There was never going to be a general call to resist. But in spite of the almost hopeless situation, Jews did fight back against the Nazis far more extensively than is currently recognised. They did not go as sheep to the slaughter. There were underground resistance movements in approximately 100 ghettos in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe (about a quarter of all ghettos) and uprisings occurred in five major ghettos and 45 smaller ones. In addition, there were uprisings in three extermination camps and 18 forced labour camps. Some 20-30,000 Jewish partisans fought in approximately 30 Jewish partisan groups and 21 mixed groups, and 10,000 people survived in family camps in the forest.

Ghetto underground organisations communicated with partisans and provided them with information or supplies, carried out non-military sabotage, helped POWs and escapees, distributed illegal information and money, forged documents and published newspapers and proclamations. Individuals and illegal groups helped Jews to find the necessities of life in the ghettos, to escape and to find arms.

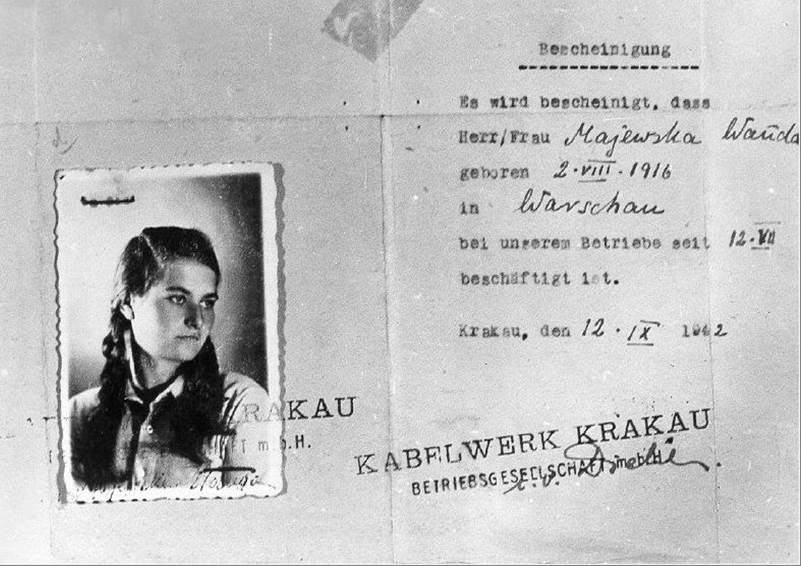

Thousands of couriers worked to overcome the isolation of the ghettos at great risk to themselves. Often they were women because they could pass as non-Jews more easily (Jewish men were all circumcised). Tema Schneiderman, a courier for the Jewish underground in Vilna (Lithuania), Warsaw and Bialystok (Poland), secretly delivered news and ammunition. Ania Rud, a former member of the Bialystok Ghetto underground, lived outside the ghetto as a White Russian and acted as a contact between couriers, the local underground and forest partisans. Marylka Rozycka, a member of the Communist Party in Lodz, was Jewish but looked like a Polish peasant. She maintained contacts between the Communist Party and the ghetto underground and later joined the partisans in the forest.

Major efforts went into collecting information and recording events. Krakow activist Gusta Draenger was arrested after a grenade attack on a Nazi coffee shop. She recorded the history of the Krakow underground on toilet paper while in prison. This document still exists. Bund member Zalmen Frydrych met escapees near Treblinka and obtained information about the death camps.

‘WE WILL NOT OFFER OUR HEADS TO THE BUTCHER LIKE SHEEP’

The underground in Bialystok began in late 1941 with the establishment of groups to help Soviet POWs, who received appalling treatment from the Nazis. The activists, the majority of whom were young, established contacts with Polish supporters and were able to smuggle in some weapons.

