Much is made of Polish collusion with the Nazi extermination of Jews. Yet even the Israeli War Crimes Commission could identify only 7,000 collaborators out of a population of more than 20 million ethnic Poles. One survivor, Hanna Szper Cohen, said: “To this day I say – since Jews have bad feelings about Poles … we who survived, a small percentage though it be, none of us would have survived if in some moment he did not get help, usually without ulterior motives, from some Poles”.

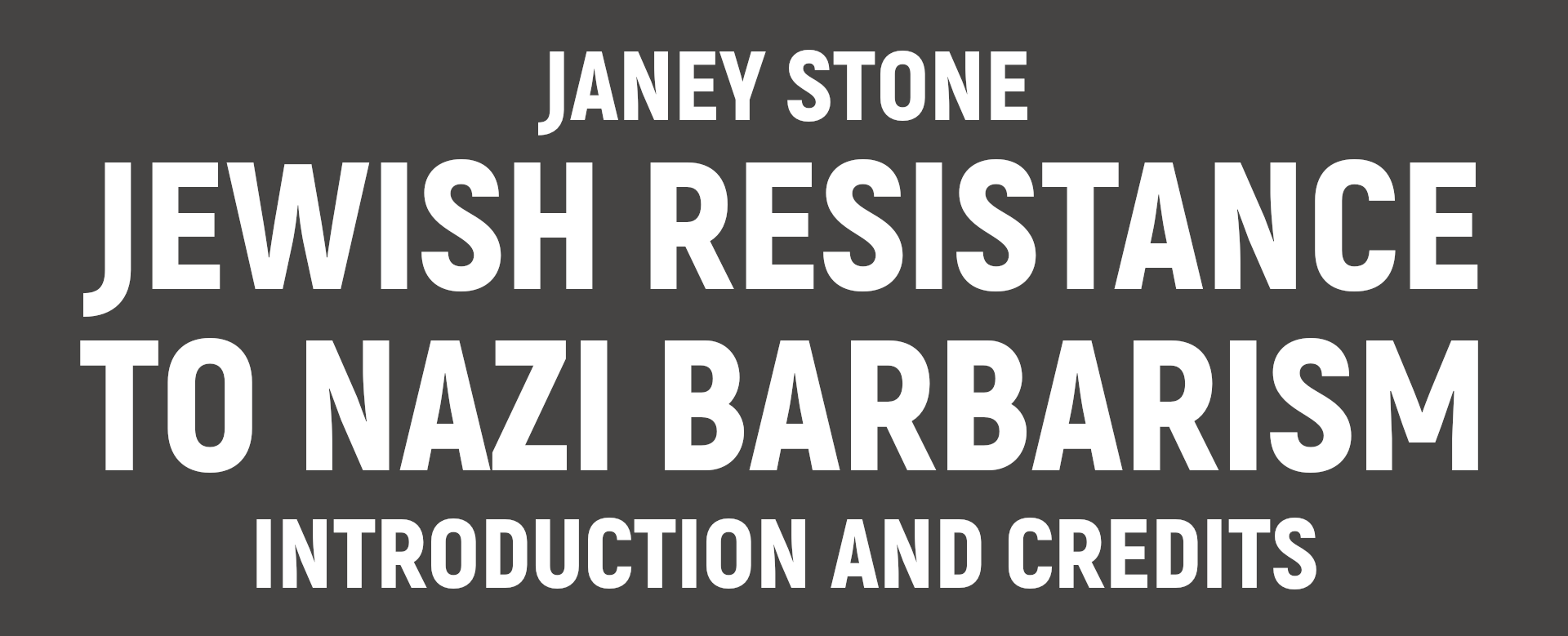

Poland had the most draconian penalties in occupied Europe for helping Jews in any way. In places like France and Germany, people attempting to help Jews faced severe consequences. But in Poland, not only the person but their whole family could be executed. Up to 50,000 Poles were executed for aiding Jews, and thousands more were arrested and sent to labour or concentration camps.

At the same time, Poles were themselves subject to genocidal attacks from the Nazis. For Hitler, all Poles were “more like animals than human beings”, and ethnic cleansing, known as “house cleaning”, displaced 900,000 people. More than 3 million non-Jewish Poles died. The Nazi food rationing provided 2,613 calories for Germans but 669 for Poles – barely above that allowed for Jews.

