The establishment of the ghettos was the first step in the Nazi plan to annihilate the Jews. Descriptions of life in these hundreds of walled, isolated and tightly controlled communities defy the imagination. For example, in Minsk, a living space of 1.5 square metres was allotted per adult; no space at all was allotted for children. The food ration was 400 calories a day – about two potatoes. In Warsaw, people returning home with their tiny bread ration had to ignore children dying in the street.

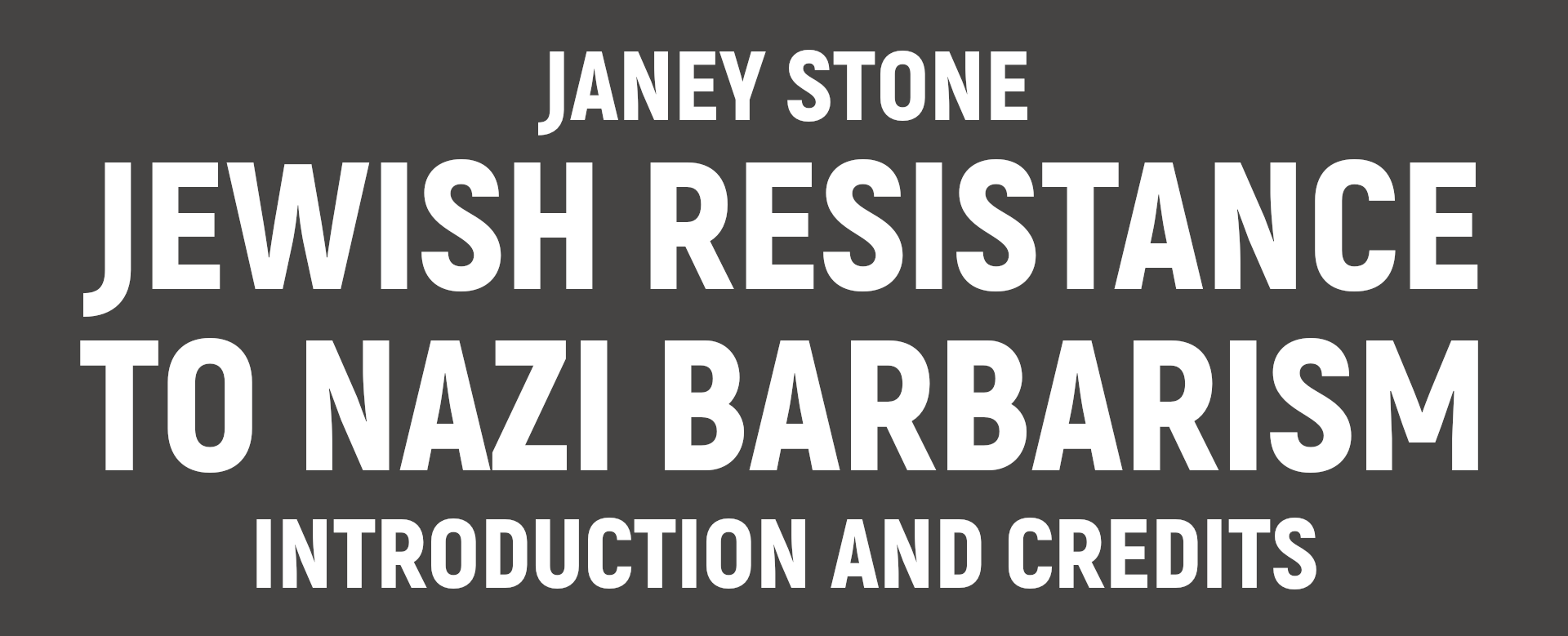

Re: death penalty for illegally leaving the Jewish residential district

Recently, in many documented instances, Jews, who have left the residential districts designated for them, have spread typhus. To safeguard the population against this dangerous threat, the General Governor has ordered that any Jew, who in the future illegally leaves the residential district designated for him, will be punished by death.

The same punishment will apply to whoever consciously shelters Jews mentioned above or in any other way assists them (for instance, by providing overnight accommodation, or sustenance, by giving a ride in any kind of vehicle, etc.)

The sentence is imposed by the Special Court in Warsaw. I explicitly draw the attention of the whole population of the Warsaw District to this new regulation since henceforth it will be applied with merciless severity.