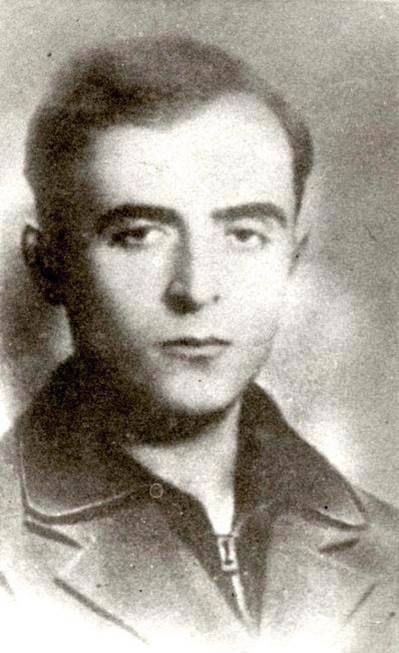

In late 1942, the Warsaw ZOB decided to organise armed resistance in the other key ghettos and sent Mordechai Tenenbaum (Josef Tamaroff) to Bialystok. Under his leadership all political factions, including the Communists, Bundists, Labour Zionists and other Zionists, united and prepared for an uprising.

The Bialystok Jewish Council, on the other hand, was dominated by older people. Although the Zionist chairman Efraim Barasz was aware of the mass murders and destruction of communities, he refused to cooperate with the underground, arguing that, because the ghetto was “productive”, the Germans would leave it alone. When the council handed over 6,000 Jews to the Nazis in February 1943, some underground groups put up armed resistance, including 20 young men led by Edek Borak. Others resisted with acid, axes, knives and boiling water. Afterwards, people searched for informers who had led Nazis to hideouts.

“When a cry of ‘traitor’ was heard, crowds rushed to the scene. They would tear and claw at the suspect, and lynch him on the spot”, noted Arnold Zable in Jewels and Ashes. On May Day 1943, there was a strike among the forced labourers in the factories. Protest demonstrations or absence from work were not possible. But the workers stood idle near their inactive machines, turning them on when they saw a German approaching and off the moment the German left.

The underground activists in most of the ghettos faced a terrible dilemma. An armed uprising could not hope to achieve anything if it was isolated; it would require the support of a significant section of ghetto inhabitants. But the ghettos were full of children, old people and other non-combatants, and arms were difficult to come by. The other option was escape, usually with an intention of joining the partisans. While this had a better chance of success for individuals or small groups, it meant leaving the rest of the population to its fate.

Top row: L-R: ?, Mordechai Tenenbaum, Shlomo Goldstein

Middle row L-R: Moske Nowoprucki, Dan Gelbart, Natan Blizowski, Rywka Cyrlin, ?

Seated L-R: Dawid Kozibrodcki, Avraham Gewelber, Yitzhak Perlis, ?, Feiwel Wigdorhaus

The situation in Bialystok illustrates the predicament. The underground met on the evening of 27 February 1943, believing the Germans planned to liquidate the ghetto the next day. Minutes of this meeting have survived. The leader, Mordecai Tenenbaum, commented: “It’s a good thing that at least the mood is good. Unfortunately, the meeting won’t be very cheerful … We must decide today what to do tomorrow”. He went on:

“We can do two things: decide that when the first Jew is taken away from Bialystok now, we start our counter-Aktion … It is not impossible that after we have completed our task someone may by chance still be alive … We can also decide to get out into the forest … We must decide for ourselves now. Our daddies will not take care of us. This is an orphanage.”

In fact, liquidation did not occur until later in the year. The planned attack and mass escape into the forest failed. The underground staged a heroic 10-day uprising from 16 August 1943, but, having failed to win the support of the ghetto population, it was isolated.

Vilna was an important Jewish cultural centre. The underground United Partisan Organisation (Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye, FPO) was formed on 1 January 1942 when Abba Kovner spoke at a clandestine public meeting held in a soup kitchen. Also known as “the Avengers”, they carried out many sabotage operations. In their first action, Vitka Kempner and two companions blew up a Nazi military transport carrying 200 soldiers on the outskirts of the town. Abba Kovner recorded:

“Lithuanians did not do it, nor Poles, nor Russians. A Jewish woman did it, a woman who, after she did this, had no base to return to. She had to walk three days and nights with wounded legs and feet. She had to go back to the ghetto. Were she to have been captured, the whole ghetto might have been held responsible.”