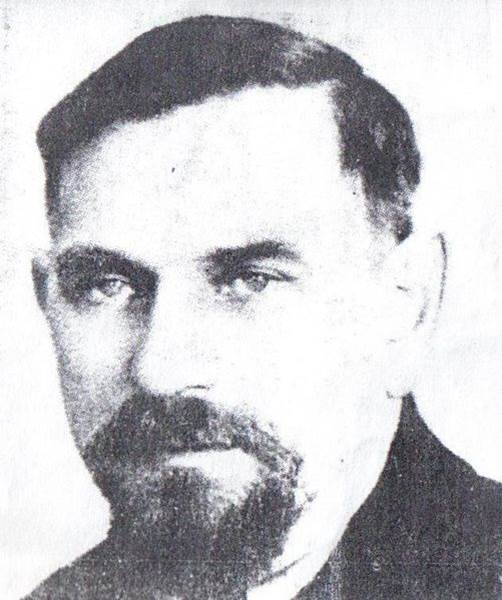

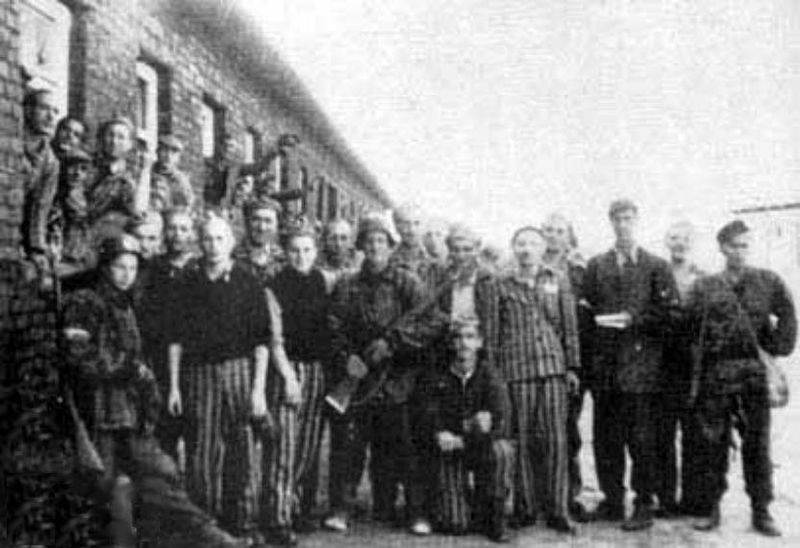

Help came in many forms and from both individuals and groups. Poland was the only country in occupied Europe with a secret organisation dedicated to helping Jews: the Council to Aid Jews (Rada Pomocy Żydom), known as Zegota, which helped approximately half of the Polish Jews who survived the war (thus more than 50,000).

Zegota was founded in September 1942 by Zofia Kossak-Snarrowzczucka, a Catholic activist, and Wanda Krahelska-Filipowicz (“Alinka”), a socialist. Members came from many of the left wing organisations that had opposed anti-Semitism in the 1930s, including the Polish Socialist Party, the Peasant Party and the Bund. But there were also Catholic activists and Polish nationalists, students, the scout association, the writers’ union, medical and social workers and activists in the Polish underground.

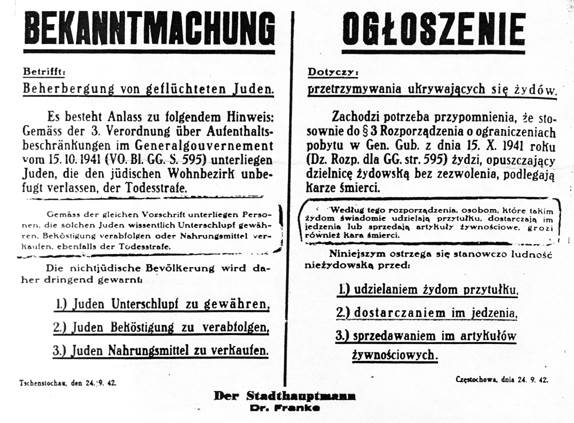

The first chairman, Julian Grobelny, had helped Jews before he joined Zegota and headed an underground cell composed mainly of socialist friends of the Bund. Because of his links to doctors and medical workers, he was able to hide people in quarantine. And due to his long involvement in trade unions, in particular his contacts with railway workers, he was able to arrange transport out of Warsaw.