Warsaw, 10 November 1941

Dr Fischer Governor”

Jan Karski commented after a secret visit to the Warsaw Ghetto, “[E]verything there seemed polluted by death, the stench of rotting corpses, filth and decay”. Marek Edelman, a leader of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, described the terrible atmosphere in his book, The Ghetto Fights:

“The Jews, beaten, stepped upon, slaughtered without the slightest cause – lived in constant fear. There was only one punishment for failure to obey regulations – death – while careful obedience … did not protect against a thousand and one fantastic degradations … [The] conviction that one was never treated as an individual human being caused a lack of self-confidence and stunted the desire to work … To overcome our own terrifying apathy, to fight against our own acceptance of the generally prevailing feeling of panic, even small tasks … required truly gigantic efforts on our part.”

The atmosphere was extremely corrupting. To obtain even the basic necessities of life, the population had to bribe, steal or lie. With shortages of everything and survival at the centre of everyone’s mind, some used their positions for personal advantage, such as to avoid forced labour. The Jewish police were notorious for supporting the Nazis in their actions. One ghetto inhabitant commented that they were “already known for their terrible corruption but reached the apogee of depravity at the time of the deportation”. There are horrifying examples of Jews spying for the Gestapo. But this was true not only of the Jewish population. It was divided like all others.

Concentrating the Jews in ghettos served the Nazis strategically, but there was also an ideological function. To commit atrocities, it is necessary to first dehumanise the victims; the ghetto environment facilitated this process. After a visit to the Warsaw Ghetto, the Nazi governor of Krakow commented: “A German would not be able to live under such conditions”, because they were a civilised people with a high culture and the state of the children of the ghetto was due to Jews being a diseased race. As Chaim Kaplan put it in his secret diary written at the time: “We are segregated and separated from the world…driven out of the society of the human race”.

In all ghettos, the Nazis created a special body, the Jewish Council (Judenrat), to act as an intermediary. The members were selected by the Nazis, and naturally they chose people who would cooperate. The members of the councils often saw their function as primarily welfare, running soup kitchens and so on. But to the Nazis, these activities were irrelevant. The Nazis used them to control the population, to provide labour power for the slave labour factories and, finally and chillingly, to process deportations to death camps. More Zionists were chosen for this role than all other political groups combined. The remainder were mostly the traditional conservative community leadership – rabbis and elders.

Jewish leaders who served in the councils clearly did not cause the Holocaust; the brutality of the Nazis was beyond the control of anyone subject to it. But the one thing that Jews could take responsibility for was their own response. Would they submit or would they resist? The responses of the council members varied greatly. Many argued that compliance would limit the damage or that, by making themselves economically useful, at least some Jews would survive. They argued that resistance could not be successful so it was futile.

This is a much disputed field. Yehuda Bauer discusses the research of Aharon Weiss into the behaviour of the Jewish Councils. Weiss drew a “red line” – active collaboration “meant handing over Jews to the Germans at the latter’s request”. An extreme example of this occurred in the Lodz Ghetto, where the head of the council, Mordechai Rumkowski, in Bauer’s words, was “without any doubt a brutal dictator”, who handed children over to the Nazis and turned the ghetto into a slave labour camp. An example of a different kind is the case of political collaboration known as the Kastner affair.

Lenni Brenner describes how, when the Nazis invaded Hungary in March 1944, Jewish leaders already knew about the exterminations from Polish and Slovakian Jewish refugees. But Rudolph Kastner, a Labour Zionist leader, did a deal with Eichmann, whereby he kept silent in return for safe conduct to Switzerland for 1,700 Zionist functionaries and their families. Eichmann later said: “We negotiated entirely as equals … We were political opponents trying to arrive at a settlement and we trusted each other perfectly”. Eichmann’s motive was concern about potential Jewish resistance or escape attempts to Romania, which by then was unwilling to hand Jews over to the Nazis.

Kastner’s collaboration helped the Nazis to murder 450,000 Hungarian Jews not long before the end of the war. Much has been written about this despicable act. An Israeli court ruled in 1958 that it was not collaboration, and the judge stated that Kastner’s actions were justified. The Israeli attorney general stated: “It has always been our Zionist tradition to select the few out of many in arranging the immigration to Palestine”. Kastner himself said: “The Hungarian Jew was a branch which long ago dried up on the tree”. Labour Zionists have never regarded him as a traitor.

Active collaboration is one thing. But the Jewish Councils that were not active collaborators but failed to support the underground groups and opposed active resistance to the Nazis, as was the case in several large and important ghettos such as Vilna, Bialystok and Warsaw, contributed to the outcome in a different way. Their attitude affected the populations in the ghettos; it exacerbated the feeling of hopelessness and made the building of resistance organisations even more difficult.