The action was memorialised in a famous song by Hirsh Glik, “Still the night was full of starlight”. Vitka became one of Kovner’s chief lieutenants and was later involved in many acts of resistance. She survived the war and died in February 2012. Eighteen months after Vitka’s operation, when the liquidation of the ghetto was imminent, the FPO issued a manifesto inspired by the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and called on the remaining Jews to resist deportation. It declared: “We will not offer our heads to the butcher like sheep. Jews defend yourselves with arms … Active resistance alone can save our lives and our honour”.

But the Jewish Council opposed the call and refused to cooperate, arguing that armed resistance would lead to destruction of the ghetto population. When the Nazis liquidated the ghetto, virtually all of its inhabitants went to their deaths in forced labour camps or the Sobibor death camp or were murdered individually. A few hundred members of the underground organisation, including Kovner, escaped to become partisans in the forest.

In Kovno (Kaunus, central Lithuania), a large underground of 600 members was led by Chaim Yelin, a Jewish Communist who united the Communists and Zionist youth groups. The Jewish Council supported the underground, as did a number of the ghetto’s Jewish police. Among the Poles who helped the Jewish underground in Kovno was Dr Kutorghene. She explained why she risked her life:

“You gave me courage, you gave a new lease of life, encouraged me. I feel I am stronger when I am with you and do not want you to go even though we both risk our lives and lives of our family members.”

Ultimately, there was no uprising. But 500 ghetto fighters escaped to join Jewish partisan groups. When the ghetto was liquidated, the population refused to present themselves for deportation following an appeal from the underground. Many people went into hiding for as long as possible, although the Nazis set the ghetto on fire.

Of the smaller ghettos, Lachva (Belarus) was in August 1942 one of the first to show resistance as a united community, possibly because the Jewish Council supported the underground. The uprising started during the liquidation of the ghetto. People had no guns, so they set fire to the ghetto and attacked the Nazis with axes, knives, iron bars, pitchforks and clubs. An account based on the recollections of one participant, Yitzhak Lichtenstein, notes:

“The fire and smoke, along with the spontaneous Jewish attack, created panic among the Germans. The Jews took the opportunity to break through the ghetto fences. Under heavy fire, hundreds of Jews ran towards the swamps in the forest. 600 people escaped … including elderly people, women and children.”

Approximately 150 people made it to the swamps and later joined the partisans.

Barbara Epstein, in The Minsk Ghetto 1941-1943, showed that Minsk was the location of one of the most successful of the underground organisations. The city, in present day Belarus, had been part of the Soviet Union before the war. Their experience during the war was perhaps unique in that Jews and non-Jews were united in one Communist-led underground organisation across the ghetto and the main city. Epstein emphasises the “culture of solidarity between Jews and non-Jews” within the underground organisation but also points to personal support and interaction outside the formal underground organisation.

Formed in late 1941, the underground ran a clandestine press and smuggled Jewish children out of the ghetto to hide them in other parts of the city. Jews and non-Jews both engaged in sabotage within Nazi factories. For instance, shoemakers put nails into shoes to make them unwearable, and tailors sewed left arms into right armholes of coats and vice versa.

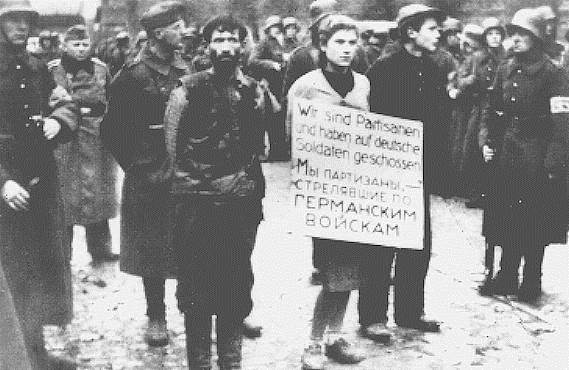

Participation in the underground was very dangerous. One well known example is the case of Masha Bruskina, a 17-year-old Jewish member of a Communist underground group located outside the ghetto, who helped wounded Soviet POWs. Captured in October 1941, she was hanged with two other non-Jewish members of the underground, Krill Trus and Volodya Sherbateyvich, in the first public execution of resisters.