Zegota’s headquarters was the home of a Polish socialist (Eugenia Wasowska) who had worked closely with the Bund. The organisation held “office hours” twice each week, at which time couriers went in and out. Despite the enormous number of people who knew its location, the headquarters was never raided by the Germans. One “branch office” was a fruit and vegetable kiosk operated by Ewa Brzuska, an old woman known to everybody as “Babcia” (Granny). Babcia hid papers and money under the sauerkraut and pickle barrels and always had sacks of potatoes ready to hide Jewish children.

The best known Zegota activist is Irene Sendler, head of the children’s division. A social worker and a socialist, she grew up with close links to the Jewish community and could speak Yiddish. Sendler had protested against anti-Semitism in the 1930s: she deliberately sat with Jews in segregated university lecture halls and was nearly expelled. She saved 2,500 Jewish children by smuggling them out of the Warsaw Ghetto, providing them with false documents and sheltering them in individual and group children’s homes outside the ghetto.

Zegota was not the only support group. What historian Gunnar Paulsson calls a “secret city” operated in Warsaw; between 70,000 and 90,000 people helped an estimated 28,000 Jews to live outside the ghetto.

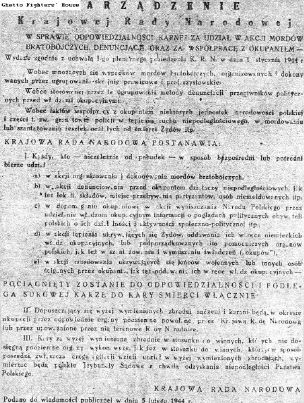

The divided stand on anti-Semitism of pre-war political currents continued during the war. While the right wing press contained anti-Semitic diatribes, the Polish Socialist Party and other left wing newspapers published information about atrocities and death camps, as did the organ of the Peasant Movement and those of the Catholic underground groups. Importantly, the Polish Underground State took a stand against anti-Semitism. It proclaimed laws against anti-Semitism and executed perpetrators, with details published in its underground newspapers. In early 1943, the Underground State’s official publication wrote that it viewed the murder of Jews with shock and horror and stated that Poles had a duty to help Jews, despite the death penalty awaiting anyone caught doing so. One major contribution of the Polish underground was its pivotal role in conveying news of Nazi extermination policy to the West.

SHOULD THE POLES HAVE DONE MORE?

We often hear people say that the Poles or other non-Jewish nationalities should have or could have done more to help the Jews. For instance, Epstein wrote: “If non-Jewish organisations with substantial influence and resources had done what they could to help the Jews, more Jews would have escaped and survived”. But she also pointed out that most Jews in Eastern Europe died when “the Germans were at the height of their power and when they were engaged in killing not only Jews but also Poles, Byelorussians, Ukrainians, and others”.

On this topic, Stewart Steven concluded: “Maybe Poland could have done more for its Jewish population, but then so could every country of occupied Europe. The record shows that the Poles did more than most”.

Paulsson reviewed a large range of available material and concluded that, despite the much harsher conditions, Warsaw’s Polish residents managed to support and conceal a similar percentage of Jews as residents of cities in safer, supposedly less anti-Semitic countries in Western Europe. The official count of Polish Righteous (people recorded at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Centre in Israel as having helped Jews) is 6,266. This is the highest count for any country.

Everyone acknowledges that the list is incomplete and no-one doubts more should be officially recognised. Any estimate is fraught with difficulties. Depending on which author is consulted, estimates of the number of Jews rescued by Poles vary from 100,000 up to 450,000, and the number of Poles involved in rescue as many as 3 million. Martin Gilbert noted: “Poles who risked their own lives to save the Jews were indeed the exception. But they could be found throughout Poland, in every town and village”. Paulsson suggested the following:

“How many people in Poland rescued Jews? Of those that meet Yad Vashem’s criteria – perhaps 100,000. Of those that offered minor forms of help – perhaps two or three times as many. Of those who were passively protective – undoubtedly the majority of the population.”

Indisputably, anti-Semitism was rife in Poland and throughout the Nazi-occupied areas, and many non-Jews thought only to save themselves, or denounced and betrayed Jews. This is an undeniable feature of the Second World War. But there were anti-Semites and betrayals in all countries and populations. Jews were even victims of denunciations and betrayal from within their own community. The Poles should not be singled out as an inherently anti-Semitic nationality.

On the contrary. The Jews who created underground organisations, who carried out uprisings, who escaped from the ghettos and concentration camps or who survived the war in hiding did so overwhelmingly with the help of non-Jews. Jewish survival and resistance went hand in glove with resistance and help from non-Jews.