Feelings of hopelessness are understandable. Militarily, the situation was hopeless. Holocaust scholar Nehama Tec argues that there are five conditions upon which the possibility of successful armed resistance is predicated: time to prepare, a strategic base of operations, leadership, arms and allies. Overwhelmingly, these conditions were lacking. As Polish historian Lucjan Dobroszycki asked: “Has anyone seen an army without arms; an army scattered over 200 isolated ghettos; an army of infants, old people, the sick; an army whose soldiers are denied the right even to surrender?”

Yet there was resistance – and on a scale that has somehow disappeared from historical awareness. Jewish resistance occurred right across Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe. Definitions of resistance tend to divide into two groups. The first focuses on an active ideological component. “[Resistance] could develop only from an active ideology which presented its holders in opposition to the existing circumstances and believed in the possibility of changing the cultural and political ecology”, writes Eli Tzur. “Therefore the resisters usually had a previous history as members of anti-establishment groups.”

This type of definition applies readily enough to members of formally structured resistance organisations. The political parties, and above all their youth groups, formed the core of the underground. Overwhelmingly, it was young people who were able to recognise the true intentions of the Nazis and to organise against them, particularly Labour Zionists, the socialist Zionists Hashomer Hazair, the Bund youth group Tsukunft and Communist youth groups.

However, the Jewish population as a whole faced a situation in which almost all normal activities were banned by an enemy determined to exterminate them. In such circumstances, staying alive is defiance, and even efforts to hide or flee must be regarded as opposition. In this broader context, the definition offered by Nehama Tec sits better: “Activities motivated by the desire to thwart, limit, undermine, or end the exercise of oppression over the oppressed”.

Consider an incident in the small, eastern Polish town of Biala Podlaska, where my mother grew up. Some Jews who gave bread to Soviet prisoners of war marching through the town under guard in June 1941 were sent to Auschwitz and were among the first Jewish victims to perish there. Ideology does not enter into such acts of courageous defiant humanity, which occurred in everyday activities. Even simple survival activities such as soup kitchens required a defiant attitude. As one Vilna Ghetto inmate said: “[T]he resistance of the anonymous masses must be affirmed in terms of how they held on to their humanity, of their manifestation of solidarity, of mutual help and self-sacrifice”.

Such non-military Jewish opposition activities are often labelled “spiritual resistance”. But all resistance by Jews to the Nazis was political, whether armed or not and whether ideologically based or not. Defiance can be seen in the extraordinary range of cultural activities that occurred, including music, theatre and art. In addition, as an Australian survivor commented, “people kept their sense of humour, albeit grotesque, amidst the most appalling and unspeakable atrocities. We were always singing and telling vulgar jokes about our predicament”. A song in one concentration camp sung every evening contained the lyrics: “It’s already nine o’clock / All the camp is going to sleep / The latrines are locked up now / You’re no longer allowed to shit”.

RISING UP AGAINST THEIR DESTROYERS

The most famous example of resistance by Jews is the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

Nearly 400,000 people were sealed into the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940. The Jewish Council and much of the population tended to rationalise what was happening. But some of the Zionist youth groups recognised the Nazis’ intentions as early as March 1942 and called for the creation of a self-defence organisation, without success. The Nazis started mass deportations to Treblinka in July 1942, in the so-called Gross-Aktion Warschau. By then, more than 100,000 had already died due to starvation, disease or random killings. With another 250,000 to 300,000 people transported, the political groups finally faced up to the need for a united armed response.

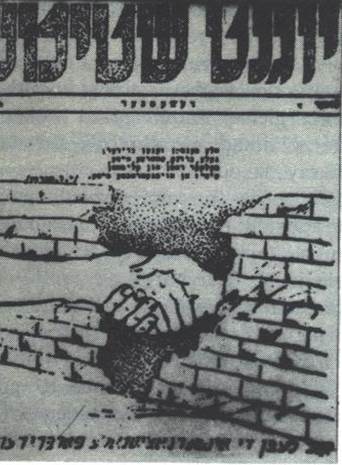

At the end of October 1942, three political groups – the Bund, the Labour Zionists and the Communists – formed the Jewish Fighting Organisation (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ZOB) under the command of Labour Zionist Mordechai Anielewicz.