Rather than armed uprising, the Minsk underground focused on flight, which their circumstances particularly favoured. A barbed wire fence (rather than the high wall found in other ghettos) and relatively lenient guards made access to the nearby dense and impenetrable forest dangerous but possible. A major factor was also the support from the first two Jewish Councils, which were more closely intertwined with the underground than elsewhere. The courageous stand of council members no doubt contributed significantly to the high number of escapes, but they paid a high price once exposed.

Led by child guides and helped by non-Jewish contacts, roughly 10,000 Jews escaped from Minsk; most of them survived the war. This was the most successful ghetto resistance in terms of numbers saved and deserves to be as widely recognised as the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

The Minsk underground supported and sent supplies to the partisans and also carried out successful sabotage within the town. A letter in a German newspaper in June 1943 described the situation:

“Partisans are everywhere, even in the city of Minsk. In the last months many Germans have been killed in the streets. You can’t travel along the Vilna-Minsk highway. You can move in the direction of Baranovichi only escorted by tanks … a mine was planted in the city theatre … as a result more than 30 people were killed and about 100 were wounded. Then they blew up an electric power station and the steam tank at the dairy plant.”

Front row L-R: B. Chaimowicz, S. Zorin, H. Smoliar

Back row L-R: C. Feigelman, Y. Kraczynsky, N. Feldman.

The story of the fate of the surviving underground members after the war is a sorry one. Not only were they not treated as heroes by the Soviet regime; they were arrested, and many spent years in prison or keeping their heads down. This was partly due to an assumption by the Soviets that anyone who came under Nazi rule and survived must have been a collaborator. The whole process was exacerbated by a local Communist who invented an account of a massive evacuation from Minsk to conceal the fact that he and his friends had fled. Those arrested were not exonerated until 1962.

‘TODAY PARTISANS ARE GOING TO BEAT THE ENEMY’

Partisan units were a feature of the northern forest area. The groups were disparate, but Soviet POWs who had escaped from the horrendous Nazi POW camps figured large. In the early days, the units tended to be anarchic, loose and disorganised; life was extremely difficult and conditions, in Tec’s word, were “inhuman”. So the partisan movement should not be romanticised; forest conditions where dirt, hunger, exhaustion, danger and fear were the daily experience naturally bred suspicion, hierarchy, internal conflict – and anti-Semitism. Tec writes that “few forest dwellers resembled the idealised image of the fearless, heroic fighter” and that “In these jungle-like forests, a jungle-like culture emerged”.

Many partisans in Belarus were Communists. Later, the units became more organised as Stalin implemented a program of control over them with an eye on postwar Poland.

In 1944, at least 159 Jewish partisans were active in the Parczew forest north of Lublin (Poland). They cooperated with the Soviet partisans in a number of engagements against the Nazis, including the takeover of the city of Parczew in April 1994. However, not all the partisans were Soviet controlled. When the Avengers from Vilna moved into the forest after the liquidation of the town, they destroyed the town power plant and the waterworks. In honour of International Women’s Day, Gertie Boyarski and a friend – both in their teens – demolished a wooden narrowbridge used by the Nazis.

The dilemma of the ghettos also applied in the partisan setting. What were the many people who fled the ghettos but unarmed and unable to be fighters to do? The partisan groups often would accept only young men with arms, whereas fleeing Jews often arrived without weapons or skills; an estimated 80 percent died. About 10,000 Jews did survive in family camps, which provided shelter and support for non-fighting people as well as armed partisans. The most famous, Bielski Otriad, focused on rescuing Jews and accepted anyone of any sex or age who could reach them. Another non-military group was, astonishingly, a musical troupe based near the village of Sloboda in Belarus. The group of 25 included three Jews – Chana Pozner, her father Mordechai Pozner and Yehiel Borgin – and provided entertainment for the partisan units.

‘THE CREMATORIUM WAS BURNING AGAINST A DARK SKY’

The name Auschwitz is virtually synonymous with death camp. It was in fact much more than that. Auschwitz-Birkenau, situated near the town of Oswiecim in south-west Poland, consisted of three main sections, including transit camps, labour camps, extermination ovens and 45 satellite camps.

