I certainly didn’t expect to spend the start of 2020 wading through nearly 700 pages about the 1892 Hamburg cholera epidemic, but I’m glad I did. Death in Hamburg, British historian Richard J. Evans’ social history of the epidemic, is a page-turner, his passion for the topic nothing short of infectious.

At the time it was published in 1987, the contemporary parallel was the spread of HIV-AIDS. The parallels with our sorry times are, if anything, more direct. It’s a tale of official indifference, denial, opportunism by the wealthy and callousness towards the masses.

It is also the story of how a disease brought about a profound political and economic upheaval, such that up until WWI, the history of the city was measured “before” and “after” the epidemic. Upended particularly was the relationship between social classes – the old rulers being discredited and those previously sidelined decisively entering the stage. The epidemic, in other words, changed everything.

********

Cholera is caused by bacteria that grow on marine animals which, when they get into the water supply and are consumed by humans, cause violent diarrhoea, which can lead to death in as little as 24 hours. It is a horrible fate, like “a thousand devils ... pulling at one’s innards or perhaps sawing one’s body in half at the same time”, as Evans elsewhere describes it.

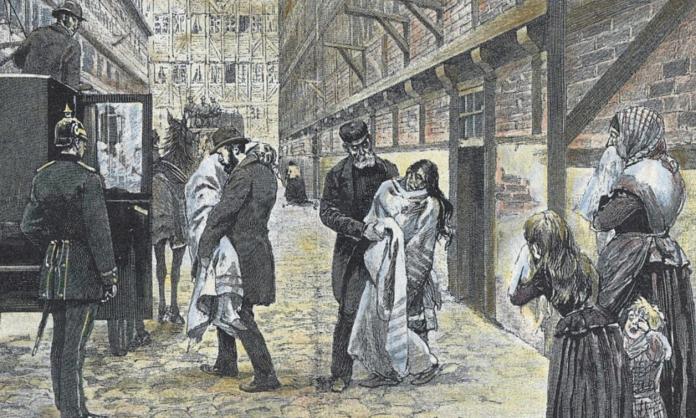

The disease killed 10,000 of Hamburg’s 800,000 inhabitants in just over six weeks during August and September 1892. Around half of those affected died, many before they could receive medical attention.

Several factors led to the bacteria entering the city’s water supply. One was their arrival on a migrant train from Russia, and the unsanitary disposal of waste from overcrowded migrant accommodation. Another was the drought of 1892, which enabled the bacteria to travel further upstream in the river Elbe (from which Hamburg’s water supply was sourced) than they would have otherwise. But the most important was the most scandalous: neglect on the part of the city’s authorities to construct a water purification system in advance of the epidemic.

Following a 1873 cholera outbreak, the Hamburg Medical Board pressed for a filtration system for the city’s water supply. Eight years later, the Citizens’ Assembly agreed in principle, but fears about possible incursions on the interests of the wealthy, especially within the Property Owners Association, which was well represented in the Citizens’ Assembly, derailed the project.

Ultimately, priority was given to projects that furthered the city’s prestige rather than helped its residents, such as, “the building of the new Town Hall , a grandiose ‘Renaissance’ edifice designed ... to provide a symbolic reaffirmation of the waning power of the City Fathers”.

This reflected the politics of the city: economics ruled. The largest European seaport and the fourth richest in the world at the time, Hamburg was controlled “by an oligarchy of wealthy merchants, who dominated the city’s administration and appointed all its senior officials including medical and public health officers”. It was a bastion of laissez-faire liberalism, where trade was paramount.

This largely explained the authorities’ disastrous response. When the first cholera-like cases were noted, the official reaction was denial. When the outbreak could no longer be denied, they dragged their feet implementing measures to stop contagion, prioritising their commercial interests over lives.

Robert Koch, a prominent microbiologist and advocate of the (now accepted) contagionist theory of disease, was sent to Hamburg by the German central government to take control of the outbreak. But he first had to wage a political battle against the Hamburg establishment, which favoured the prevailing “miasma” theory. This posited that disease was the product of a cloud-like miasma that rose up from the ground, particularly where conditions were dirty, an explanation preferred in Hamburg, not for its scientific merit, but because it meant blame could be laid at the feet of lazy, unclean and irresponsible poor people rather than the city authorities.

Koch insisted on a variety of measures – including the imposition of quarantine, disinfection and cleaning of public places and homes, the distribution of free, uncontaminated water and a public information campaign about how to stop the spread – which Hamburg’s officials only begrudgingly agreed to implement.

Even then, health was far from their first priority. Mass dissemination of disease control information, for example, was not implemented until a whole week after it was agreed to. In addition to being deadly, this delay was political. Not possessing the popular support needed to carry out the task itself, the Senate was forced to swallow its pride and call on the only force that did: the local branch of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

But days were allowed to pass before the party was contacted, as Evans argues “likely so that the distribution would take place on the next available Sunday (28 August) and so avoid any disruption of work, with its consequent loss of profit to the employers. Had the distribution taken place on the 26th or 27th, thousands of Social Democratic party workers – overwhelmingly manual labourers – would have had to take time off work” and because at the request of the authorities, their bosses wouldn’t have been able to penalise them for it. This would have saved lives, but at the cost of all-important profits.