When a second wave of deportations began on 18 January 1943, ZOB members fought back. The subsequent four days saw the first street fighting in occupied Poland. Despite their almost complete lack of arms and resources, the ghetto fighters were able to force the Nazis to retreat and to limit the number of deportations. Edelman, a member of the Bund and the five-person command group of the ZOB, wrote:

“For the first time German plans were frustrated. For the first time the halo of omnipotence and invincibility was torn from the Germans’ heads. For the first time the Jew in the street realised that it was possible to do something against the Germans’ will and power … [It was] a psychological turning point.”

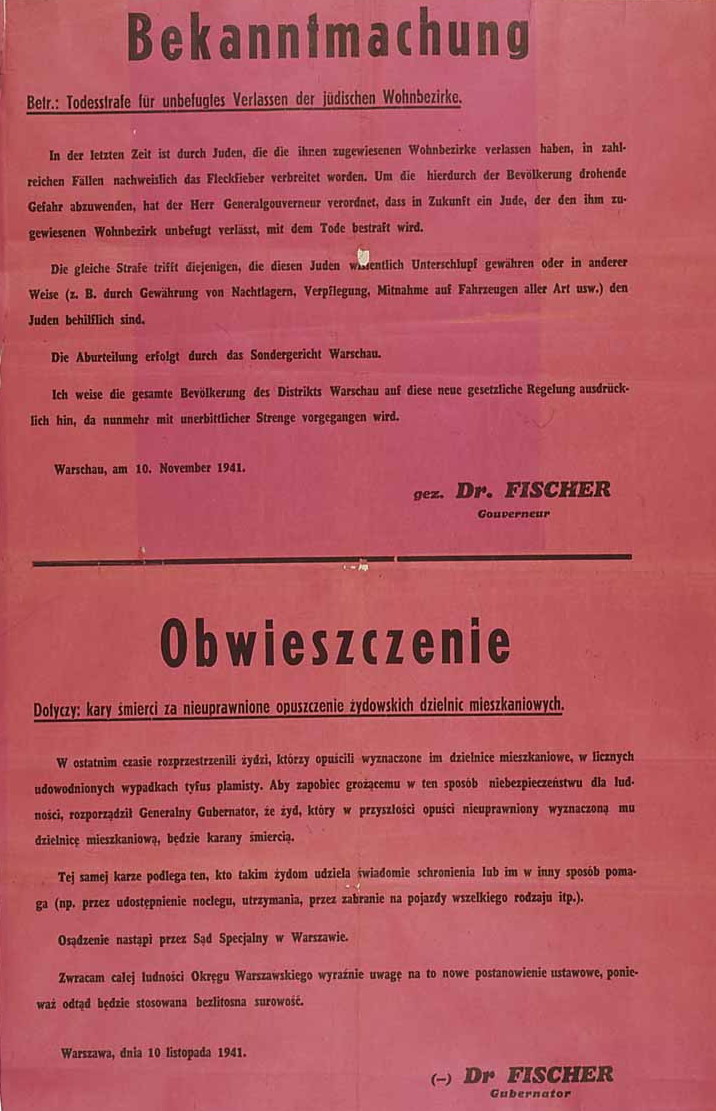

The ZOB then took control of the ghetto. With a very different approach to the typical Jewish Council, they executed Jewish police, Nazi agents and spies and prepared for military resistance. They oversaw all aspects of ghetto life, including the publication of newspapers and taxing wealthy residents.

Ghetto Yugnt Shtimme = Youth Voice.

“All people are equal brothers;

Brown, White, Black, and Yellow.

To separate peoples, colors, races

Is but an act of cheating!"

On 19 April, the German forces tried to resume deportations with a view to finally liquidating the ghetto. At this point, the ZOB had 220 fighters armed with some handguns (many barely functional), grenades and Molotov cocktails, a few rifles, two land mines and a submachine gun. Also part of the uprising, but not operating under the direction of the ZOB, was the Jewish Military Union (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, ZZW) with approximately 500 fighters consisting of former Jewish officers of the Polish army plus revisionist Zionists. The ZZW had somewhat better weapons due to links with the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK).

The German side consisted of more than 2,000 soldiers with heavy weapons including artillery, mine throwers and machine guns. With overwhelming military superiority, they anticipated an action of only three days. But the Nazi commander, general Stroop, was forced to report after a week: “The resistance put up by the Jews and bandits could be broken only by relentlessly using all our force and energy by day and night”.