Resistance occurred in many areas at Auschwitz. The Union Factory (Weichsel-Union-Metallwerke), which was owned by Krupp, employed forced labourers who manufactured a range of explosives and armaments. Krupp had complete control over the production, while punishment was “inflicted by the SS at Krupp’s request”. Workers, many of whom were Jews, carried out sabotage and participated in the uprising.

The underground organisation at Auschwitz included Polish political prisoners, forced labourers and Jews from the Sonderkommando (special unit) – the group responsible for dealing with the remains from the crematorium. The Auschwitz underground published a newspaper and even transmitted by radio direct to London. Witold Pilecki, a member of the underground Polish Home Army, voluntarily smuggled himself into Auschwitz in 1940 and set up an organisation whose main purpose was to send information out of the camp. He escaped in 1943, after realising that the Allies did not intend to liberate those interned.

The underground organisation planned a revolt and prepared weapons using gunpowder smuggled out of the Union Factory by women forced labourers such as Rosa Robota. Having heard that the Sonderkommando was about to be liquidated, on 7 October 1944, camp inmates attacked the guards with axes and knives; the SS responded with machine guns. The Sonderkommando members then blew up one of the crematoriums with grenades made from smuggled dynamite. Tec notes:

“In no time the entire guard force of the camp was mobilised against the rebels. Bullets were flying all over the place. SS with dogs were chasing the … rebels, many of whom fell while trying to escape … When they realised that they had no chance of survival, they set the forest on fire … As the day was coming to an end Auschwitz was surrounded by guards and fires. The crematorium was burning against a dark sky, as were small forests on opposite sides of the camp. The ground was covered with dead bodies of the members of the Sonderkommando.”

A total of 250 prisoners died during the uprising, and 200 were later shot. None escaped. Perhaps two or three Nazis died and a dozen were wounded. Rosa Robota and three other women were hanged in Auschwitz the following January, only three weeks before the camp was liberated by the Soviets. After the war the Krupp-owned Union Factory received 2.5 million marks as reparation for the factory it lost at Auschwitz. The forced labourers received nothing. The Allies agreed to postpone, and the German Supreme Court barred, claims from forced labourers. Finally, in 1993, 22 survivors sued the former factory, with back pay being awarded in 1997 to only one of them. The court determined that the others were sufficiently compensated by governmental reparations.

The uprising in Sobibor concentration camp in eastern Poland was more successful. The underground leadership consisted of a Jew, Leon Feldhandler, and a Soviet POW, Sasha Pechersky. Having learned about the Warsaw Ghetto uprising from deportees from that city, they made their own plans. On 14 October 1943, the group lured SS officers into the storehouses and attacked them with axes and knives, killing 11, including the camp commander. The rebels then seized weapons and ammunition and set fire to the camp. Tomasz (Toivi) Blatt described what followed:

“During the revolt prisoners streamed to one of the holes cut in the barbed-wire fence. They weren’t about to wait in line; there were machine guns shooting at us. They climbed on the fence and just as I was half way through, it collapsed, trapping me underneath. This saved me … [as the] first ones through hit mines. When most were through, I slid out of my coat, which was hooked on the fence, and ran till I reached the forest.”

Ultimately, 300 of the total of 600 prisoners escaped. Nearly 200 avoided recapture; some were hidden from the Nazis by Poles.

The underground at Treblinka (north-east Poland) was organised by a former Jewish captain of the Polish Army, Julian Chorążycki. After months of preparations, on 2 August 1943, they stole arms from a warehouse, killed the guards, set the camp on fire and destroyed the extermination area. They then helped prisoners to escape into the forest. All resistance leaders were killed as the Germans retaliated. Out of 1,500 prisoners in the camp, approximately 600 escaped, the majority of whom were recaptured. Some of the escapees were helped by the Polish Home Army or by Polish villagers.

Despite the losses, these two uprisings resulted in the closure of the camps, which must be regarded as an achievement.