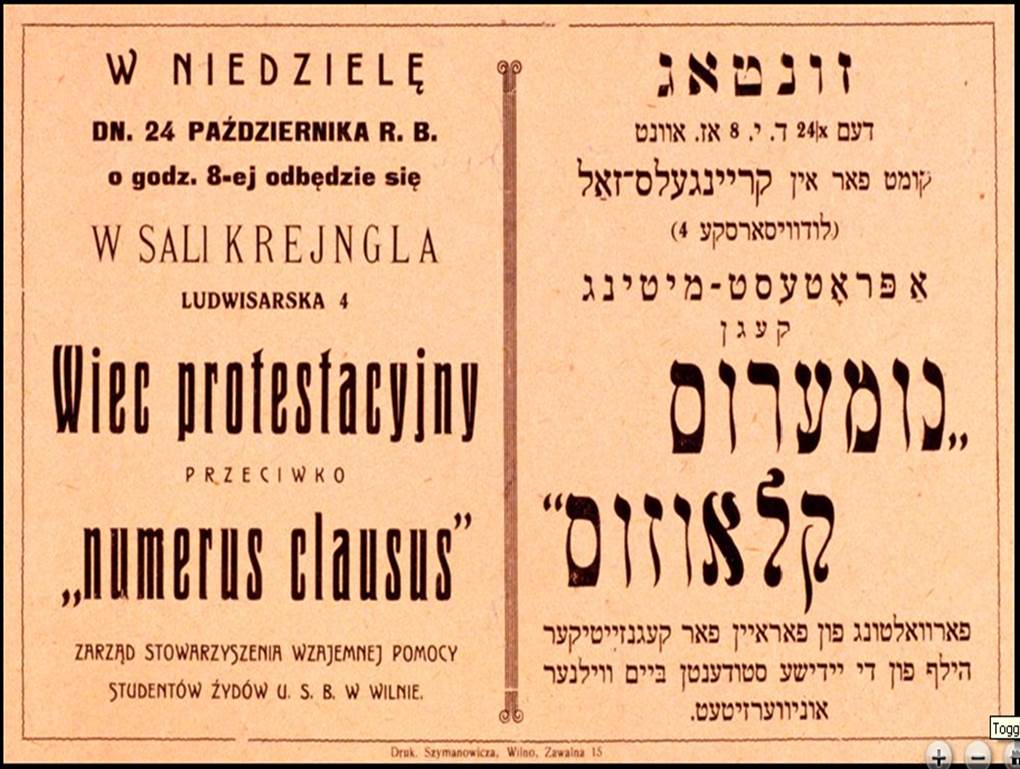

A year later, a demonstration against the government’s failure to punish those who had incited a pogrom at Breszcz resulted in a massive turnout. And in October 1937, a two-day general strike included a mass protest in Warsaw against the ghetto benches and the terror at universities. This drew in not just the Jewish community, but also PPS unions, academics and many others. The participants drove off fascist attacks. A Jewish high school student wrote: “The whole Jewish community chose to protest against this injustice … We know that after the university ghetto will come ghettos in other aspects of life … The streets were filled with [protesters]. Jewish stores were closed. The whole community showed its solidarity”.

The Bund could lead such impressive actions because it had a base in the working class, built up over decades. These militant workers were ready to respond to the call to action. They could mobilise the broader Jewish trade union movement and students. But alone, these strengths would not have been sufficient. Crucially, the Bund drew support from outside the Jewish community, in particular Polish socialists. Through them, they often received tip-offs about planned attacks, and their support at the demonstrations was invaluable.

It is a widespread myth that all Poles are inherently anti-Semitic, with deep hatred of Jews imbuing Polish society. Anti-Semitism in Poland in this period was in fact primarily a ruling and middle class phenomenon. The bulk of the Polish working class supported the PPS, which, as historian Lenni Brenner showed in Zionism in the Age of the Dictators, understood from the beginning that the fight against anti-Semitism and the fascists was its fight. The absence of anti-Semitism among the working class was acknowledged by Jacob Lestchinsky, a leading Zionist scholar:

“The Polish labour party may justly boast that it has successfully immunised the workers against the anti-Jewish virus, even in the poisoned atmosphere of Poland. Their stand on the subject has become almost traditional. Even in cities and districts that seem to have been thoroughly infected by the most revolting type of anti-Semitism the workers have not been contaminated.”

Facing the strong anti-Semitic currents at the universities was a layer of non-Jews who resisted. When segregated seating was first introduced at Lvov (present day L’viv, Ukraine) Polytechnic, Jewish students protested by standing rather than sitting in their places. They were joined in this action by some Polish students. When the ghetto benches were introduced throughout Poland in 1937, at least two university rectors resigned in protest, and more than 50 professors signed a petition against it. White Russian and Ukrainian students (also minorities in the Poland of the inter-war years) in Vilna and Lvov also joined the anti-ghetto actions.

Peasants were divided in their attitude to anti-Semitism; it was most common among the richer ones. The Peasant Party recognised by 1937 that the anti-Semitic campaign was a ruse to divert attention from political issues relevant to them. In return, Jews supported a mass 10-day general strike of peasants in August 1937 in which police killed 50 demonstrators. A Bundist youth leader reported: “During the strike you could see bearded Chassidim [religious Jews] on the picket lines together with peasants”.

Jewish confidence in the working class was demonstrated at the time of the Nazi invasion. According to the Labour Zionist Emmanuel Ringelblum, Jews tried desperately to find hiding places in the homes of workers: “Polish workers had long before the war grasped the class aspect of anti-Semitism, the power-tool of the native bourgeoisie, and during the war they redoubled their efforts to fight anti-Semitism ... There were only limited possibilities for workers to hide Jews in their home … [but] many Jews did find shelter in the flats of workers”.