The uprising lasted six weeks and necessitated fighting from building to building and ultimately setting fire to the ghetto. As Edelman wrote, the insurgents “were beaten by the flames, not the Germans”. Organised resistance was over by the end of April, but localised resistance continued until June. Many people hid in bunkers and were forced out only by smoke bombs.

The stories of personal bravery are inspiring and heartbreaking. Edelman described a young boy, Dawid Hochberg, blocking a narrow passageway. After he was killed, his wedged body took the Germans some time to remove, allowing the escape of fighters and civilians. A number of captured fighters – especially the women – threw hidden grenades or fired concealed handguns after surrendering, killing themselves with their captors. Some Polish resistance members fought with the Jews inside the ghetto. Polish resistance groups also engaged the Nazis at six different locations outside the ghetto walls to help divert the German forces.

“What took place exceeded all expectations. In our opposition to the Germans we did more than our strength allowed”, Anielewicz noted in his last letter. Even Goebbels (unintentionally) paid the resistance tribute: “The Jews have actually succeeded in making a defensive position of the ghetto … It shows what is to be expected of Jews when they are in possession of arms. Unfortunately some of their weapons were good German ones”. The ghetto uprising was a military failure. But as Yitzhak Zuckerman, second in command of the ZOB, said, there is no need to analyse it in military terms, “The really important things were … in the force shown by Jewish youths … to rise up against their destroyers and determine what death they would choose: Treblinka or Uprising”.

The uprising had an enormous impact on the Polish population as well as the Jews, and intensified resistance throughout the country. Many of the other uprisings were directly or indirectly inspired by the ghetto insurgents.

‘WE SHOULD HAVE RAISED THEM IN THE SPIRIT OF REVENGE’

When the Nazis set up the Warsaw Jewish Council in August 1939, it was argued that at least one Bund member should participate. Shmuel Zygelboym reluctantly joined. However, the demands of the position soon came into conflict with his politics. When the Nazis attempted to set up the ghetto in October, Zygelboym refused to help. Instead he addressed Jews gathered outside the organisation’s headquarters, and told them not to cooperate but to remain in their houses and make the Nazis take them by force. This single call for resistance succeeded in having the order to establish the ghetto cancelled for several months.

The leader of the Warsaw Jewish Council, Adam Czerniaków (a general Zionist), behaved differently. He carried out Nazi instructions, including providing lists of people to be deported, even though he knew their fate. In this he was supported by the Jewish police. Edelman commented about a council meeting in July 1942 in response to the German demand that all “non-productive” Jews be deported in the Gross-Aktion Warschau:

“Not a single councilman stopped to consider the basic question – whether the Jewish Council should undertake to carry out the order at all … There was no debate on the implications of the order, only on the … procedure for its execution … Thus the Germans made the Jewish Council itself condemn over 300,000 ghetto inhabitants to death.”

The role of the youth in the creation of a fighting organisation was central. Immediately following the Nazi invasion of Poland, most of the top leaders of the Zionist organisations went into exile, leaving secondary leaders and the youth groups to lead the response. Similarly, the Bund leadership largely departed, leaving the youth group Tsukunft to play a leading role in the party’s underground activities.

Unfortunately, the remaining Bund leaders were reluctant to unite in an underground organisation with the Zionists. They rejected the call for unity in March 1942, at which time Abrasha Blum from the youth group was in favour of a joint fighting organisation, but felt he had to defer to his senior, Maurici Auzach, who was against. The Bund finally joined the ZOB in October. For virtually their entire history they had (rightly) opposed Zionism. But the situation faced by the population of the ghetto was beyond normal political conflicts. The Nazis planned to annihilate Jews of all political currents, and military action required unity with anyone who was prepared to take up arms. It took the efforts of the youth group, in particular Blum, to convince the adults of the Bund to join a united fighting organisation.

The Zionists in the ghetto were hamstrung by their politics in a different way. In the first period, even the youth groups mainly engaged in communal activities. Emanuel Ringelblum, who created an archive detailing life in the ghetto, described how Anielewicz regretted the delays and failure to face up to the necessity of armed resistance and felt that they “had wasted three war years on cultural and educational work”:

“We had not understood that new side of Hitler that is emerging, Mordechai lamented. We should have trained the youth in the use of live and cold ammunition. We should have raised them in the spirit of revenge against the greatest enemy of the Jews, of all mankind, and of all times.”

Yitzhak Zuckerman, a founder of the ZOB and later a historian of the Warsaw uprising, stated baldly: “The Jewish Fighting Organisation arose without the parties and against the wish of the parties”.