‘LET THIS SONG GO LIKE A SIGNAL THROUGH THE YEARS’

Allied indifference to the fate of the Jews continued in the aftermath of the war. At the Nuremberg Trials, Jews were not even accorded the status of a distinct category. Arnold Paucker, a historian of Jewish resistance in Germany, comments on the fact that the historiography of the resistance in general, and Jews in particular, was a neglected subject prior to 1970. He traces this to the influence of the Cold War environment:

“The communist influence on the resistance was simply hard for many to stomach. Indeed, on this point we encounter a whole range of taboos and considerable self-censorship on the part of historians.”

In the Eastern bloc, Soviet policy (and subsequently the policy of the postwar Polish regime) was to emphasise the role of its own citizens without mentioning the specific experiences of Jews. A prime example is the report on the massacre of nearly 34,000 Jews at Babi Yar in the Ukraine in 1941. The draft report of 25 December 1943 noted:

“The Hitlerist bandits committed mass murder of the Jewish population. They announced that on September 29, 1941, all the Jews were required to arrive to the corner of Melnikov and Dokterev streets and bring their documents, money and valuables. The butchers marched them to Babi Yar, took away their belongings, then shot them.”

But the censored version, which appeared in February 1944, took away specific reference to Jews:

“The Hitlerist bandits brought thousands of civilians to the corner of Melnikov and Dokterev streets. The butchers marched them to Babi Yar, took away their belongings, then shot them.”

One reason why the role of the Poles in helping Jews is little known is because much of the information was suppressed by the postwar Soviet-backed regime.

Jewish historians also participated in the neglect of the subject of resistance and perpetuated the myth of “going like a sheep to the slaughter”. According to Arnold Paucker, Bruno Bettelheim “wrote on a number of occasions that German Jews had no backbone and persisted in a passive ghetto mentality”. And Raul Hilberg, a historian of the Holocaust, “constantly emphasised that, in the face of mass extermination, resistance [was] so minimal as to be practically insignificant”.

This type of argument serves Zionism, which holds that Jews are always outsiders and anti-Semitism can never be defeated. Theodore Herzl, the founder of Zionism, wrote in 1895 that he “recognised the emptiness and futility of efforts to ‘combat anti-Semitism’”. In 1925, Jacob Klatzkin, the co-editor of the Encyclopedia Judaica, wrote:

“If we do not admit the rightfulness of anti-Semitism, we deny the rightfulness of our own nationalism … Instead of establishing societies for defence against the anti-Semites, who want to reduce our rights, we should establish societies for defence against our friends who desire to defend our rights.”

This kind of attitude underlay their failure to play any significant role in the fight against anti-Semitism in Poland in the 1930s. Revisionist Zionists were planning a military invasion of Palestine and trained their youth group in the use of weapons. But they did not use their skills to join in the self-defence actions led by the Bund against attacks by anti-Semites. As one Revisionist leader put it:

“It is absolutely correct to say that only the Bund waged an organised fight against the anti-Semites. We did not consider we had to fight in Poland. We believed the way to ease the situation was to take the Jews out of Poland.”

But there is no way that Palestine could ever have been a solution for the poverty, oppression and anti-Semitism faced by the millions of European Jews. The Zionists themselves knew this and knew that their focus on Palestine meant leaving the bulk of the population to their fate. In fact, they deemed the bulk of the European Jewish population too tainted and not worth saving. Chaim Weizmann, leader of the World Zionist Organisation in the interwar years, said in 1937:

“The old ones will pass; they will bear their fate, or they will not. They were dust, economic and moral dust, in a cruel world … Two millions, and perhaps less … only a remnant shall survive. We have to accept it.”

Many Zionist functionaries who survived persisted in later years in their stand against underground activities, condemning them, for example, as “a series of childish and irresponsible antics that had achieved nothing other than to harm and further imperil the lives of … a community of hostages”. However, one leading Zionist, Nahum Goldman, did change his mind after the war:

“But in this context success was irrelevant. What matters in a situation of this sort is a people’s moral stance, its readiness to fight back instead of helplessly allowing itself to be massacred. We did not stand the test.”