The same logic applied in the treatment of the many migrants in Hamburg, at the time an entry point for western Europe; thousands were temporarily housed in the city. Concerned not to be held financially responsible for them in the event of quarantine measures being imposed, the city’s authorities rushed to give clean bills of health to the migrant ships waiting to leave, despite being aware that cholera had infected the city. This not only killed many passengers, it also spread the infection to other parts of Europe and the US.

As the traditional rulers of Hamburg were increasingly discredited through repeated episodes like this, the previously shunned and ostracised Social Democrats were able to gain a greater following. The Hamburg branch of the party was conservative even by the reformist Social Democratic Party’s standards, but it was nevertheless able to connect with the popular anger created by the epidemic.

On 4 November, the party held nine simultaneous mass meetings, which attracted a combined attendance of 30,000 according to the bourgeois press at the time. All “had a common theme”, wrote Evans, “that the epidemic had been caused by the incompetence and greed of the Hamburg Senate”. Speakers agitated for greater health care, public sanitation and an extension of suffrage to undermine the power of the merchants.

The Social Democrats were pushing on an open door – the poor were affected by cholera more acutely than the wealthy. In part this was because of the crowded and filthy conditions workers and the poor were compelled to live in. But, more importantly, wealth provided protection from the disease. The wealthy had the ability to read and therefore take note of public notices, the means to flee the city and access to servants with time to boil water and sanitise their houses for them. For Hamburg’s poor, most of the necessary sanitary measures were simply not practical, even if they were made aware of them.

Workers and the poor were also the most hard hit by the economic effects of the epidemic, especially unemployment. Thousands were suddenly without work, and remained so months later. In January 1893, 18,000 workers were registered as looking for work on the docks; fewer than 5,000 were successful. In the same month, 70 workers occupied the city engineer’s department demanding jobs, and the mounted police were called to quell a riot outside a labour exchange.

While on the one hand dismissing the unemployment problem as Social Democratic “bluster”, the wealthy also self-servingly invoked it as a reason to roll back health measures and get the economy back to normal. Supposed concern on the part of the Chamber of Commerce for the “very many groups” affected by “redundancies and dismissals” featured prominently in its campaign to remove quarantine regulations and restore manufacturing and trade.

In the epidemic’s aftermath, the level of popular anger meant the ruling class had no choice but to offer reforms of various sorts, particularly in housing, planning and public sanitation. A further motivation was concern that the city might be taken over by the German central government and lose its self-governing status, so calamitous was the perception (and reality) of the Hamburg authorities’ mishandling of the epidemic.

But as 1892 gradually receded into history and the threat of absorption into greater Germany subsided, these reform efforts quickly petered out. Unfortunately, the Social Democrats – the only force in Hamburg that could have forced the authorities’ hand and successfully pushed for real gains for workers – were unwilling to lead the necessary social rebellion.

Their organising efforts later in the epidemic, honourable though they were, were largely in response to the radicalism of the bourgeois press in the face of official incompetence. Left to its own devices, the party had tended more to embrace the spirit of social unity and cooperation, and in so doing prove its loyalty to the state it claimed to oppose.

Indeed, the editors of the party’s Hamburg publication, the Hamburger Echo, not only refused to publish correspondence critical of the authorities in relation to the epidemic; they voluntarily passed it on to the police. They also warned the police about actions by unemployed workers that they suspected, partly because they were organised by competing syndicalists, might become unruly.

The whole episode was largely seen as a dress rehearsal for 1914, when the party leadership more dramatically proved its loyalty to the state by betraying its principles and supporting the war effort at the outbreak of world war.

It took a major strike by dock workers in 1896 to renew the drive to action and win real reforms. The strike involved more than 16,000 port workers and lasted for nearly three months. Despite Social Democratic efforts to bring it to an end and its eventual defeat, the strike aroused enormous sympathy and led to real improvements in the living conditions of Hamburg’s poorest workers. The actions of mostly unorganised casual labourers had achieved what none of the organised political forces had been able to.

Nevertheless, as Evans points out, the transformation that the epidemic brought in the city’s official politics was reflected in the fact that all the city’s Reichstag seats were won by the Social Democrats in the 1893 national elections, and “they made such gains in local elections that in 1906 the city’s ruling Senate changed the voting qualifications to reduce the chances of a Social Democratic takeover”. Prior to this the party had enjoyed no official representation at all.

“The great cities of the industrial age”, Evans notes in his conclusion, “are so advanced in the complexity and fragility of their existence that even relatively small-scale disasters can plunge them into a state of chaos and helplessness”. Indeed, Hamburg was an advanced city that took pride in its independence and was widely considered modern and civilised. It was run by upstanding captains of industry who considered themselves superior to most. Yet thousands died when cholera arrived in 1892, not because the disease could not be prevented, but because the commercial interests that dominated the city administration resisted the disruption to business and trade that was required to prevent it.

This tragedy is playing out again, 130 years later. In societies much better placed to avoid such human suffering, hundreds of thousands are needlessly suffering and dying. In 1892, those responsible paid a high political price. Let’s hope they do again.