In Bialystok and many other ghettos, Zionist youth did join and even provide leadership in the underground. Their actions are to be praised. But their actions were undertaken in spite of Zionist ideology, and their underground struggle had to be conducted mostly in opposition to the position taken by leading Zionists and the Jewish Councils. The Zionist youth groups in the ghettos separated themselves from adult organisations because of their unwillingness to follow what Epstein calls the older groups’ “cautious and conciliatory approach”. Lenni Brenner makes a critical point about Mordechai Anielewicz, the Zionist leader of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising:

“Mordechai Anielewicz’s apotheosis to historical immortality is entirely justified, and no criticism of his strategy should be construed as attempting to detract from the lustre of his name … However, the martyrdom of the 24-year-old Anielewicz can never absolve the Zionist movement of its pre-war failure to fight anti-Semitism – in Germany or in Poland – when there was still time.”

The real argument of the Zionists is not that resistance in this case was futile. Resistance was never part of their political agenda. As Brenner put it: “Those Jews who had resisted pre-war Polish anti-Semitism were the first to resist the Nazis. Those who had done nothing continued to do nothing”.

It also suits Zionist ideology to emphasise that the Jews were on their own. Many historians, Jewish and others, place great weight on how isolated and without help the Jews were. And no doubt this is how it must have felt to many. But the fact is that, aside from the small numbers who were able to pass themselves off as non-Jewish, almost all who did survive in Eastern Europe did so because they received help.

Epstein suggests that the reason the Minsk experience has received little recognition may be due to fact that the Warsaw Ghetto story, which emphasises Jews fighting virtually alone, suits Zionist myth making. The cooperation between Jews and non-Jews in Minsk is less suited to this:

“The forest/partisan model of resistance was predicated on the view that Jews and non-Jews had a common interest in fighting the Nazis, and it involved fostering such alliances … The problem is not that this form of resistance [military uprisings] has been so extensively examined, but that a memory of the Holocaust has been constructed in which other forms of resistance barely exist.”

She writes, “Every political current … regarded armed struggle … as more important than saving lives” and concludes that, had more underground organisations placed a higher value on escape, more Jews would have been saved. Saving lives depended more on external help than did a heroic but doomed uprising.

Zionists in general and Israel in particular have sought to appropriate the Warsaw Ghetto uprising to their own political purposes, to the extent of casting the establishment of the Jewish state as an extension of the uprising. But Edelman repudiated this. In a 2002 letter of solidarity to the Palestinians, he suggested that they were the real modern inheritors of the heroic Warsaw struggle.

Not only were the Jews supposedly completely alone – they were also supposedly surrounded by an immense sea of anti-Jewish hostility. There is no dispute that anti-Semitism was a significant and major trend in Poland and the region before the war and that groups from the local populations joined with the Nazis in committing atrocities. We have seen, however, the class nature of pre-war anti-Semitism. Furthermore, in the conditions of war, personal anti-Semitism was not necessarily determinant. Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, who was one of the instigators of Zegota, had anti-Semitic views, which she never repudiated. She nonetheless worked untiringly to assist Jews.

The leader of the Warsaw uprising in 1944, general Bor-Komorowski, had anti-Semitic tendencies. Nonetheless, the uprising released Jewish prisoners from Gesiowska concentration camp. The Polish Home Army and Underground State included people of all political persuasions, including anti-Semites. But their formal position leaves no doubt. Operating underground, they enacted laws against anti-Semitism and executed perpetrators.

There remains the question of why the Warsaw Ghetto was the only large ghetto in which the political factions were unified and the support of the bulk of the population was gained. This may be partly due to the fact that the ZOB ran the ghetto for three months before the uprising and therefore had a little time in which to win over the population. Furthermore, by this time, most of the children and older people had gone from the ghetto. Another pointer comes from Vladka Meed, a participant in the uprising:

“Jewish armed resistance … when it came, did not spring from a sudden impulse; it was not an act of personal courage on the part of a few individuals or organised groups: it was the culmination of Jewish defiance, defiance that had existed from the advent of the ghetto.”

In fact, defiance predated the advent of the ghetto. During the 1930s, the fight against the rising tide of anti-Semitism had involved Jews and non-Jews in mass struggle. This occurred in many cities and towns throughout Poland, but was centred in Warsaw. The alliances that were forged at that time continued through the Nazi occupation and underlay much of the network of help and support that the ghetto inhabitants received. The population that rose up in April 1943 had been mobilising on the streets only a few years earlier in 1938. The memory must still have been there.

Jews fought back against overwhelming odds and in the face of mass extermination. And they did not do this alone. Let Hersh Glik’s song, with which this article began, continue to be an inspiration to all of us.

We’ll have the morning sun to set our day aglow,

And all our yesterdays shall vanish with the foe,

And if the time is long before the sun appears,

Then let this song go like a signal through the years.